LONG STRANGE TRIP: The Grateful Dead In The Exploding Moment

Eric D. Bernasek lives on the island just north of…

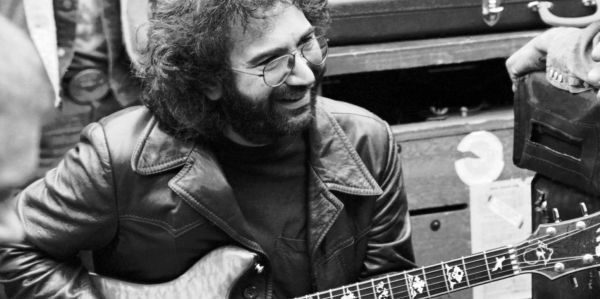

Somewhere on the way to the end of the first hour of Amir Bar-Lev’s four-hour Grateful Dead documentary, Long Strange Trip, the director sets up a mission statement of sorts for Dead Inc. In a word: fun. It’s the apotheosis of a section about the band’s participation in Ken Kesey’s legendary “Acid Tests,” where they were the house band to the counterculture’s bold quest for states of being then uncharted in Western culture. We hear Jerry Garcia, a one-man symbol of not just the Grateful Dead but a whole era of American popular culture, describe a pivotal moment in the formation of the Dead’s ethos.

Just before dawn, after another night of dropping acid with Kesey’s Merry Pranksters and surrendering to the psychedelic flow – a night Jerry calls “particularly strange” – they drove the Pranksters’ iconic bus to the Watts Towers in Los Angeles. As a testament to idiosyncratic artistic expression, Sabato Rodia had spent over three decades building the towers from steel rebar, concrete, wire mesh, and discarded tile and glass. When Rodia died, the City of Los Angeles tried to tear his towers down, having long fought him over permits never granted, but ultimately relented, finding it easier to sanctify the artist’s life work as a tourist attraction.

Bathed in the hazy afterglow of an all-night excursion, both psychedelic and creative, and resting on the precipice of an era that would come to transform American culture, Jerry looked at Rodia’s creation and thought, “If you work by yourself as hard as you can every day, after you’re dead you’ve left behind something that they can’t tear down.” Garcia’s real takeaway, however, was less obvious: “That’s not it, for me. Instead of making something that’ll last forever… I think I’d rather have fun.”

The Exploding Moment

It’s an extraordinary moment in a documentary full of them. But establishing an overarching theme is not an outrageous or even a particularly noteworthy thing for a documentary to do. It’s what comes next that hints at why Bar-Lev’s paean to the Grateful Dead is truly superlative.

At the start of the second act – one of six, each 40 minutes or longer – Mickey Hart, one of the Dead’s two drummers, waxes philosophical about percussion: “Drums give their life in the playing. They decompose… We beat ’em up.” It seems like Hart is carrying on with the theme of impermanence that ended Act I, but things go sideways when he goes on to say that he’s been building a “time and space machine,” making digital samples of all the drums in his collection.

It’s typical cosmic Mickey. It’s also a segue to the next shot, in which we see the first of several present day images of the band’s colossal archive, visually reminiscent of the final scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark – a nameless employee wheels a cart of rare and potentially dangerous treasure down a seemingly endless hallway stacked high with other treasures equally unknown. The Dead’s other guitarist, Bob Weir, draws out the irony: “It’s almost inescapable that if you work at something, you’re gonna build something.”

This is just one of the many curious paradoxes that were characteristic of the Grateful Dead. The scene reveals the contradiction between what the band set out to do – and to avoid doing – and what they achieved, almost by accident. Despite Garcia’s vow to have fun and not give a shit about posterity, the Grateful Dead has become the most exhaustively documented band in the history of rock. In 2015 there was a fair amount of journalistic bemusement at the release of the band’s 80-disc box set “30 Trips Around the Sun“, but that was just one in an imposing list of multi-disc box sets, some of which have documented entire tours in the Dead’s 30 years of live performance. Practically every note they ever played for an audience has been captured on tape.

