“Live from New York, it’s Saturday Night!”

This opening salvo has been the rallying cry of NBC’s Saturday Night Live for a whopping 43 seasons. The revolving cast of ‘Not Ready For Primetime Players’ reads like a Who’s Who list of comedy royalty. From modern standouts like Amy Poehler and Maya Rudolph to gold standards like John Belushi and Eddie Murphy, each generation of viewer has their own comedic muse.

It may come as a surprise, though, that the first cast member recruited for its 1975 debut was actually Gilda Radner. After watching Love, Gilda, a new documentary about the vivacious performer’s rise to stardom and her brave fight against ovarian cancer, it’s clear that Radner was a wise choice to lead the inaugural cast into battle.

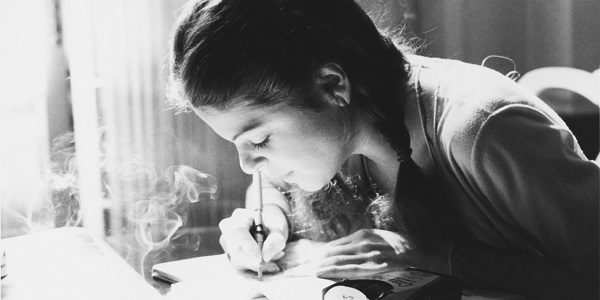

Director Lisa Dapolito peppers her film with plenty of classic footage from Radner’s tenure on SNL, as well as interviews with friends, family, and colleagues. What really makes Love, Gilda special, however, are the home movies, audio recordings, and journal entries compiled by Radner herself over the years. Inspiring, thoughtful, and painfully intimate, it’s impossible not to be moved by this melancholy story of a young woman desperate to overcome her insecurities through the power of laughter.

The Dancing Fat Girl

Watching the 1950s home movies of a young Gilda Radner – mugging for the camera and pirouetting as fast as her chubby legs can take her – it’s hard to imagine she has a care in the world. This self-described “Detroit Jewess” grew up a child of privilege; the cherished daughter of a successful hotelier who migrated his family to Miami Beach every winter just to avoid the Detroit cold. Working from the extensive archive of Radner’s own audio cassette recordings, first time director Lisa Dapolito uncovers something even colder lurking behind the little girl’s ever-present smile.

“Because I’m not a perfect example of my gender,” Radner laments over scratchy recordings, “I decided to be funny about what I didn’t have instead of worrying about it.” It’s one of several heartbreaking admissions from Radner, who never shies away from looking inward and sharing her deepest, most intimate stuff. Morbidly insecure about her weight as a child, Radner adopted a self-defense mechanism that would not only protect her fragile psyche, but eventually propel her into the national spotlight. She became a performer; a player of roles designed to deflect criticism and make people laugh.

“Hitting on the truth before the other guy thinks of it,” she reasons.

It’s in these earliest recollections that Dapolito begins to sketch the thematic trajectory of Love, Gilda. A little girl, desperate for love and attention, becomes so adept at role playing that the persona overshadows the person. Each buried insecurity spawns a new character, more outlandish and hilarious than the last, further obscuring the real Radner from view.

Unfortunately, Dapolito’s timid narrative choices sometimes undercut the thematic heft of the film. The death of Radner’s father, for instance, is fleetingly discussed, despite the adoring Radner being only 14 years-old at the time. It’s interesting to learn that the family caregiver, Biddy, served as the inspiration for one of Radner’s most iconic characters (the eternally confused Emily Litella), but skimping on the impact of her father’s death seems like an oversight.

Barely mentioned, too, is the shameful story of Radner’s image-obsessed mother putting her overweight daughter on the diet drug Dexedrine when she was only 10 years-old. Given Radner’s struggles with bulimia and anorexia as an adult, this is a thread of inquiry too psychologically relevant to ignore. Perhaps Dapolito wishes to avoid negativity out of respect for her subject, but it’s this very negativity that shaped Radner’s life, both personally and professionally.

Gilda Was A Girl Before Being A Girl Was Cool

In this time of all-female comedy re-makes such as Ocean’s Eight and Ghostbusters, it’s easy to forget that audiences weren’t interested in female comediennes back when Saturday Night Live premiered. Lucille Ball, Gracie Allen, and Elaine May might have been a distant memory when Radner started performing in the early ‘70s, but that didn’t stop her from embracing her femininity in every role she played.

“I am a girl,” Radner explains in her journal. “I never wanted to be anything else.”

Dapolito rightfully trumpets Radner’s role as a trailblazer for future female comics and actresses. Amy Poehler, Maya Rudolph, and Melissa McCarthy each acknowledge that her contributions were pivotal in making comedy more accessible to women. Poehler even admits to stealing many of the characters in Radner’s repertoire.

