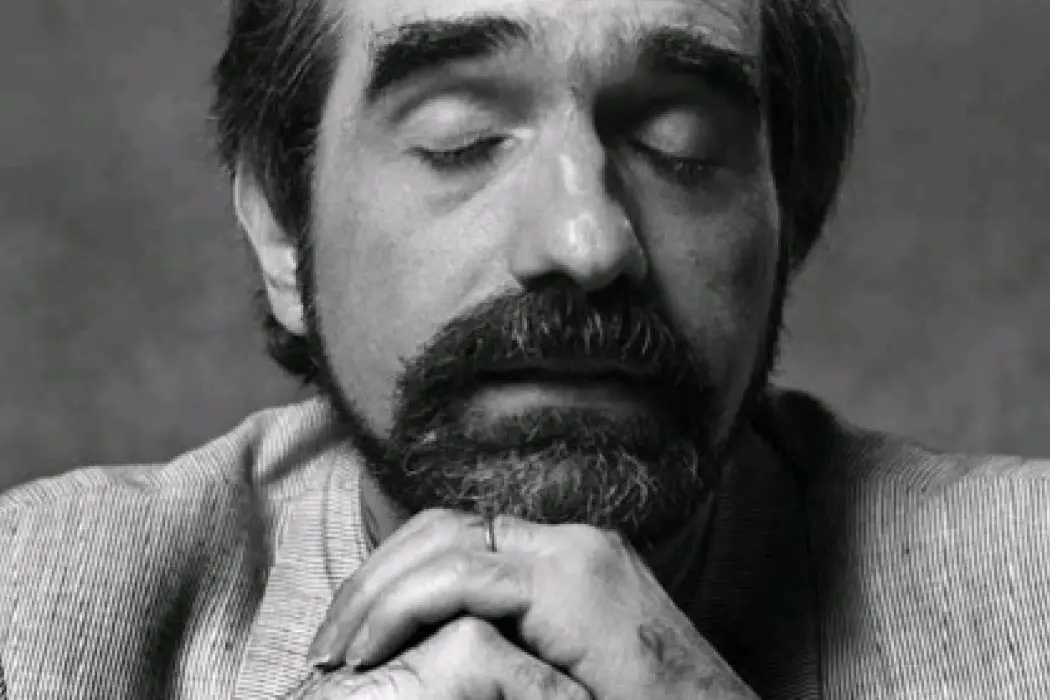

Martin Scorsese: In The Land Of The Blind, Content Is King

Darryl A. Armstrong works in marketing and advertising and writes…

Recently documentarian, film preservationist, and independent film producer Martin Scorsese faced a backlash over an essay celebrating the work of one of the 20th century’s most gifted artists, Federico Fellini. Scorsese writes of the enormous power of art and its redemptive properties, its ability to reshape society, its ability to inspire individuals thousands of miles or indeed years, decades, away. Of Fellini he specifies that his “films in which aesthetics and morality and spirituality were so closely intertwined that they couldn’t be separated, played a vital role in the redemption of Italy in the eyes of the world.” He calls Fellini’s work “precious” without irony and credits him with redefining Scorsese’s the “idea of what cinema was” for and “what it could do and where it could take you.”

The backlash, of course, ignored most of the essay’s affectionate, warm invitation for cinephiles and friends (that’s all of us) to revisit — or maybe discover for the first time — Fellini’s passionate, often dream-like oeuvre. Instead, it focused largely on an opening paragraph that derides the term “content” and laments streaming services that present everything “to the viewer on a level playing field, which sounds democratic but isn’t.” Scorsese’s critics latch on to the idea that he is somehow attempting to police their choices, a self-proclaimed gatekeeper of film. But I think it is important to remember that gatekeepers are also responsible for opening doors.

Part of the criticism was that Scorsese was perceived to have been attacking the institutions that have allowed him to shoot and distribute his own films. And in this respect, his current detractors fail to acknowledge his more universal complaint against film funding and distribution. Scorsese notes in the essay that Fellini himself — this great and influential and popular film director — had trouble financing and distributing his last film, The Voice of the Moon:

“He’d had a difficult time with his producers on that project — they wanted a grand Fellini extravaganza and he gave them something much more meditative and somber. No distributor would touch it, and I was truly shocked that no one, including any of the key independent theaters in New York, even wanted to show it. The old films, yes, but not the new one, which turned out to be his last.”

Meet The New Boss Same As The Old Boss

Much ink — and indeed a great deal of blood — has been spilled over the centuries over the ownership of art. Do the pharaohs of ancient Egypt own the massive tombs —architectural and artistic marvels — their long-dead bodies inhabit? What of the artisans and labourers and slaves who designed and built them — or, fast-forwarding to the present day, Egyptians and not various foreign, imperial powers? Does the Catholic Church own Michelangelo’s paintings in the Sistine Chapel? Does the French government own Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa? Does Disney own The Rocky Horror Show?

