Milwaukee Film Fest Report: THE BODY REMEMBERS, GENESIS & RECORDER: THE MARION STOKES PROJECT

Midwesterner, movie lover, cinnamon enthusiast.

Below continues our coverage of the 2019 Milwaukee Film Festival, with reviews of The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open, Genesis and Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project.

The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open (Elle-Maija Tailfeathers and Kathleen Hepburn)

The Body Remembers When The World Broke Open, an English-language Canadian drama co-directed by Elle-Maija Tailfeathers and Kathleen Hepburn, is a (mostly) real-time account of a chance encounter between two women, Aila (Tailfeathers) and Rosie (Violet Nelson). Most simply put, in urban Canada (the film was shot in Vancouver), Aila sees the vulnerable Rosie, bleeding, bruised and bare-foot in the rain, escaping from her abusive boyfriend, and tries to get her some help — a change of clothes, some water and safe shelter.

The 105-minute film, shot on 16mm, consists of 14 long-takes stitched together, during which cinematographer Norm Li attaches himself to the two protagonists with over-the-shoulder shots and tight close-ups a la the Dardenne Brothers. The filmmakers are routinely obstinate enough to refuse turning the lens from Aila and Rosie, often denying their brief scene partners (i.e. the doctor and cabbie) a glance. There’s a thorough lack of visual exposition, which creates a sense of urgency and potential dread — Tailfeathers and Hepburn not letting us see others’ proximity or attitude allows the viewer to do the guessing work, sometimes expecting the worst.

But that sense mostly dissipates by the second act in favor of a tense struggle between the two women for intimacy, support and comfort. Tailfeathers, traditionally a documentary filmmaker, based the film off a real-life encounter she had, which she has called a direct confrontation of her privilege. Together, Aila and Rosie represent a diametric model of urban living: the former is a well-dressed Blackfoot-Sami woman living in a well-curated apartment with a loving partner, while the latter is a Kwakwaka’wakw woman who lives in her boyfriend’s mother’s house — she purposefully avoids him and speaks about not combing her hair in an attempt to avoid men that want to f*ck her.

There’s also the disparate relationship they each have toward motherhood. We first see Aila in a medical room getting an IUD, and when asked by Rosie whether she wants to have a child, she waffles. Rosie is pregnant with her abusive boyfriend’s baby. She seems to welcome motherhood. Whether it was her choice to have the baby isn’t revealed — it’s part of The Body Remembers’ beautiful ambiguity to suggest the possibility, or allow us to suggest the possibility — but it’s obviously not an ideal situation to be having a baby with a man who has kicked her pregnant belly, yelling about how it should have been aborted.

Tailfeathers and Hepburn use this class difference between them to gently suss out how that manifests in a position where someone like Aila is trying her best to help someone like Rosie. The second half of the film revolves around Aila’s attempt to get Rosie to a safe house, something Rosie is weary about — whether she wants to stay somewhere unfamiliar, whether she wants to leave her home, whether she wants to accept the help of others, etc.

For Another Gaze, Esme Hogeveen remarks on the complex situation we’re put in regarding this struggle for support, acceptance and help between the two due to the film’s purposeful lack of exposition:

“The viewer is placed in the uncomfortable position of pseudo-arbiter: we observe Rosie’s desire to be independent alongside her difficult position, as well as Áila’s own vulnerability, a force which underlies her desire to support Rosie. Without knowing the entirety of either woman’s situation, judgment seems impossible: throughout the film, would-be assessments about the characters’ decisions flip self-reflexively onto the viewer. Who are we to assess the righteousness of Áila’s advice, or what course of action would best serve Rosie? What is the relationship between receiving support and consenting to it? Rosie never asks Áila for help, at least not verbally, and in a few scenes she wryly queries Áila’s impulse to assist her.”

