The general understanding of mental illness has come a long way in the last century. Even in the last decade or so, we have seen the general consensus change, with specific terms making their way into popular vernacular and outdated attitudes uprooted for more progressive ones. However, there is still some way for us to go.

In this series, ‘Mental Illness in the Movies’, I’ll be delving into explicit and understated portrayals of mental illness, health, and wellness. There will be those movies that can be interpreted, metaphorically or otherwise, to be saying something about these same issues, and some whose deliberate attempts to portray these aspects I’ll be critiquing. For my part, I’m only one person out of a large spectrum of different experiences, so nothing I say is definitive, but an opportunity to open up discussion.

This time, we’re talking about Hereditary.

Hitting home

There’s a heavy weight of expectations when it comes to seeing Hereditary, as it is the latest film to find itself anointed ‘Scariest Horror of the Year’. I went into the film trying to put aside these expectations and see what I really thought of it, but came out a little confused. I wasn’t sure whether or not it was a great film, but I was absolutely certain that it’d had a significant, harrowing effect on me.

A common angle for horror films is to target specific, relatable fears, and take them to the next level. Bringing the fears we are often told are irrational to life is particularly disturbing for those who live, consciously or not, with that fear. For those that suffer from mental illness, director and writer Ari Aster taps into a specific fear – that of what we inherit, and what we pass on.

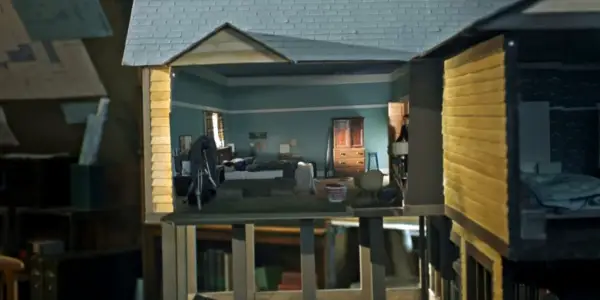

The movie’s opening shot is significant, both for my interpretation and the general claustrophobia it creates. We pull in on what looks to be the room of a dollhouse, until the camera enters the room, and the first scene begins. We soon learn that miniature houses and rooms like this are created by Annie (Toni Collette). She doesn’t imagine new scenarios, but returns to the past, re-creating often complex, traumatic, memories. As we enter their home this way, it appears that Hereditary has the same mindset.

We expect her to see the future in these, both as an artist who wants to move on from the difficulties she faced with her mother, and as an opportunity for jump scares (something similar to the most memorable part of 2011’s The Awakening). But there’s only the past there, and no premonitions.

‘Speak to someone’

It’s later learned that, under the guise of “going to the movies”, Annie is going to a support group. There, she is gently convinced to talk about herself, and she begins to list the many awful things that have happened to her family. She is half-laughing, nonchalant, awkwardly attempting to make these experiences of death and severe mental illness palatable in a room full of people she knows aren’t ready to deal with it.

No one has an answer to the problems she candidly shared, just more questions. Next time she arrives, she’s unable to even make it inside the building.

Annie’s reluctance to speak, and her shame after having spoken, comes from her fear at what would happen if she laid out her life for all to see. When it comes to mental illness, sharing your story can be incredibly difficult. ‘Just talk to someone,’ is an oft-repeated mantra, and for good reason, but for many the idea of making yourself vulnerable – for the listener to potentially recoil – seems impossible.

Joan (Ann Dowd) is the helpful Samaritan that extends the olive branch of communication, and has to push Annie before she lowers her defences. She may fear that she will only get hurt, or bring about more misery, if she shares her inner thoughts – and this is a fear that comes to fruition, as will some of her other deepest fears.

So what does Annie fear the most? Like many parents, it’s that her children will come to harm. This is clearly targeted in the death of her daughter Charlie, and the devastating effect this has on her son, Peter (Alex Wolff), but there is also another, more specific fear to consider: the fear of something she avoids at all cost, but is irrevocably bound to their family.

Inheriting the past

For those suffering from mental illness, there is often fear, frustration and many other uncomfortable emotions to go through when you think about how conditions are often passed on from parents to children. While Hereditary‘s scares and building dread work for viewers of all sorts, for those with mental illness and disorders, it taps into the fear that you and your kin are trapped by genetic misfortune – and displays how this can disrupt family life.

Though it’s by no means a portrayal of the ins-and-outs of a family who all share this weight, Hereditary does zero in on one frightening prospect: the horror of being stuck in a cycle, trapped on a path of suffering by those that came before you, and terrified that you may give the same illness over to the next generation.

It’s an uncomfortable and dark thought to dwell on, even for those who find themselves swaying into dark thoughts on the regular, so it’s not one that often makes its way into film and television (though both Bojack Horseman and The Sopranos do offer rare glimpses into the anxieties of passing on mental illness).

The miniature house from the opening shot, seen from the outside, portrays traumatic moments and difficult relationships in a much more manageable way. This is the perspective those suffering from the likes of depression can seek and often find in moments of clarity of healthy living. Annie looks for this perspective in her art, but – as the opening shows – we are in the rooms of this house, and we don’t leave.

Rather than isolating the traumas of the past, Annie is destined to repeat them – either literally as with the fire and paint thinner, or in spirit – as the past comes back to ruin the life she has created in the present. The actions of her mother during her life were too difficult to face dead-on, but by ignoring and suppressing them, they come out in her work – and eventually come back to life in full force.

Both Charlie (Milly Shapiro) and Peter are going through their own specific problems, both for their ages and their own forms of mental illness. Neither are similar enough to their mother to understand her, or for her to completely understand them.

Peter misunderstands, Charlie rejects, and Steve (Gabriel Byrne) – the most neurotypical – is patient, but lacks the insight to truly empathise, and ultimately can’t discern the fantasy from the reality. Even the most well-meaning can often find it difficult to grasp when someone who suffers from these things needs help or not. The deepest fear is that the subsequent alienation and misunderstandings can lead to something even worse.

Navigating a family with mental issues is never easy, and Hereditary dives into our worst fears of it – that the disruption will escalate and ruin the lives we build, parents’ fear that they have doomed their children, children’s fear that they are on a path they can’t escape. Taking a step back and seeing these scenes as miniatures gives us room to interpret and separate, but once inside, things are far harder to parse.

Hereditary: Concluding thoughts

Any comparison between this setup and your own family life or anxieties doesn’t have to be that close for it to hit home. Whatever effects mental illness or traumas may have had on your life, you’re bound to find your outlook veering into the bleak and intense at times, which alone makes this elevated portrayal relatable.

It’s perfectly possible that the mental health of the characters in this movie are simply reactionary to a strange series of supernatural events, there as background detail or the usual plot misdirection – however, this interpretation works both ways, for me, regardless of the intent of Ari Aster and co. And however unsettling or shocking it can be in the moment, there’s something cathartic about confronting these fears in the safe space of the cinema.

What are your thoughts?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.