Melbourne Documentary Film Festival 2020: Interview with Posy Dixon, Director of Keyboard Fantasies

Alex is a 28 year-old West Australian who has a…

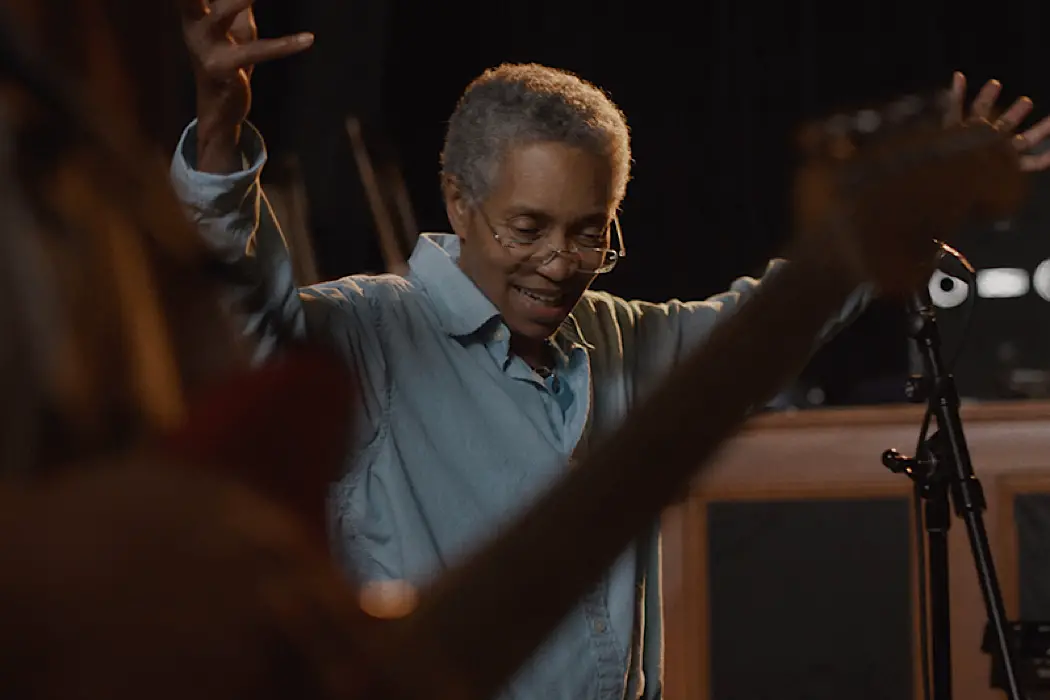

From the opening moments of Posy Dixon’s Keyboard Fantasies, the welcoming and warm nature of the titular musician, Beverly Glenn-Copeland, is instantly noticeable; guiding the camera crew into his personal work-station, the 76-year old Canadian-based musician unveils the “secret” cupboard which holds the remnants of ‘Keyboard Fantasies’, his cult 1986 electronic album that was only originally self-distributed via cassette tape. This heartwarming tribute picks up just after Glenn-Copeland’s late-career resurgence, which came about when a Japanese audiophile known contacted the singer-songwriter to send him copies of the album in 2015 which he then sold immediately, leading to a vinyl re-issue and a series of international tours (which were recently rescheduled due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

Similar to Iván Castell’s Synthwave chronicle, Dixon doesn’t focus on the technicalities of the music, but rather the person behind the keyboard; delivered within a succinct, immaculate 60-minute package, Keyboard Fantasies doesn’t condense the different facets of Glenn-Copeland’s prolific life into a generic, hagiographic illumination – this is a story of a singular artist that feels like a natural extension of his considerably influential body of work.

Ahead of the film’s screening at this year’s Melbourne Documentary Film Festival, I had the chance to talk with the film’s director, Posy Dixon, about her documentary, the effect of Beverly Glenn-Copeland’s music, the film’s aesthetics and how it was to Kickstart the project.

This is Alex Lines for Film Inquiry. Were you aware of Beverly Glenn-Copeland’s work before making the documentary?

Yes, I was. Like many, I heard Keyboard Fantasies and developed a mild obsession with the record, which led to an internet wormhole excavating everything I could about the artist. This led me to a recording of Glenn talking at the Montreal Red Bull Music Academy. I stalked him down on Facebook, did a reach out and a few Skype calls later we were buds for life and it went from there.

