Mainstream Avant-Garde Films In Latin America

All articles contributed by people outside of our team are…

What is considered Latin American art cinema today? Who defines the accepted hegemonic profiles of the films that receive funding and are shown all over at European film festivals? For the past 15 years or more, film institutions in the West, whose mission is discovering new artists with a different point of view, have developed a particular aesthetic favoring.

Strong intellectual opinions are not to be found in Latin-American films with observational narratives, minimalist mise-en-scène, natural lighting, no incidental music; with long shots of characters wandering a landscape where poverty and social and political issues might be implicit but not overtly developed. In general, this fashionable aesthetic usually favors the disappearance of manipulation by an auteur, contradicting the very nature of searching for a personal voice.

Third World Art Film

The result is that many of these films end up looking very much alike, dismantling the very concept of auteur cinema for which they were supposedly chosen. This new market of fashionable Latin American art cinema is becoming not unlike the bubble that plagued the visual arts, confirming the existence of two markets: commercial mainstream films and the emerging niche market of the “third world art film”. This market is designed for a somewhat-educated first world audience looking at Latin America as a sensorial landscape, rather than investing effort to learn its intricacies and contradictions.

It even goes as far as suggesting changes to filmmakers in order to fit the mold. Let’s take some examples in Cuba. Cuban filmmaker Armando Capó´s script for Agosto received support from several institutions, both in Europe and the US, but several changes were requested to fit their conception of what the film should be. Capó complained that it was very difficult to maintain his vision under these circumstances.

Films with a fragmented narrative, strong use of montage, stylized lighting, upper middle-class characters, or strong intellectual opinions are immediately discarded, as if that aesthetic can only be the province of developed nations in the West.

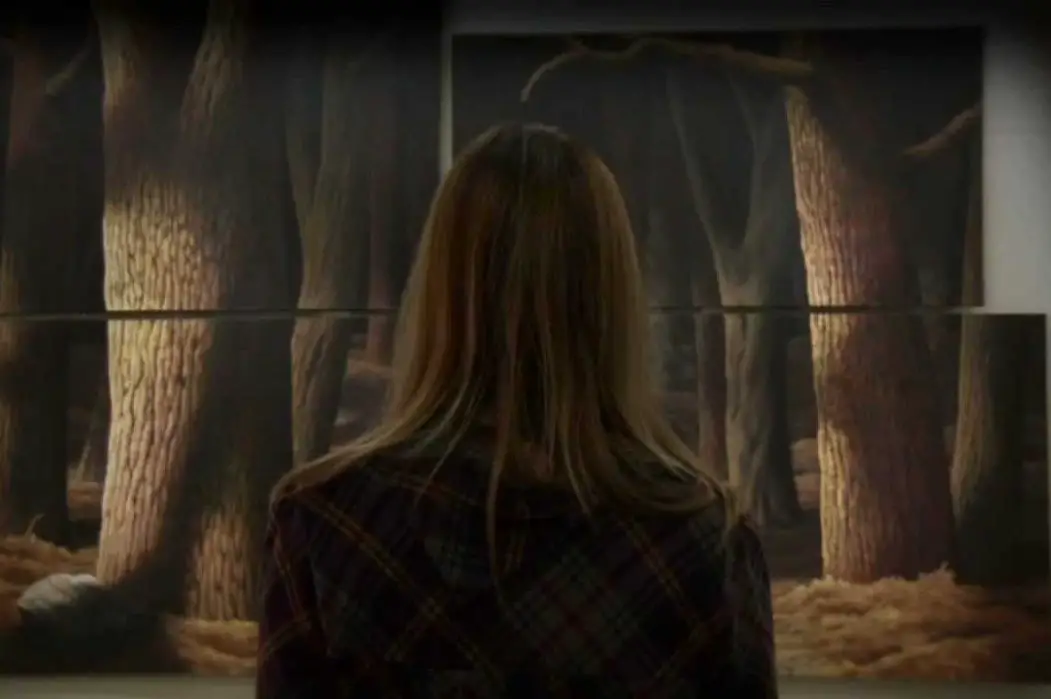

And what are these first world audiences conditioned to expect from third world cinema? A distant window, peeking at another culture from the safety of high above. This is not too different from decorative art: nothing too uncomfortable for either the eyes or the mind to digest. The poverty of the working class is almost always seen through this condescending gaze; the characters suffer and yet rarely are aware of the forces that create their agony, and even less are they ready to confront those forces.

