Butchering the God Butcher: Why Marvel Should Fire Taika Waititi

Brian Walter is a college professor by day and a…

Taika Waititi is a sly, funny, gifted filmmaker. He makes artful movies that can erase, with remarkable ease, the boundaries between “fantasy” and “reality,” imbuing the magical and the impossible with an unlikely naturalism while, at the same time, enlivening the everyday with humor and heart. He’s a court jester whose delightful wit conjures everyone from Oscar Wilde to Vladimir Nabokov, from Charlie Chaplin to Ernst Lubitsch to Alfred Hitchc*ck. He’s a gift to filmgoers and to Hollywood itself.

But Marvel Studios needs to fire him.

Not from the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) altogether, because there are plenty of storylines and characters that his rich sense of humor could serve superbly. (Near the end of this article, in fact, I’m going to suggest a budding new MCU property tailor-made for him.) But the MCU should remove him from the Thor franchise, which he took down a dark path in Ragnarok and largely destroyed in Love and Thunder.

“Dark path” should be read ironically here. Both of Waititi’s Thor movies take full advantage of star Chris Hemsworth’s easy command of the screen to spin out improbably funny, affirming versions of what were, in their day, two of Marvel’s darkest, most iconoclastic storylines. But that’s the problem. For all of their irresistible elements (especially Cate Blanchett’s show-stopping turn as Hela, the Norse goddess of death, in Ragnarok), the films make a mockery of the tragedies on which they’re based.

This is not a sacred cow sin, where ardent fans who insist on slavish fidelity are angry that their favorite storylines were (inevitably) modified for the screen. It’s a sensibility problem. Waititi is a brilliant natural comedian, clear-eyed, to be sure, but fundamentally a relationship-broker and community builder. No matter how dark and subversive various elements may be, his movies finally work to bring people together, basking in wit, warmth, and generosity.

The Mythos of Winter

In sharp contrast, Thor and the stories of the Norse pantheon are deeply and fundamentally tragic. Tragedy, as everyone from Aristotle to Nietzsche to Northrop Frye has pointed out, works to isolate its heroes, bringing them to a great height only to send them plunging down in ruin, cut off by their own pride and ambition from all sources of social comfort. The climactic loading of the tragic stage with corpses ends with the tragic hero completing the body count. Frye usefully names tragedy the mythos of winter, an image of the human condition at its coldest and bleakest, its inspirations achieved only by a devastating loss.

But Waititi is a comedian, and comedy is the mythos of spring. It renews life after the deadness of winter and opens up a new hope and the possibility of new joy, usually embodied in a new relationship that would have been impossible earlier in the story. When Waititi has Thor (spoiler alert) make pancakes for Gorr’s daughter at the end of Love and Thunder in a cozy middle-class idyll, the world is made whole and ready for new life again. In a story that features the ravages of terminal cancer and a rage-fueled vendetta against the very idea of the divine, Waititi reaches for a comedic ending, a reassurance that Thor has his replacement for the lost love of his life, so the series can proceed.

Waititi’s domesticated Thor couldn’t be further from the prideful, hard-bitten, and haunted warrior of the comic runs that provided source material for these movies. Ragnarok is nominally based on the bold, almost revolutionary Walt Simonson storyline that ran from 1983 to 1985, an arc that begins with Thor (more spoiler alerts) shockingly losing his hammer in single battle to Beta Ray Bill, eventually seeing all-father Odin plunge to his (apparent) death in battle with the giant space demon Surtur, and finally undertaking a mad mission to confront Hela, the goddess of death, in the underworld, a journey he clearly does not intend to return from.

Thor, in fact, is saved from sacrificing his own life only by the substitute sacrifice of the equally embittered, hopeless Skurge the Executioner in a bravura sequence that culminates with the erstwhile villain achieving an unlikely, even poignant heroism.

