MIRAI: Intimate, Ambitious & Filled With Childlike Wonder

Alistair is a 25 year old writer based in Cambridge.…

Western discourse on anime features largely revolves around comparing where they rank in the animation canon alongside the efforts of Studio Ghibli. Naturally, this is an incredibly reductive manner in which to assess a diverse genre, the equivalent of comparing Sausage Party to Disney’s back catalogue of classics.

Director Mamoru Hosoda, after all, couldn’t even get hired by Ghibli after his concepts for Howl’s Moving Castle proved to be too surreal for the studio – and although his animations often deal with similar themes of childhood and family as Japan’s animation titans, his approach to storytelling is a completely different beast altogether.

A Time travel story rooted in the present

Take his latest film, Mirai, for example. On paper, you can understand why critics may lazily reach for the Ghibli comparisons; it’s a story about a young boy learning how to be a good brother to his newly born baby sister, and an accurate encapsulation of the stress of parenting two young, noisy children while maintaining a successful career. So far, so of a piece with Ghibli’s smaller scale coming-of-age dramas. But it’s his incorporation of the fantastical elements where Hosoda’s approach to the material becomes truly distinctive; with his latest, he shrugs off conventional narrative structure for a series of thematically related vignettes told from within the young protagonist’s imagination.

There are universal coming-of-age lessons to be gleaned from these tales, but they aren’t tethered into the humdrum reality of the rest of the film – and if your only connection to big screen anime is the gently magical worlds created by Ghibli, then the more surrealistic avenues Hosoda will lead you down are undeniably more suited to adventurous viewers.

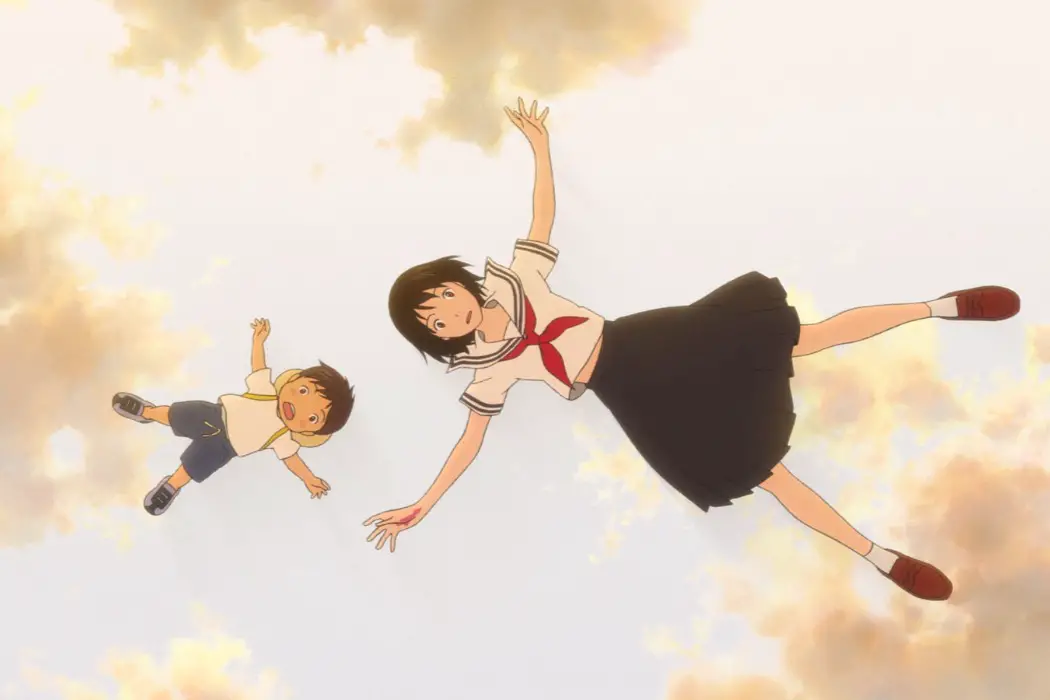

Four year old Kun is struggling to adapt to life with his new baby sister Mirai. His parents previously gave him their undivided attention, but now, he’s feeling a twinge of jealousy now that he isn’t the only one who needs to be cared for. When playing out in the garden one day, he discovers a whole host of characters, from an anthropomorphised version of the family dog to the grown-up teenager his sister will become, who give him lessons on how to adapt to his new responsibilities, and how to be a loving brother and son.

Even if it’s rooted entirely in its protagonist’s imagination (the film is ambiguous on this front), it still sees Hosoda return to his most recurrent concept: the passage of time. Only 2006’s The Girl Who Leapt Through Time has seen the director deal directly with the concept of time travel, but the vast majority of his films follow the coming-of-age process not through a revelatory moment in time, but as a pivotal era in one’s life.

Since the establishment of his studio Chizu in 2011, he’s explored this theme in increasingly unusual ways, but even in his earlier “gun for hire” animated gigs he’s managed to explore this concept. His debut big screen director credit, as co-director on Digimon: The Movie, spans the same number of years as his previous effort, the independently produced The Boy and the Beast – to him, fantastical narratives perfectly compliment coming-of-age tales, and help to illustrate the personal growth of a character over a number of years.

Surrealism rooted in the personal

Mirai is a peculiar movie on this front, as it manages to span back and forth through generations while leaving a foot firmly planted in the present. The film is increasingly structured as a series of vignettes connected by the overarching portrait of a family adjusting to a newborn, with each trip through history or further into the future deliberately weaved to compliment which life lesson Kun has to learn at any given moment. We see the future lives of characters, as well as the richly detailed childhoods of the adults, all vividly captured through an imaginative, childlike lens. It’s the first time Hosoda has shown us separate coming-of-age tales in a microcosm, focusing on important moments rather than encapsulating the essence of all the intervening years.

The film is inspired by Hosoda’s own children. His son was three years old when his daughter was born, and he built the surrealistic fantasy around an iteration of his own family dynamic. There are lots of character details that feel like personal touches imported from raising young children; from the painfully vivid temper tantrums at not getting any parental attention, to the messiness of a house covered in model train tracks, Hosoda grounds his film in a parental nightmare that feels universally relatable. The specifics may vary, but they are tangible enough to make any parent (or in my case, a person with significantly younger siblings) feel like the director had ripped a page out of their own stressed out life.

This is also Hosoda’s most ambitious production from a technical standpoint; although he mostly utilises traditional hand-drawn animation techniques, he incorporates CGI into his work here in a decidedly unsettling manner. In one of the later vignettes, Kun takes a train to a future Tokyo, but finds himself trapped in a high-tech train station akin to purgatory; the designs of the bizarre AI devices monitoring people, as well as the nightmarish train for “lost children”, have been crafted with different technology to the rest of the film. When standing next to traditional animation, it gives an uneasy quality; it’s oddly disturbing, especially in what is predominantly a charming rumination on family.

Mirai: Conclusion

Mirai may feel more like a series of thematically linked vignettes thrown together rather than a cohesive whole, but Mamoru Hosoda’s wondrous animation style, coupled with a deeply personal look at family dynamics, makes it hard to resist.

Mirai was released in the UK on November 2, and will be released in the US on November 29. All international release dates are here.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Alistair is a 25 year old writer based in Cambridge. He has been writing about film since the start of 2014, and in addition to Film Inquiry, regularly contributes to Gay Essential and The Digital Fix, with additional bylines in Film Stories, the BFI and Vague Visages. Because of his work for Film Inquiry, he is a recognised member of GALECA, the Gay & Lesbian Entertainment Critics' Association.