The film’s visit to the vault – during which Weir unearths the first of a few previous attempts at a Grateful Dead documentary – demonstrates a great irony in the story of the band. But, so early on in the film, it’s not belabored or even stressed. In fact, it’s barely acknowledged at all. Bar-Lev’s narrative circles back to it later on, but for now it just plants a seed. In response to Jerry’s call to adventure at the end of Act I, it’s as if the film is saying, “Yeah. About that…”

“We’re the same as you. You’re the same as us.”

It’s just that sort of nonchalant yet pointed juxtaposition that makes Long Strange Trip an outstanding rock and roll narrative. It is completely unafraid to gaze at not just the bright but also the dark parts of the Grateful Dead’s history. Pop music documentaries tend to steer towards the most sensational aspects of their subject’s lives, due in part to the VH1 series Behind the Music and a long string of melodramatic biopics, from Great Balls of Fire! to Walk the Line. But the darkness here is neither indulgent nor cynical. It’s respectful and, more notably, honest.

John Perry Barlow, one of the band’s two lyricists, helps to shine a soft light on the darkness at the heart of the Grateful Dead: “These guys are a real swaggery… macho lot. The idea of somebody from inside that scene crying… You just… You didn’t do that. Well, f*ck. Sometimes it’s a good idea to cry. And we’ve got a lot to cry about, frankly.” It just so happens that the Grateful Dead – a band that symbolizes sixties sunshine and hippy rainbows to so many – actually suffered through quite a bit of existential agony alongside their psychedelic ecstasy. And they expressed that dichotomy in their music, once again despite the image of them typically portrayed in the wider culture.

Quite a bit of the film’s narrative is devoted to how this dichotomy affected the life of Jerry Garcia in particular. Nick Paumgarten, Dead fan and regular contributor to The New Yorker, touches on this in his description of Jerry’s final days: “It suited the music he was performing, when he was shrouded in death. Because a lot of Garcia’s music is about death. That’s an appeal to the man that you have to discover over time. You don’t see it immediately, because of the way he presents historically as this sort of big, happy hippy icon. You get to know, if you listen to the music, that actually he’s a deliverer of dark news.”

All of that may sound pessimistic, but keep in mind that these are but drops in a very big bucket. Bar-Lev has his work cut out for him, not just in telling a condensed and coherent version of a truly epic tale but in balancing the popular misconception – and, frankly, the cultish in-group nothing-but-positive-vibes mentality – with some basic, albeit negative, facts about Garcia and the Dead.

To put it another way, Long Strange Trip is out to tell a story, but it does not mythologize. It celebrates its subjects by letting them be human, because the things that made them ordinary are as important to the story as the things that made them unusual. It’s largely due to this tendency to humanize rather than mythologize that the familiar rock and roll narratives –about the perils of mainstream acceptance, about selling out, about excess, about addiction – are kept from being sensational. Instead, they feel relatable.

