If you’re a fan of a good gangster picture, then the chances are you’re a fan of Martin Scorsese. If you’re a fan of American cinema, nay cinema as a whole, then you are surely aware of the influence and mastery of the man they call Marty. From Goodfellas to Taxi Driver, Scorsese is the master of the riveting crime drama, and of burrowing deep into the lives and minds of extremely troubled people.

The reach of Scorsese’s influence spreads across the modern film industry from Joker to The Souvenir, and he is still furthering his art. With his new film The Irishman, the great director heads to Netflix and plays with fancy de-aging technology, in what is surely one of the year’s most highly-anticipated releases.

Despite Scorsese’s ubiquity in conversations about American cinema, New Hollywood, and tortured masculinity, there are still parts of his films that can go unnoticed. Throughout his filmmaking life, Martin Scorsese has been cameoing in his own films, sometimes obviously, sometimes barely noticeable in the background of a shot. It is no secret that several directors in the history of the movies have been fond of jumping in front of the camera, but few as much as Marty.

As fun as it might be to go back through his filmography and play a game of spot-the-Scorsese, it’s worth looking at these cameos with a more analytic lens. Why exactly would a director as famous as Scorsese want to pop up in front of the camera? Is he trying to ‘say something’, or is it all just a bit of fun? To get to the bottom of this, we can roughly split Scorsese’s cameos into three types:

Hidden in Plain Sight

Probably the most famous, and certainly the longest, Scorsese cameo was actually the least intentional. When we see Scorsese in the back of Travis Bickle’s cab in Taxi Driver, chillingly informing us of his plans for his cheating wife, we are scarcely aware that it was never meant to happen. The intended actor was unavailable on the day, so Scorsese stepped in. The ‘real’ cameo in the film happens earlier, when Scorsese sits on a wall admiring Cybil Shepherd’s Betsy as she strolls down the street. It is a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moment of a background-Marty, something that we find elsewhere too.

Scorsese is similarly removed from the action in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore as he munches away in the background of a diner. In Raging Bull and Who’s That Knocking at My Door, we do not even see the entirety of his face as he lurks in the corners of shots. Add to that the brief glimpse of Scorsese as a pool player in The Color of Money, a single line of dialogue in Boxcar Bertha, and several more brief appearances including Silence and Gangs of New York, and we can see how embedded Scorsese is in his films.

By appearing almost imperceptibly with each cameo, Scorsese weaves himself into the texture of his films, as if he is one of the screen world’s everyday inhabitants. The director has long been known for having a personal connection with his art, whether that be in the depiction of Italian-American life, Catholicism, or the Mafia.

It is hardly surprising, then, that Scorsese frames himself as belonging to the worlds he depicts; and it is no coincidence the cameo that has the greatest effect on a film’s narrative is his wordless role as hitman Jimmy Shorts in Mean Streets, long seen as Scorsese’s most personal, autobiographical film. Scorsese seems to exist within his films, and this is never more evident than in Mean Streets.

Man With a Movie Camera

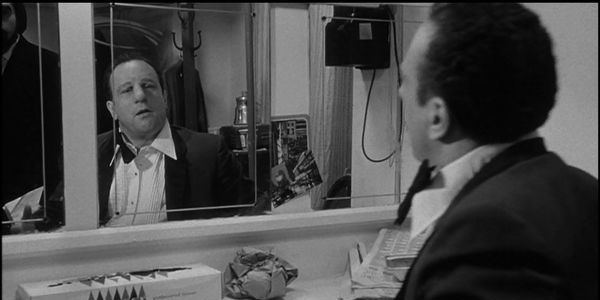

Despite almost none of Scorsese’s cameos lasting longer than a few seconds, there are some that stand out. Even if a brief appearance means his role fades into the film as a whole, there are some cameos where Scorsese does more than just sit in the background; time and time again we see him playing a version of his role as director. In The King of Comedy, he is a TV director; in The Age of Innocence and Hugo he plays photographers; in Raging Bull and After Hours he has no camera but is still a part of the theatrical process, as a stagehand and a spotlight operator respectively.

Crucially, in none of these films does Scorsese cameo as a film director, or rather, as himself; we only see him depicting various elements of the role of director. This allows the director to absorb himself into his fictional worlds, whilst subtly reinforcing the idea of him as ever-present creator. If his brief background cameos show that Scorsese is an integrated, passive observer of the stories he tells, then his appearances as a subtle version of his director self remind us that he is very much their author.

Hearing Voices

Martin Scorsese is an easy person to imitate, his nervous energy and New York accent make him an endearing caricature of cinephile enthusiasm. A dedicated Marty fan, therefore, should be able to spot not only when the director is visible in his films, but when he is audible. The voice coming over the radio as Nic Cage and John Goodman are on call in Bringing Out the Dead? That’s Marty. The man being scammed on the phone by Jordan Belfort in The Wolf of Wall Street? That’s Marty. The projectionist addressing Howard Hughes in The Aviator? That’s Marty.

In The Color of Money and Mean Streets Scorsese’s voice even plays the role of narrator, guiding us through the story. As well as playing a pivotal part onscreen in the deeply personal Mean Streets, Scorsese sets the whole film in motion with his opening words. This is the mark of a true storyteller and one who leaves his imprint on everything he creates. Plus, these vocal cameos allow Scorsese to make his films more enjoyable for his hardcore fans. The more hidden layers of authorial voice he adds, the more of an event ‘a Martin Scorsese picture’ becomes.

Conclusions

Whatever form a Martin Scorsese cameo takes, it deepens the understanding that you are watching one of his films. He is a rarity in being one of the world’s most distinctive directors, whilst seldom having a scriptwriting credit. Scorsese’s recognisable style comes not from quip-heavy dialogue or a Coenesque fusion of tones, but a kinetic visual approach, rock soundtracks, and unflinching depictions of violence, for sure. Despite this distinctive technique, Scorsese’s cameos display avid desire to continually leave a personal imprint on the films he directs.

Scorsese was a key figure in the New Hollywood movement that learned so much from the French New Wave and its auteur theory. If his cameos tell us anything, it is that Martin Scorsese is a true auteur, the real master of his movies.

Do you agree that Scorsese’s cameos reflect him as a filmmaker? Or are they just a bit of fun? Let us know in the comments!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.