Love, Gilda really soars when it focuses on this chaotic period in Radner’s life. Archival photos and audio recordings highlight her time with the infamous “National Lampoon Radio Hour” and the influential Second City comedy troupe. Eventual legends such as Martin Short, Bill Murray, and Harold Ramis cavort alongside Radner, who looks to have finally found her niche. Were it not for her own intimate recollections, we might not guess what an insecure mess she really was.

Several key players from that era also lend their thoughts. Martin Short, who briefly dated Radner, remembers an energetic girl who couldn’t sing to save her life. Saturday Night Live alums Chevy Chase and Laraine Newman also sing the praises of their fearless co-star.

Sadly, most of the SNL crew does not appear. Hearing from Jane Curtin, a female trailblazer in her own right, might have yielded more insight about Radner’s struggles inside the boy’s club of comedy. Murray and Dan Aykroyd are also noticeably absent. Perhaps Aykroyd was too busy not producing a new Ghostbusters movie.

Live From New York…

With a backdrop of disco music and garish clothing to punctuate the turbulent ‘70s, Dapolito tracks Radner’s ascension from underground phenomenon to television star on Saturday Night Live. What makes her accomplishment especially impressive is that Radner wasn’t particularly spectacular in any specific area of stage craft. She could barely carry a tune, wasn’t a very good actress, and readily admits she couldn’t dance. One of the unquestionable highlights from Love, Gilda is Radner’s ill-advised dancing duet with Steve Martin; a segment made riotously funny precisely because neither one of them can dance.

What she could do, however, and what made America fall in love with her, was play entertaining roles with complete conviction. Dapolito splendidly recalls Radner’s childhood insecurities by featuring clips of her most famous characters. The adorably nerdy Lisa Loobner subjugates herself to the will of her boyfriend, the hyper-imaginative Judy Miller hosts a one-woman show in her bedroom, and the obnoxious hairdo that is Roseanne Rosannadanna embraces her inner slob.

The more famous Radner became, however, the more her insecurities dragged her down. “I’m a rising star with heavy chains attaching me to a hard ground,” she writes in her journal. What Love, Gilda makes achingly obvious is that those chains were a product of her own devices. This woman, so adept at playing lover to her co-stars and the Girl Next Door for America, never felt worthy enough to just be herself.

Oh, How The Mighty Have Fallen

With her run on Saturday Night Live ending in 1980, Radner followed her television success with a failed marriage and a string of dreadful films (when Hanky Panky is a highlight, it speaks volumes about the quality of your filmography). Her self-esteem was shattered and she was eventually hospitalized for anorexia and bulimia after her weight dipped to a startling 96 pounds.

Even when she meets her soulmate, the equally legendary performer Gene Wilder, she’s compelled to play a role in order to secure his affections. She takes tennis lessons to satisfy his love of sports and learns French because he loves vacationing in France. Radner eventually leaves behind her life in New York City and disappears into Wilder’s Los Angeles mansion.

Strangely, Dapolito fails to explore this down period in Radner’s life and it greatly undermines the themes she has so carefully crafted. Yes, Radner finds a modicum of happiness, but at what personal cost? As she has done throughout her life, she molds a new identity in order to satisfy a lover. Dapolito misses a valuable opportunity to tighten the psychological threads within Love, Gilda by ignoring this fact.

Love, Gilda: Conclusion

The final act of Radner’s life begins in 1986, when she’s diagnosed with ovarian cancer. For nearly three years she battles the disease, still trying to make her friends and loved ones laugh despite needing their constant support. “I thought I was supposed to be the jester,” Radner laments, “now I feel like the beggar.”

With her treatment options nearly exhausted, Radner embarks upon her final role; to be an example for cancer patients. She pens her autobiography It’s Always Something and even makes a guest appearance on It’s Garry Shandling’s Show. Ironically, in facing her own death, Radner learns that she was always strong enough to survive on her own.

Dapolito tastefully renders the final days of her heroine’s life through home movies shot by Wilder. Radner bathes in the warmth of friends and family, putting on a happy face until the very end. This finale also benefits from a delicate score by Miriam Cutler, who shows a deft understanding of when to be whimsical and when to be wistful throughout the film.

Ultimately, Love, Gilda works as a splendid tribute to one of America’s comedy legends. While it does struggle to deconstruct Gilda Radner’s psyche, it has no trouble reminding us of her brilliance. Mostly, it’s just nice to hear Radner’s voice again. This is a must-watch for fans of Saturday Night Live, regardless of your age.

What is your favorite Gilda Radner role? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Love Gilda was released in the US on September 21.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.