Thinking Man’s Dead

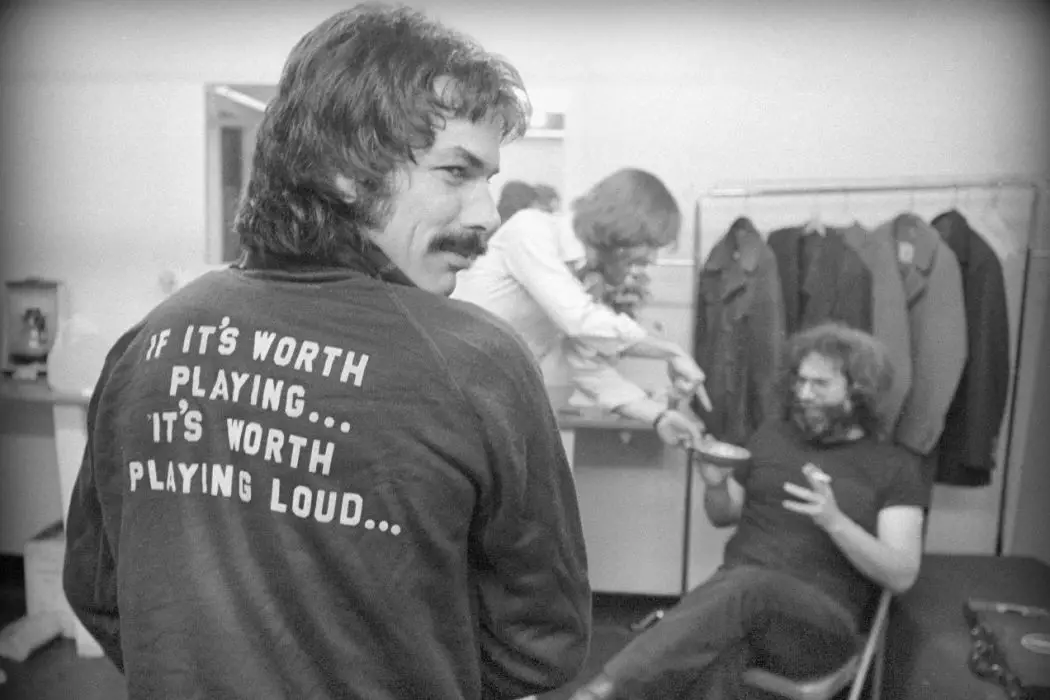

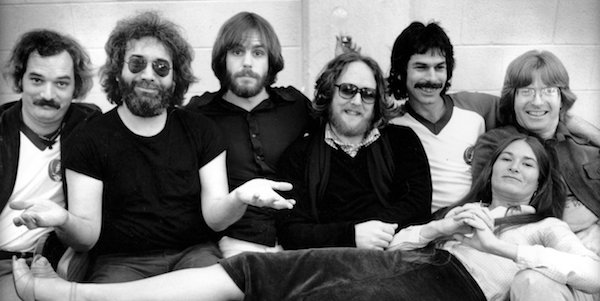

Another healthy share of that relatability can be attributed to the characters that Bar-Lev puts on screen. There are, of course, the band members themselves. The years they spent playing together have won them realizations musical, mystical, and practical that they dispense without pretension. Garcia, who died in 1995, is included through the many interviews recorded while he was still alive.

And then there’s Bob Weir, sitting cross-legged on his meditation cushion, his at last no longer boyish face obscured by the sort of white whiskers that belong on a prospector in the time of the California Gold Rush. His voice has an awe-shucks country twang, but his diction meanders endearingly from folksy to erudite. In one choice sequence he echoes Garcia’s commitment to fun: “In eternity, nothing will be remembered of you. So why not just have fun? I guess it’s probably a diminutive way of saying something that people have tried to enshrine in much loftier terms. You’re there in the exploding moment. And I was there with him. And I was down with that. Yeah. Let’s have some fun.”

There’s also Robert Hunter, the Dead’s reclusive and enigmatic lyricist, sprawled out on a chaise – as if he’s with his analyst – being coy about the lyrics to his most famous and most abstruse song: “Well, let’s see… Dark star crashes, pouring its light into ashes. Reason tatters. The forces tear loose from the axis. Searchlight casting for the faults in the clouds of delusion. Shall we go, you and I, while we can, through the transitive nightfall of diamonds… What is unclear about that? I mean, it says what it means.”

In this documentary, even the roadie is a philosopher. Steve Parish, still wide-eyed and rough-and-ready, offers pearls of real wisdom about who and/or what might be the boss. And the tour manager, Sam Cutler – who brags nonchalantly that “all the drugs I would ever need are wherever I happen to find myself” – demonstrates on camera that he lives amidst his own unfolding narrative; hardly an instant after he declares that the job of a tour manager is to be “prepared to deal with anything,” the cops show up to pull him over.

Intellect may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of the Grateful Dead, but Bar-Lev’s documentary is very much an intellectual one. Aside from all the sages aforementioned, there are also the amiably astute but still far out pontifications of Deadhead journalists Nick Paumgarten and Steve Silberman, who uses the Buddhist mandala as a metaphor for the various communities at Dead concerts in a way that is uniquely illuminating.