The whole storyline pays tribute to Simonson’s favorite author, J. R. R. Tolkien, whose obsession with the inherent evil of the material world was forged precisely in his love for the elder Edda and the sagas of northern Europe. Simonson’s Ragnarok cycle hails from a centuries-long run of ice-bound tragedies, and his Thor is both more human and more hopelessly tragic than any Marvel writer had previously imagined.

From Tragedy to Parody

Waititi’s first Thor film largely reduces Simonson’s radical revisionism to clever parody. In the comics, Surtur spends eons forging his sword to finally bring about Ragnarok; when Thor confronts him on the doorstep of Asgard, Surtur tosses him aside after a brief, futile battle in which the God of Thunder has no chance.

In sharp contrast, Waititi’s Surtur is an easily vanquished figure of fun, a heedlessly bombastic CGI confection cleverly taunted and then merrily decapitated by Thor in the opening scene to the cheeky, propulsive underbeat of Led Zeppelin’s “Immigrant Song.”

Although Surtur does reappear near the end of the film in a kind of demon ex machina plot twist, his entire story of apocalyptic vengeance, plotted and prepared for untold millennia to finally vent his seething hatred, is treated as a comic cat-and-mouse routine in which the clever, self-baiting quarry happens to wield a magic hammer too powerful for the giant, flaming, but stupid predator to resist.

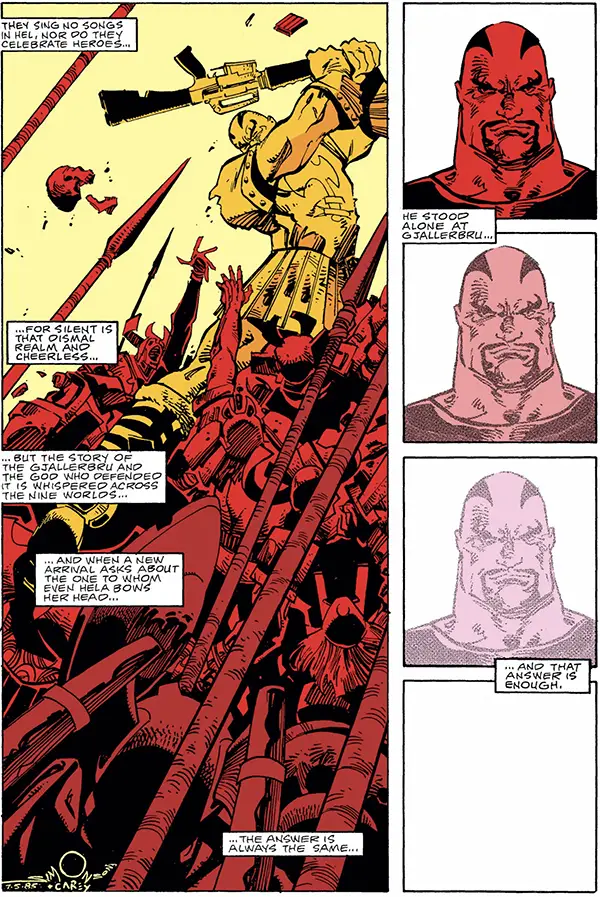

Skurge the Executioner is cut down even more sharply to caricatural dimensions by Waititi. In the comics, Skurge has lost all hope and the possibility of redemption, betrayed by the woman he has loved and bereft of his axe, which he has just used to destroy Hela’s battleship. Despairing, Skurge knocks out Thor with a sucker punch, dismisses Balder’s protest that he will surely perish in his attempt to secure their escape from Hela’s hordes, and is treated to one of Simonson’s most memorable series of panels to memorialize his sacrifice.

Simonson ennobles Skurge, who gives his life in a good cause because he now has nothing left to do but seek death. It’s a striking vision of valor from a god who will, because of his fateful choice to remain behind, never get to see Valhalla, the eternal home of those who die valiantly in battle.