Alongside a lack of exposition, Tailfeathers and Hepburn are smart enough to avoid any significant resolution. Without revealing the ending, I’ll say it’s reasonable to find a glimmer of hope here, despite the fact that the film acknowledges the potential threat of abuse and its traumatic fallout. Whatever happens with Rosie after we last see her, 1) we can have hope that she’s in a better place than when we first found her, and 2) generally, there is so much hope in the concept that there are people and places, like the safe house, that are able to give people the support they need.

Genesis (Philippe Lesage)

French-Canadian filmmaker Philippe Lesage’s Genesis, a bifurcated narrative about young love that reveals itself, in the final 20 minutes, to be a triptych, is a steady, assured drama whose power has a strange occasion to sneak up on you.

Guillame is a loud-mouthed smart-aleck in the classroom and taciturn and confused outside of it, trying to suss out his homosexuality. His step-sister, Charlotte, is lost herself, toggling between two men who don’t fully appreciate her. Our quick glimpse of Felix, a younger boy, is less violent and dramatic than the other two — toward the end of summer camp, he and a girl camper realize their mutual fondness but, likewise lost but due to pre-pubescent immaturity, have no idea how to capitalize on it.

Lesage is in no hurry, and he’s often most captivating when he pulls us between romantic glances using deliberate pans from one side of a room to the other or allows his characters to dance in the club to electro-pop, sometimes without discernible action to move the plot along. This tone pairs well with his ability to focus in on poignant drama with staccato-like fashion, like during Guillame’s classroom confession, Charlotte’s tense wait in the car or Felix’s wordless hug.

Unfortunately, it’s when Lesage is actively trying to be explosive that he makes the largest missteps, most notably Guillame’s boarding hall fight and Charlotte’s sexual assault, which is so poorly handled. Because of the film’s content — beautiful young bourgeoisie in love — and Lesage’s trust in himself, I couldn’t resist connecting Genesis to Olivier Assayas’ Something in the Air and Mia Hansen-Love’s Goodbye, First Love. If Lesage could take one thing from either filmmaker, it might be their use of ellipses, which would’ve been a welcome tactic to avoid his momentary taste for the sensational.

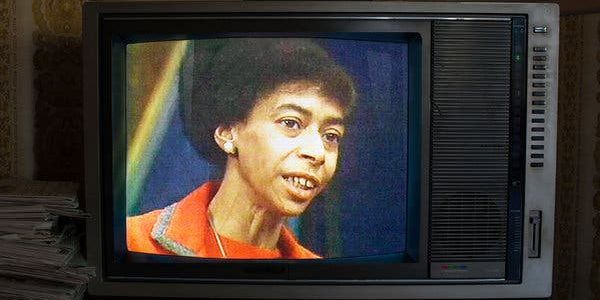

Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project (Matt Wolf)

The prospect of a documentary shining a light on Marion Stokes’ incredible project — recording television news broadcasts for 35 years — was very appealing. Her understanding of archiving something that 1) was broadcast to so many people, and that 2) was understood by most to be an ephemeral product is a lesson that still carries as much weight today.

Director Matt Wolf of Record: The Marion Stokes Project does well to connect Stokes’ recording obsession to her lifelong advocacy. He points out the Iran hostage crisis of the late 70s as the precipitating event of her taping interest. She had begun to notice the change in coverage from week to week that didn’t so much build off itself as reinvent itself ahistorically to position America as conveniently as possible. So, Stokes created a memory bank, or archive, that could exist against the idea that broadcast news was ephemeral, and thus, bendable to the will of stakeholders.

Unfortunately, Wolf’s interest in the project (which the title tags as its primary focus) is often sidetracked by his interest in investigating the drama of Stokes’ relationships — her reclusiveness, hardened temperament and how that affected many around her. This preoccupation is coupled with Wolf’s terribly bland aesthetic and narrative mechanics that seem to have been designed according to the biographical documentary style du jour out of inertia. The obvious comparison is Won’t You Be My Neighbor? and the cinema of Morgan Neville, generally. Besides style, Neville’s film is also, at its core, about television, but Neville is better able to weave the subject and the project.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.