To latter-day outsiders the Grateful Dead was a band meant for, if not aging hippies, frat bros, trustafarians, and wooks. In the last few years before Jerry Garcia died, Dead tours had become a traveling circus, where the party outside an arena was often more heavily attended than the concert itself, and the longevity of the scene was threatened by gatecrashers and assorted lawlessness. It’s to Bar-Lev’s credit that Long Strange Trip deflates this image of the Grateful Dead Universe and instead offers an articulate, deeply thoughtful, and refreshingly intelligent look at what the band was really all about.

Which is not to say that drugs didn’t play a part. They did. And the film spends a not insignificant amount of time trying to explain what an acid trip is really like and precisely why that might help to understand the Grateful Dead. At one point Jerry calls the psychedelic trip “the most significant experience of my life,” a sentiment that’s echoed by the rest of the band, each in their own ways. But anything any one person can say about that experience is also demonstrated by the film, not with the tired “trippy” clichés we’ve seen a thousand times but in a constant return to deeper meaning and interconnectedness that draws lines between otherwise unrelated moments.

One Man Gathers What Another Man Spills

Despite what you probably expect, the worst thing about Long Strange Trip is that it’s too short. Even with a running time that pushes four hours, there are still so many things it leaves out. So little time is spent on the band’s studio albums, for instance, that the film gives the impression that their third album was their first and, for that matter, it only really mentions four or so out of nearly a hundred and fifty official releases.

The legendary concert promoter Bill Graham is never mentioned by name, despite his being instrumental in the Dead’s success. Actually, with a lineup of musicians that expanded and contracted and otherwise changed in a number of significant ways over thirty years, there are even band members who aren’t mentioned in the film. A significant part of one section is devoted to Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, a founding member of the Dead who died in 1972, early in the band’s rise. That section is followed by a single shot including portraits of the deceased members of the Grateful Dead’s extended family as an efficient way of admitting just how many more people have been left out.

This is just one of several ways in which Bar-Lev manages to cram an overwhelming amount of content into a space that should be too small. It’s a mammoth film, certainly. But the four hours you spend watching Frederick Wiseman’s At Berkeley will probably feel longer than the four hours of Long Strange Trip, whether or not you like the Grateful Dead.

One of the ways the film gets away with this is by avoiding a strict chronology – while being more or less chronological – and dealing with themes instead of events. It also employs a few useful devices, much like recurring musical motifs, that lead the viewer back from whatever distant point on the internal landscape the narrative may have wandered. For one, there’s the repeated use of an actual musical motif – the tune to St. Stephen, one of the Dead’s oldest and most distinctive songs – and then there’s Frankenstein.

Frankenstein’s monster was special to Garcia. One of his last interviews was for a series on AMC called The Movie That Changed My Life, during which he talked about seeing Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein when he was six years old. Throughout Long Strange Trip Bar-Lev uses excerpts from James Whale’s 1935 movie The Bride of Frankenstein to re-engage the viewer, anchor the story, and offer some contextual resonance through free association.

But, more than anything else, the efficiency of Long Strange Trip can be attributed to editing, with which Bar-Lev was assisted by Keith Fraase and John W. Walter. A number of particularly effective sequences enlist two or more people in telling parts of the same story. It’s a creative and conversational approach that helps to tell a more economical story and, not for nothing, can at times feel more than vaguely psychedelic.

Bar-Lev’s Choice

Long Strange Trip is the eighth documentary for director Amir Bar-Lev, whose previous works include My Kid Could Paint That, The Tillman Story, and Happy Valley, about Jerry Sandusky and the child sex abuse scandal at Penn State. His work on Long Strange Trip began with his contacting the Grateful Dead in 2003, almost fifteen years ago, and has been a true labor of love since that time. His devotion for the Dead is a clear element of the film, but it’s his skill as a filmmaker that makes Long Strange Trip a movie that even non-believers can appreciate.

How do you think Long Strange Trip compares to other rock and roll documentaries?

Long Strange Trip is now available to stream on Amazon Prime Video.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Eric D. Bernasek lives on the island just north of the island that is Montreal. He thinks too much and writes too little. He is currently working on a book about movies from your childhood: "Does Barry Manilow know that you raid his wardrobe?" – Authority and Rebellion in Movies About High School.