Waititi’s Skurge, in sharp contrast, is a boasting buffoon right from the start of Ragnarok. He debuts early in the film trying to impress a pair of nameless, giggling Asgardian maidens with his knowledge of Bifrost, the mythical rainbow bridge that connects Asgard to Earth and the rest of the cosmos, and with the M-16s that he’s picked up from an exotic place called Texas. He’s soon covered in green slime and has to run all the way to the palace to collapse, as a punch line, at Thor’s and Loki’s feet, prompting the latter to trot out the staple stand-up comedian line, “You had one job to do . . .”

Later in the film, Skurge is cut off by a bored Hela the moment he starts to mumble out his pedestrian life story, and he later conceals himself in a woman’s shawl, trying to avoid joining the battle. When the demons of Hel come pouring in near the end, Skurge does finally doff the shawl and hop out with his machine guns to evoke Simonson’s signature image of the Executioner’s heroic end, but the comic qualities of his characterization up to that point overwhelm any possibility of nobility or sacrifice.

As played by Karl Urban, the Executioner of the screen is an appealingly comic character, a cringing softy who does finally answer the bell. But if Simonson’s colder, grimmer, congenitally darker Skurge ever came face-to-face with his meek screen counterpart, he would pole-axe him scornfully and walk away without a backward glance.

Blood and Gorr

The Thor of Love and Thunder falls even further from the tragic tree in the film’s disconcertingly whimsical treatment of perhaps the grimmest of Marvel’s Thor stories. Writer Jason Aaron’s Gorr the God Butcher storyline is a mix of horror, torture, and obsessive hatred that leaves past, present, and future Thors cut off from everyone and everything, fighting and losing across several timelines, over and over again, to the relentless God Butcher. Most crucially, Thor fights him alone, the battle increasingly spiteful, hopeless, and therefore all the more impossible for the incorrigibly stubborn Thor to abandon.

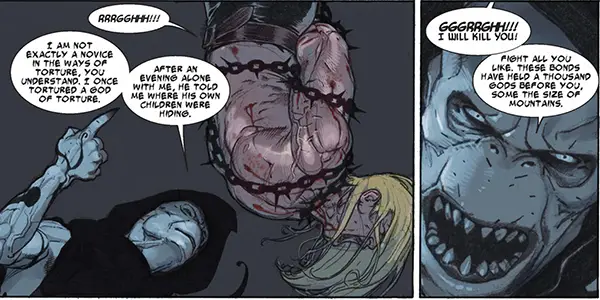

Gorr, it turns out, is Thor’s most deadly nemesis, a creature who has seemingly exorcised his own soul in his remorseless quest to take revenge on all gods. On the page, Gorr is a prodigy of hatred, bitterness, and implacable, overwhelming cruelty, not just another in Marvel’s endless run of world- and universe-conquering villains. Everything is personal for Gorr, and the pleasure he takes in torturing Thor to and past the limits of godly endurance is perhaps exceeded only by the pleasure he takes in knowing that none of the Thors can ever best him in combat, as stubbornly as they will always try.

Gorr, as his name suggests, is not merely an executioner, one who dispatches officially condemned enemies of a regime once and for all, but a butcher, an expert and insatiable sadist who relishes Thor’s pain as he tortures the blond battle-god panel after panel, issue after issue. Gorr’s stated goal is to erase all deities not only from present-day existence, but throughout all time, past, present, and future. But his real goal is to subject each and every one of them to the kind of unendurable pain that he feels the gods have subjected him to.

As a mainstream comic book character, Gorr is arguably unprecedented, an engine of unspeakable brutality and death. Just as horror films in the 2000s turned to torture porn after the revelations of Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo, Aaron’s vision of the God Butcher offers no hope or redemption, only monumental sadism, sacrifice, and loss. There are no Sunday morning pancakes anywhere in sight.

