The information age has ushered in an era of unprecedented opportunity for learning, with incalculable data available to us at any given moment. On the flipside are the negative byproducts of such privileges, such as an ever-present cognitive overload, a condition that has become something of a daily reality for anyone trying to prevent being left behind by modernity. Rifts between the throngs trying to “make it big” and the successful who embody that goal create multiple opportunities for those with the right combination of luck and tenacity. But success is a double-edged sword, and those who profit by perpetrating its rosy image continually present new doors that promise to help the average citizen reach that elusive goal, while contradictorily ensuring most of those doors remain tightly closed.

In 1987, the McDonald’s Corporation implemented for the first time a promotion that would prove enormously successful in increasing sales and improving brand recognition. The Monopoly game became as commonly known as the Marlboro Man, and McDonald’s ran it over and over again for decades.

Still, as with most marketing campaigns, the only real winner is the house, McDonald’s in this case, who consistently saw sales increase as much as 40% whenever the game was run, according to Simon Marketing employee Richard White, one of many interviewees in McMillions. The few million it costs to run the promotion and award the prizes is less than a pittance compared to a 40% increase in an average yearly revenue between ten and twenty billion dollars. The game was presented as a quick and easy way to score big prizes or cash money, finding that sweet spot below “too good to be true” and above “too difficult to be worth it,” and the financially hungry public fully bought in to the promise of tantalizingly easy-to-obtain material wealth.

Amongst all of the advertising campaigns and slogans, the political messages vying for our attention, and the wealth of information available on the internet, fraudsters often hide in plain sight, hidden from view only by the sheer volume of stimuli ever-present in daily life. The layperson is often left to wonder and fear just how much corruption runs along the threads connecting the various corporate giants. That corruption is the subject of HBO’s newest documentary, McMillions, a candid look into the rigging of a single marketing campaign, but also providing a window into how the corporate corruption we fear is perpetuated.

McMillions

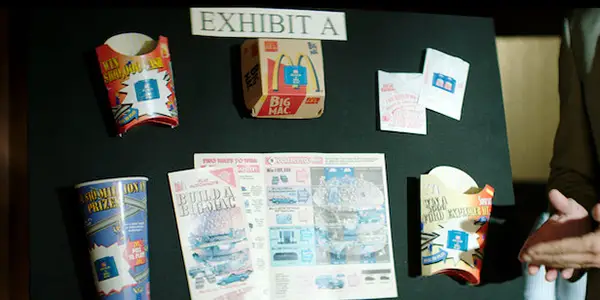

Over six episodes, the HBO documentary miniseries McMillions depicts a fraud of epic proportions, the ultimate meaning of which is that between 1989 and 2001, “there were almost no legitimate winners of the high-value game pieces.” (documentary interviewee Doug Mathews, FBI agent) In the early days of the first contest, Jerry Jacobson, a security staff member at Simon Marketing (the company contracted by McDonald’s to run the Monopoly game), received a small envelope that had been sent to him by mistake. The envelope contained security stickers, the sealing of which served as proof that the winning game pieces had remained untouched. Through some minimal effort and a touch of shady maneuvering, he was able to obtain a couple of extra necessary pieces of information, such as a briefcase combination, and then use his position to steal the high-value pieces, replacing the torn security stickers with those he had received.

For years, he would steal the winning pieces, and rope people into claiming the prizes in return for a share of the profits. Over time, it became something of a pyramid, with “Uncle Jerry” at the top, providing pieces to various distributors, who in turn would give the pieces to people who would claim the winnings. Eventually, someone blew the whistle, and the FBI became involved. After an investigation, the participants were arrested and given various sentences, including jail time and/or restitution fees. Jacobson himself was given three years, in addition to restitution fees.

The Documentary Craft

McMillions‘ opening shot is a bird’s-eye view of a small town nestled into a thick woodland. It’s a powerful message of contradiction: the urbanization seems to cut through the trees, forcing themselves into place, a forced, rigid order shoving aside the beautiful, natural chaos. Following the opening credits, four simple shots perfectly set the stage: a beautiful beach gives way to a pristine apartment highrise, which then surrenders to a dilapidated apartment lowrise, and finally, to the swampland seen from above.

This theme of dichotomy is ever-present throughout McMillions. To name a few examples: FBI agents are depicted eating McDonald’s food while investing the McDonald’s fraud; characters are depicted in one episode as “generous” and “kind,” and then in the next episode as “evil” and “cruel;” the difference between legal counsel arguing for the law as opposed to arguing for the rules of a sweepstakes game; and of course, as we’ll discuss later, the difference between the abilities of the financially affluent and the financially dependent.

The choices made behind the camera furthered this idea of difference, of separation. The camera is static during interviews, but consistently tracking during the dramatized sequences, each one rife with stylistic choices. A thick black line suggesting comic book panels makes multiple appearances throughout the dramatized sequences, again suggesting the idea of separation. These lines are really quite a brilliant device: in addition to the thematic idea of separation, they also invoke the feeling of a game by making you think of cards or stickers or places on a board. It’s not heavy-handed, but subtle, and so good. A perfect example of how to fulfill a creative thematic vision.

