THE MATRIX RESURRECTIONS: Looking Back & Taking Back What’s Theirs

Soham Gadre is a writer/filmmaker in the Washington D.C. area.…

In 2021, two filmmakers released movies that self-examined the artistic legacy of a film series and its creator. For Hideaki Anno, completing the Rebuild of Evangelion with Evangelion 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon A Time meant redefining what he created and re-examining a new path forward for his cipher, Shinji. For Lana Wachowski, the legacy of The Matrix branched and stemmed over this very-online 21st century into increasingly circuitous theories, philosophies, and political ideologies. While I don’t think it was ever possible for The Matrix Resurrections to put any of the worms back in the can so to speak, nor do I think the Wachowskis are concerned with “what it all means”, it was still a moment and opportunity for the creators to say their piece about their film and to regain, reclaim, and re-direct its ideas. What makes the movie a successful addition to the series, and more importantly, an interesting one is that the re-direction went directly inward – literally back into the Matrix.

Drowning Out the Noise

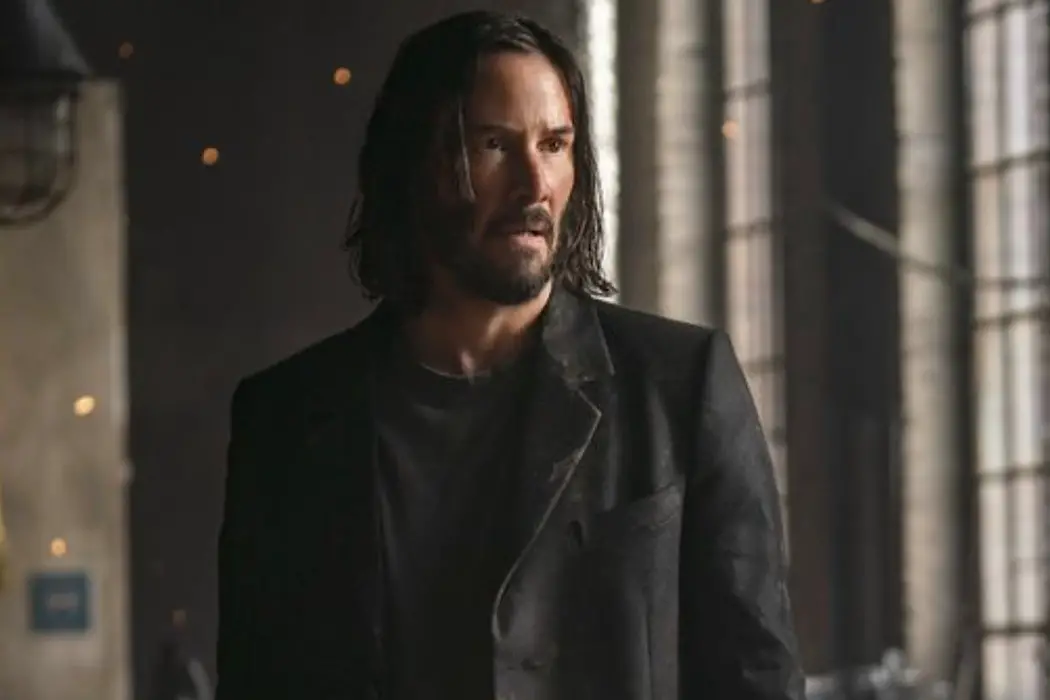

Lana Wachowski sets the tone for the entire film when Keanu Reeves, playing Thomas Anderson, a now-successful game designer of the Matrix game series, is tasked with making another one by his snarky and money-minded boss. The entire conversation is so blatantly direct, calling out Warner Brothers by name, it simulated the feeling of the movie, its characters, its world, gaining consciousness of the audience watching it. The sequences that follow dive straight into this self-awareness. A montage of colleagues at the video game company brainstorm what The Matrix means for them… guns, cool guys with glasses, political awakening, revolution, a trans allegory, everything we’ve seen and heard online and in film criticism over the past 17 years is poured out onto the screen in rapid succession. Meanwhile, Thomas Anderson floats through his life. He wakes up, takes a blue-colored pill, gets coffee, writes some code, visits a shop, and sits contemplatively in a bathtub. “White Rabbit” by Jefferson Airplane plays over the montage.