Outside of Pornomiseria

Cuban filmmaker Jorge Molina, whose work has been characterized by an extreme mixture of explicit sex, gore, science fiction and horror, can’t find any institutions willing to fund his films. Resultedly, he’s ended up in no man’s land since his work is deemed too extreme for both mainstream and arthouse tastes.

The term “Pornomiseria” (misery-porn) has been criticized by many Latin American filmmakers and scholars. The term is a critique to filmmakers who abuse the underdevelopment and marginal settings in Latin-American films as an excuse to draw the attention of a foreign audience. Many filmmakers are even crafting their projects from the initial stages to fit this mold and get funding, while a few filmmakers use it as only as a selling point to later revert to their original concept once they obtain funding.

Carlos M. Quintela´s La Obra del Siglo is an example of a film that managed to escape the nature of its original conception. The minimalist story of three men, three generations, living in a small apartment building, gained an enhanced political context when the filmmaker discovered documentary footage of the Cienfuegos Nuclear Power Plant and subsequently relocated his story to this new setting, creating a hybrid of fiction and documentary. However, it is doubtful that the Huber Bals Fund, the institution that funded the original script, would have approved the increased complexity of the finished film.

This is another precedent on how important it is to divorce from written ideas. In today’s film world, I find that the most interesting projects are improved with the chemistry of improvised elements finding their way into the narratives. Of course, this makes it rather difficult when institutions require a detailed description on paper of what will be on screen.

Filmmakers And Film Festivals

It’s difficult today to find anything completely original. It’s the combination of influences which combined can create a true unique voice, but in an increasingly globalized world even some of these alternative films are rapidly labeled, and sales agencies jump in to make a business out of it, even if it’s just for a niche audience. The filmmakers then remain happy with the formula they concocted and very seldom venture into truly new territory.

In this world, the filmmaker has a much higher rate of success by befriending festival programmers and learning their tastes, sometimes valuing them more than artistic quality. Even festival awards are given because of pre-arranged benefits with sales agencies that act as distributors because they know the films are not commercial enough to release. These films remain available only to the academic world, since domestic distribution won’t make dividends for a sales agency. Needless to say, these films hardly even play in their native countries.

On top of that, submissions fee at international film festivals are almost a must. Only a very small number of films that have been programmed by many festivals have been submitted via the official submission channel. The rest are either recommended or the festival takes interest in contacting the filmmaker directly. The submission fees of rejected films end up as a source of income to the festivals. In other words, rejected independent filmmakers end up funding festivals where they don’t participate.

Carlos M. Quintela´s latest film The Wolves from the East is a mature story about isolation and nostalgia. The film takes place fully in Japan with a Japanese protagonist. If Yasujirō Ozu had made this film, the press would revere it, but a Cuban filmmaker made it and that’s not what international audiences expect from him. So the film has fallen into a cultural and geographical limbo, which has made the film difficult to program at festivals.

Conclusion

Now, for my agitprop rant: I find the vast majority of supposed “art films” highly irritating, because the compromises become more and more detrimental to our truly exploring the medium. A few programmers and curators seem to be fixated on an aesthetic regardless of what an intelligent audience (devoid of snobbish classism) would be capable of enjoying. These people are as responsible as the Hollywood suits for delaying the evolution of cinema language.

An independent filmmaker must be independent not just in the way he or she obtains financing, but mostly in form and content.

About Miguel Coyula

Miguel Coyula is a Havana-based Cuban filmmaker, published author, and Guggenheim Fellow whose lauded work has been screened and awarded around the world. Most recently he produced a webseries and documentary feature (Nadie) on the late poet Rafael Alcides, the latter of which screened at MoMA and won Best Documentary at the Global Film Festival in Santo Domingo. Currently Coyula is working on his fourth feature, Corazon Azul (Blue Heart).

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

All articles contributed by people outside of our team are published through our editorial staff account.