Daddy Duties

In bringing Gorr to the screen, Waititi and his scriptwriters made the fateful decision to use the kids of Asgard to emphasize his villainy. It’s a great marketing decision, of course, for any Disney product to follow Uncle Walt’s formula of relentlessly sentimentalizing the relationship between middle-class parents and their cutesy genetic copies, even if those scions of the middle-class hail from New Asgard. But the constant presence of children and all the middle-class clichés they bring make a travesty of Gorr’s icy, nihilistic rage.

We’re subjected to the helpless wailing of the anonymous parents and repeated declarations from the kids in Gorr’s space-cage that they’re scared, and not even Hemsworth’s impeccable comic delivery can rescue his pep talks or his temporary deputization of the children and their teddy bears to fight against Gorr’s remarkably inept shadow monsters.

Just as George Miller nearly killed off his Mad Max series with the sentimental treatment of abandoned children in Thunderdome, Waititi saps all the urgent energy out of Thor’s confrontation with Gorr by weighting him down with so much daddy duty. The god butcher story does not lend itself well (or, really, at all) to heart-warming family-values themes.

Comedic Love vs. Tragic Thunder

None of these criticisms are to say that Waititi’s Thor films are bad movies. They are snappy, light-footed, often delightful romps. But they steadfastly refuse to envisage, much less embrace, the Wagnerian grandiosities of their source stories, which they instead use as little more than narrative jumping-off points.

Tellingly, both films feature farcical stage performances of the tragic events from their immediate predecessors, making light of the deaths and losses that could, given different treatments, be legitimately moving.

In fact, these clever vignettes help Waititi demonstrate one of the most fundamental truths about the two counterpart genres: comedy is the greater, more flexible form, the one that can comprehend tragedy and all its losses and still affirm life in the end.

Waititi is, clearly, just such a comedian, the child of Maori and Jewish parents who knows the evils of colonialism and genocide quite personally, but who overcomes them in his work with life-giving and life-connecting humor, enmeshing the worst deeds of fallen human nature in scenarios that refuse to destroy everything, providing a vision always of new, hopeful life even after the horrors of history have done their worst. It’s a needful gift, certainly.

But a gift that’s an odd match for the grim world of Norse mythology, even the glossy, hyped-up Marvel version of it. That’s why Marvel should switch Waititi to the new character who makes a post-credits cameo in Love and Thunder, one who lends himself much more naturally to the director’s comedic sensibilities. Hercules, in sharp contrast to Thor, has long been treated by Marvel as a figure of fun, an incorrigible roustabout forever looking for a good fight and a good time. Hercules finds it almost impossible to take anything seriously, and that’s what would make him a superb vehicle for Waititi’s irreverent comedy.

More specifically, Bob Layton’s raucous 1982 mini-series Hercules, Prince of Power offers an almost perfect vehicle for Waititi. The bored prince so offends Zeus with his shenanigans at the beginning of the story that he is banished from Olympus, exiled to cruise the starways in search of the best liquor, brawls, and women in the company of a droid who’s supposed to record his exploits but ends up continually having to pick up the tab for all of Hercules’ (mostly benign) destruction. It’s an odd-couple comedy and road trip with plenty of action and ribald humor – just what the incorrigible comedian Waititi has pretty much reduced Thor to.

As for the Norse god of thunder, hopefully, Marvel will find a director who can use Hemsworth’s naturally warm, winning humor to deepen the horror of Thor’s tragedy, not just make it dissipate. The King Thor and Thor the Unworthy storylines from the comics could provide excellent vehicles as Hemsworth ages, but not if they too are transformed into comedies in which the heart-warming, reassuring love always drowns out the thunder. They should instead be entrusted to someone who will take their tragic qualities seriously. What’s Peter Jackson up to these days?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Brian Walter is a college professor by day and a hopelessly sleepy college professor by night. His work has appeared in a variety of literary and film studies publications, and he appears as an 'old coot' interviewer with a magic camera in the final chapter of Donald Harington's final novel, "Enduring." He lives a short walk from the St. Louis Zoo with his remarkably patient, loving wife and a quirky assortment of canine and feline familiars.