The deliberate and obvious symbolism in the movie showcases a clear distaste with “interpretation”, instead, bringing everything to the surface and slapping it across the screen in a jumble and leaving it there to hang. When any supposed “new” character or persona arrives, the movie cuts to show who they were in the previous films. Morpheus (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) and Smith (Jonathan Groff) are given new visages and personalities while still making no mistake as to who their originals are. A new character named “Bugs” has a rabbit tattoo and is the one who leads Thomas Anderson back down to “Wonderland”. There’s nothing to misinterpret. All the cards are on the table in this film and if we choose to bend them to our self-validating beliefs, well, that’s solely on us.

A New Look

This is also a sequel that has embraced in showing how the times, particularly for Hollywood and tech, have changed. The movie’s visual canvas illustrates a major shift in American aesthetics since the turn of the century. The open, clear, bleached sheen of this film is vastly different from previous iterations which reflected the grimy punk neo-noir decors of a late-GenX pre-tech-boom aesthetic (also reflected in other sci-fi of the time, ExistenZ, Equilibrium, Dark City, etc.). This one has the artificial trappings of a Silicon Valley open-floor workspace – bold candy colors, brilliant whites, shiny ornaments, a pristinely well-lit coffee shop called Simulatte that serves picture-perfect cappuccinos… it plays up the hollow but sleek over-aestheticization of our modern world to the nth degree. Wachowski embraces digital imagery’s possibility to create new images that form a distinct style rather than trying to revert it back to (poorly) imitating celluloid.

The action sequences have an added panache, especially with the slow-motion, but the choreography (this time without Yuen Woo-ping) can’t escape the post-Jason Bourne era style where physical impact is manufactured through rapid cuts. It’s a disjointed and often-times muddled coagulation of movements that lack the balletic verve of the previous movies, where every hand hitting an arm or foot kicking a chest is really felt. While the old action set pieces aren’t quite matched, Resurrections ends up being the most inventive Matrix movie since the first one because of what happens outside the action. The exposition in this film, unlike the previous sequels, is much more interesting.

Words Don’t Mean a Thing

The film flips many late-Hollywood trends but namely, it toggles definitions of the Matrix within the current culture of nostalgia and being online. This is a movie loaded with the type of terminology you see being used flippantly on social media – red pill, binaries, trauma, triggered, etc – where it has lost meaning through its endless variations and re-appropriations from different people. Most of this is siphoned through The Analyst (Neil Patrick Harris), a semi-successor or equal prototype of The Architect from The Matrix Reloaded, who throws loaded buzzwords like “triggered” and “trauma” at Anderson to convince him that his recollections and experiences with the Matrix are just hallucinations or some form of PTSD.

Emily VanderWeff explains in her piece at Vox that “The Analyst’s invocation of trauma is… a strike against trauma as a cheap storytelling device”. In the same way that nostalgia and red-pill have become ways for people to build lore and alternative cultural realities for themselves in their internet bubbles, The Analyst’s main function in Resurrection is to use therapy as a story to keep Thomas Anderson distracted and away from the actual thing that would help him – love.

Conclusion

This is a curious and fascinating sequel, one which is completely aware of its own existence but also confused about why it exists. In the end, the meta-narrative, yet another storytelling device just like The Analyst’s diatribes, stops to get back to root of this series. The deep bonds between Neo and Trinity (Carrie-Ann Moss) in the movie are what serve as the fulcrum to tilting this film back in line with its core, sincere conceit that love transcends dimensions. It’s the one lens from which Wachowski makes the case that the Matrix series can keep going. It’s the one through-line of this series that shatters the illusion of the Matrix and all manners of its cultural misinterpretation.

The Matrix Resurrections is currently in theaters and streaming on HBO Max

What did you think? How does the sequel compare to the others? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Soham Gadre is a writer/filmmaker in the Washington D.C. area. He has written for Hyperallergic, MUBI Notebook, Popula, Vague Visages, and Bustle among others. He also works full-time for an environmental non-profit and is a screener for the Environmental Film Festival. Outside of film, he is a Chicago Bulls fan and frequenter of gastropubs.