For those who may be unaware, would you be able to explain the significance of the album Keyboard Fantasies, as a pioneering work of electronic music?

Glenn wrote Keyboard Fantasies back in 1986 when he was living as a woman in rural Ontario, making music under the name Beverly Glenn-Copeland. He had recently discovered computers and the power of synthesised music and wrote this stunning record in short frenzy of creativity on a Yamaha DX7 and a Roland TR-707. He self- released it on cassette selling just a handful of copies.

Fast forward thirty years and somehow one of those cassette tapes made it’s way into the hands of a rare record collector in Japan who started the ball rolling on sharing the gem with the world. In the past three years the record has be re-issued several times and has achieved what I think would be safe to say a cult status among a rapidly expanding community of fans.

Why do you think Glenn-Copeland’s music, Keyboard Fantasies in particular, has connected with so many people on an international level?

It’s funny, Dan Snaith (Caribou) said this thing about the record, that when he heard it, he felt like he’d known the music his whole life. There’s something timeless and placeless about the melodies that seem to connect universally. Glenn compares himself to a radio that receives music and translates it to share with the world – I guess when Keyboard Fantasies came through the Cosmos was pumping out a real crowd-pleaser.

How was the Kickstarter process for bringing this project to life?

A big old pile of work, but it did the trick. When we were fundraising Glenn’s profile was significantly more on the down-lo then it is now, so we were literally tracking down individual fans and asking them if they’d be so kind as to support the project. I felt weird about asking people for money, but we had a deadline set by Glenn’s European tour so we needed to raise a little pocket of cash fast. One thing I will say is that having a portion of the film crowd-funded certainly puts the pressure on – you really don’t want to accept money from strangers and make a doozy of it.

One interesting choice I noticed was that, outside of the candid backstage footage of Indigo Rising, everyone who isn’t Glenn-Copeland is presented purely through audio – as opposed to a row of talking heads like most documentaries – can you talk about this decision and how you went about forming the film’s structure?

It was a stylistic choice really. I wanted the film to feel like an audiovisual tapestry of Glenn’s life, so you get the experience of travelling through time with him, from the 1940s to the present day. Talking heads would have burst that bubble.

From the first moment we meet Glenn-Copeland in the film, there’s an immediate warmness to him, and I feel like this extends to the film’s aesthetics – softly lit with warm textures – was this the type of emotion you wanted to translate aesthetically?

Definitely. Glenn is one of the most engaging people I’ve ever met. When he’s talking to you, it’s like you’re the only person in the world – which I believe comes from years of work as a practising Buddhist. I wanted that level of intimacy to be shared with the audience, so didn’t want theatrical lighting or complicated framing. I wanted it to feel like you were having a long cosy chat with a really good friend in their front room. Which is I guess, what I was enjoying at the time.

What was the process of translating Glenn-Copeland’s music into visuals – especially in regards to the opening credits and intertitles?

Those dreamy coloured trees were created in collaboration with two very special artist friends, Whitney Conti and Peter Wynne-Wilson. Pete is a light engineer who worked with Pink Floyd in the ’70s creating all their analogue live visual effects. Whitney be-friended Pete and got access to a huge warehouse full of technicolour toys, where she found these stunning dichroic glass plates that Pete had made way back when.

I’d seen some stills she had taken with them, and immediately knew I wanted to use them for Keyboard Fantasies. I spent a bit of time finding the most Canadian-looking forest on the outskirts of London and we were set to go. The icing on the cake came in the form of a few reels of 35mm film – one of our DOP’s Morgan Spencer has just got off best-boying on Star Wars and they donated their left-over film stock.

How has it been touring this film during such an unpredictable time?

Well, you know of course it’s been a massive bummer not to be able to travel to film festivals and enjoy Keyboard Fantasies with a live audience, and of course Glenn, but I count myself as super lucky as we managed to have premiers in London and New York before the Virus emerged. So we got to have our ‘moment’ with Glenn and our family and friends.

I’ve been really impressed by how quickly the festival circuit has gone digital – there’s a whole bunch of film enthusiasts around the World working their butts off keeping the independent film circuit on-track and I’m really grateful for that.

Film Inquiry thanks Posy Dixon for taking the time to talk with us.

Keyboard Fantasies will be screening at The Melbourne Documentary Film Festival from June 30th until July 15th, information about ticket prices and the full program is available here: http://mdff.org.au/

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.