To answer that last question, yes — at least insofar as we as a culture agree to respect current Intellectual Property (IP) laws as they are regulated and enforced as sacrosanct. IP, of course, has become not just a term to refer to the legal idea of intellectual property, but as a way to refer to brands — Star Wars, James Bond, the Marvel universe. This muddying of the definition does no favors to the artists and creators of the stories and characters or to the fans who want to dress up as Batman or Luke Skywalker or Dr. Frank-N-Furter for Halloween. It does benefit the owners of the property, who can simply refuse to release or distribute the property based upon whatever criteria they deem relevant — and let’s not muddy any more definitions here, the criteria they deem relevant is profit. Profit, which does not benefit the creator or audience, but the — increasingly large, corporate — owner.

Film critic-acting-as-journalist Matt Zoller Seitz documented in late 2019 Disney’s “vaultification” of classic Fox films after their acquisition of 21st Century Fox:

“There might be a tendency to see all this as a niche issue, one that only affects nostalgists and people who are still enamored with the theatrical experience. But … theater owners… point out that the estimated 600 independent first-run theaters left in the United States are the only reliable incubators for independent filmmakers who are unlikely to have their work screened in multiplexes dominated by Disney and other major distributors. Many of them are international filmmakers, documentary filmmakers, and filmmakers of color who are going to lose access to these venues unless they’re subsidized by other events such as repertory screenings of old movies that can be relied on to draw crowds.”

The Last Algorithm

Scorsese’s observations aren’t just about the film industry, although they are specifically grounded in it. They are about our society, its cruel machinations to value profit and productivity and categorization above community and shared storytelling. They are also about us as individuals, who, overwhelmed with choices and content, look for guidance and easily obtained recommendations.

Indeed, another point of the backlash around Scorsese’s comments revolves around the idea of curation. And it may very well be that many of us do not view the algorithms employed by various streaming platforms as “curators,” whereas we do view a voice such as Scorsese as someone trying to curate for us. And it is true that the idea of curation in recent years has taken on a darker aspect as self-proclaimed curators flooded the internet shoveling reams of content at audiences that have less to do with careful, thoughtful recommendations than the whims of the moment. But the algorithms are far from neutral or even carefully selected.

The algorithms streaming platforms (who are increasingly also production houses) use are, to be blunt, not very good. They generally won’t recommend something outside of their catalog (why send you somewhere else to spend your money?), they routinely recommend things you have already seen, they are limited by terms and phrases and words you provide, and the more you use them the narrower your results become. But perhaps most significantly, they are just not human. They cannot share with you at length how La Dolce Vita shook them as a person over the “anxiety of the nuclear age” or how the characters from I Vitelloni felt like people “from [their] own life, [their] own neighborhood.”

All of this is not to say such algorithms don’t serve a purpose or will never improve. But criticism of an infantile technology is not a personal attack against its early adopters. It is unlikely now that the use of such algorithms will disappear, but it is also absurd to think its current form is anything close to optimal — or even comparable to a curated list of recommendations from another human being.

Scorsese asks, “If further viewing is ‘suggested’ by algorithms based on what you’ve already seen, and the suggestions are based only on subject matter or genre, then what does that do to the art of cinema?” It’s the type of question that certainly ruffles some people’s feathers. Is he implying my favorite type of movie, my favorite genre, is somehow devoid of “real value”? The answer is presented in the rest of the essay which explores the diverse career of Fellini, who directed the comedic, the dramatic, the historical epic, the fantastic, the introspective.

Tears In Rain

Scorsese’s homage to Federico Fellini is a tribute to an influence who crawled so that Scorsese could walk and a plea to let others run in their wake. Scorsese is the gatekeeper we need, but maybe don’t deserve, holding the gate open for filmmakers with stories to tell and audiences waiting to find new favorite movies — old and new — and lines to quote and characters to dress up as.

The blistering closing frame, bookending his remarks at the beginning of the essay that attracted so much attention, is as much a call for conservation as it is revolution:

“We can’t depend on the movie business, such as it is, to take care of cinema. In the movie business, which is now the mass visual entertainment business, the emphasis is always on the word “business,” and value is always determined by the amount of money to be made from any given property—in that sense, everything from Sunrise to La Strada to 2001 is now pretty much wrung dry and ready for the “Art Film” swim lane on a streaming platform. Those of us who know the cinema and its history have to share our love and our knowledge with as many people as possible. And we have to make it crystal clear to the current legal owners of these films that they amount to much, much more than mere property to be exploited and then locked away.”

Who owns art? Who owns film and the stories we share? We do.

Martin Scorsese, besides being a historian, activist, and essayist, is also the director of several films including Taxi Driver, Goodfellas, and The Departed.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Darryl A. Armstrong works in marketing and advertising and writes about pop culture. He is the co-creator of the Cyber Shorts Film Festival, and his work has been featured in Bright Wall/Dark Room, Rise Up Daily, and Image Journal's Arts & Faith Top 100 Films list. He lives in Las Vegas, Nevada with his two children.