With interviews, the currently-in-vogue-for-documentaries triple camera setup is heavily used: one camera set up as a traditional medium shot with standard lead room used the most frequently, a full shot with heavy lead room most commonly used in lighthearted moments, such as the interviewee telling a humorous anecdote, and the off-putting Closeup, set to provide very little lead room, placing the speaker on the “wrong” or “uncomfortable” side of the frame, and mostly used during tense moments in the narrative, or when a main point of story is being delivered.

While there is much to be celebrated in the craft of McMillions, there are also many weaknesses. The first and most obvious of which is consistent with most modern documentaries, thanks to the currently popular style for the art form. You always wonder just how accurate these documentaries are. It’s so easy to cut and doctor things in a certain way in order to elicit a certain response from the viewer, and make it look as though it wasn’t doctored at all.

Obviously such theft and rigging of these games is a terrible thing (despite the fact that the moguls behind financing such games are often guilty of far worse), but you wonder just how “evil” or “good” these individuals are, beyond the way they are portrayed. Modern documentaries seem more concerned with duping viewers into buying a certain idea, invoking a feeling more in line with reality TV than with the search for truth pervading the great documentaries in film history, such as The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On, for example.

McMillions seems fully invested in establishing itself among these modern examples of the documentary form. One of many examples is its interview staging. Everything is so incredibly unnatural, set up to look as “documentary” as possible, striving for a feeling of perfection that betrays the series’ supposed attempt to portray the truth. Truth is always messy, and the creators of McMillions clearly chose presentation over content. Of course, such is the standard in modern documentaries, so to name McMillions as the only guilty party would be unfair.

The Deeper Message

According to annual sales reports from the company, McDonald’s was making at least $25 billion in sales per year during the period this fraud was taking place, before profit increases thanks to the Monopoly game, which brought in an extra $15 billion. It takes money to make money, and once a company has reached a certain undrawn “line” in capital a series of interesting things happen, not the least of which is entitlement (supposedly) to legal counsel whose singular purpose is to find legal justification for that company’s money-making schemes. Let’s call this lawyer Bob.

The dictionary definition of fraud is: “wrongful or criminal deception intended to result in financial or personal gain.” The keywords in that definition are right at the beginning: “wrongful or criminal.” These are the words that Bob spends all his time working with, because if the deception was intended to result in financial gain, but it was not wrongful or criminal, then his client can do basically anything they’d like. If he can convince the powers that be that the words “wrongful” and “criminal” are fluid when it comes to his powerful corporate client, he can push the legal envelope and help his employer make that extra money using a huge variety of highly questionable schemes, only a few of which are ever made known to the public at large.

Eventually, the legal system itself becomes beholden to those who can pay for its loyalty. A simple example of this can be seen in the words of FBI Agent Doug Astralaga, at about the 11:40 mark of episode 3, wherein he says, speaking of the “mission” to protect McDonald’s from losing money or reputation due to the game pieces scam: “We knew the mission we were trying to accomplish was a noble one and a good one.” Really? It’s a noble mission to exclusively protect those who can most easily pay for protection? This argument boils down to a defense of the capitalist status quo, but in reality, nobility is very much the opposite. To become “Robin Hood” may be the only truly “noble” path left.

These legal advantages provided by capitalism and its champions are, of course, only provided to those who can pay for it. Enter the real victims of this scheme: those who were roped into claiming the winning game pieces. The best example of this is Gloria Brown, one of the winners introduced in episode 3. A single mother of color, wanting a better life, agrees in desperation to the scheme. Her story provides a perfect example of the destruction resulting from corporate greed behind games like McDonald’s Monopoly.

The desperation of average people who see in this game EXACTLY what the ads promise: a way out. These games and their advertising are only effective because inherent within the very reason behind their creation is the understanding that people want something better. If, suddenly, something comes along that says “I guarantee you will win, and all you have to do is such and such,” OBVIOUSLY you would take it.

FBI Agent Doug Mathews tries to argue that the real victims in this case were “all the people that participated in this contest and thought that it was legitimate.” Yes. Exactly right. And what does that mean? This contest, and many others like it, as well as advertising schemes, etc., are set up to lure people into spending money for a “chance” of winning. We are cognitively predisposed to have a desire for that type of risk-taking, and McDonalds is but one of many companies knowingly taking advantage.

An obvious example is the mobile gaming industry: the entire system is built on this concept of “pay more to win more” but in the end, it’s usually just chance. How is that not “wrongful or criminal deception intended to result in financial or personal gain,” again, the very definition of fraud? In the end, the ultimate message of McMillions is one the 99% already know all too well: the 1% are not beholden to such petty inconveniences as “morality” and “law.” They play by their own rules, and the rest of us are forced to pay for the consequences.

Conclusion

In episode 3, at about 51:05, Mark Deveruax, the principal litigation attorney representing the case, says the following: “Human nature makes us do different things. People want to justify what they did or why they did it. So they can live with themselves. Everyone. Everyone watching this show cannot stand in front of a mirror and look at themselves in the eye and say they’ve never done something that they wish they could correct and take back.”

Yes, but for most of us, including some of those winners, what we’ve done has been hurtful to only ourselves, or a small number of people. While those who perpetuate this game and games like it are guilty of far worse: the preservation of a status quo that disadvantages millions in order to stuff their own coffers. That is the real McMillions.

Who do you think was the real victim in the McDonald’s Monopoly scam? Let us know your thoughts in the comments below!

McMillions aired in February and March of 2020 on HBO.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8zHfScOWO8

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.