‘History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes’, Mark Twain apocryphally said. This aphorism circled around my mind watching Rubika Shah’s documentary chronicling Britain’s 1970s Rock Against Racism movement, an anti-racist and anti-fascist group which sprung up in response to the racism and pronounced fascism of some of Britain’s most beloved rockers. Twain’s alleged quote hovered throughout White Riot’s 80 minute runtime via archive clips of hateful leaders and bigoted individuals that we like to think of as firmly in the past. But while the language of today’s world leaders and internet trolls do not repeat the language of the proud racists of 40+ years past, it certainly does rhyme.

Reminders and Revelations of Racism Past (and Present)

An expansion of her 2017 short film White Riot: London, Shah kicks the film off as any respectable 1970s London-set punk documentary should: with The Clash’s London Calling marching over the opening titles. Right from the off Shah makes clear that she’s going to show you the bigotry for how it is– or how it was. Rock Against Racism (RAR) was formed in 1976 primarily as a reaction to the racist remarks of ‘rock’s biggest colonialist’, the legendary blues guitarist Eric Clapton (a colonialist due to making his fame playing the blues: a genre originated by black workers, notably in the slave trade). The comments of Clapton – still unbeknownst to many –drew audible gasps from the audience. Shah places the remarks in quotes on screen minutes into the film: they are blunt, hit hard and illustrate just what our heroic rockers were fighting against.

One rock hero down, Shah then turns another, focusing on the remarks of Ziggy Stardust himself, David Bowie, who at the time believed that, ‘Britain could benefit from a fascist leader’. And Rod Stewart, like Clapton, stated that he believed Britain should be for whites only. Co-founder of RAR, Roger Huddle, tells us that he hasn’t listened to Stewart since.

Huddle’s comment brought to my mind the question most recently posed by the Michael Jackson documentary Finding Neverland: should one stop listening to an artist if they’ve done something awful? But White Riot has no interest in discussing this, and I felt slightly and rightly chastised for pondering such an academic question in light of the subsequent footage of the racism that RAR were trying to rock against: the fascist National Front political party sieg heiling in the streets, marching through black and Asian communities, openly and proudly using the language of Nazism. ‘We know where that led’, RAR co-founder Red Saunders says, ‘that leads to the trains’, recalling the trains that transported Nazi victims to concentration camps. And it wasn’t just National Front extremists RAR were fighting; it was British society, too. ‘Our job was to peel away the Union Jack and show the swastika’, says Saunders, bearded, bespectacled and wearing bright red braces.

With the footage to prove it, Shah shows us how racism was the norm, strewn throughout popular TV shows, commercials and, indeed, music.

The Documentary Equivalent of a Punk Song

But the film isn’t all bleak because the history wasn’t all bleak. The tone of Shah‘s film reflects her story: grim in parts, sure, but one that is ultimately made optimistic by anti-racist rockers, reggae artists and punks. Shah tells the story through the soundtrack of the musicians, the Sex Pistols letter-cut-out punk aesthetic, new interviews with RAR founders, members, activities and surprisingly high definition footage and pictures. Indeed, the documentary harnesses the optimistic and grit of its story, carrying the aesthetic and energy of a punk song: brief, feisty, angry – but with something to say.

There are short sections where Shah perhaps fails to provide enough context, particularly for unacquainted non-UK audiences, for instance in quickly moving to discuss the intersectionality between the English RAR and Northern Ireland during The Troubles. And what we now call intersectionality is addressed in brief interviews with activists highlighting the connection between the discrimination of ethnic minorities and LGBT+ people. Brief, however, is the key word for this exploration.

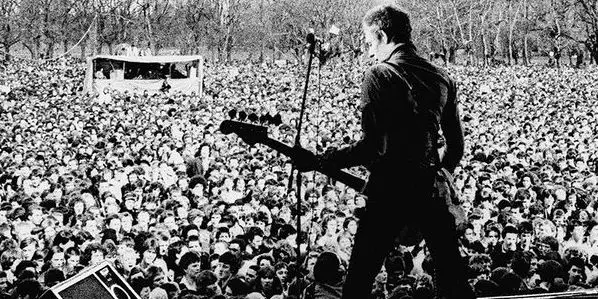

It’s a streamlined story, tight and energetic like the punk tunes that throb throughout, focusing on the achievements of the anti-racists as much as the grim reality of their opponents, culminating in the 1978 Victoria Park concert, full of footage for fans of Tom Robinson Band, The Clash and Steel Pulse.

A Righteous Riot

From a distance of over four decades, the racism of the 1970s is unambiguous. Shah gives us video of the National Front calling for Britain to remain white on one hand, and on the other, when trying to put an acceptable face of its racism, their sloganeering, ‘Get the muggers off our streets’. One can see, from the perspective of 2019, the euphemism of the term ‘muggers’. One can also sit slack-jawed at the open racism, from street violence to racial slurs as catchphrases in popular comedy TV shows. Euphemisms and societal racism, however, are harder to see in our own time. White Riot, through a stylised history lesson with a stellar soundtrack, and without a mention of the present day, shows us how bigotry can take root in both extreme and ‘acceptable’ ways – while providing us with an example from history of how that bigotry can be overcome.

A film as much about anti-racists as it is about racism, White Riot celebrates the bravery of the RAR founders, members and activists, musicians and artists. Required watching for any young activist, this is an attempt from Shah to actually help us learn from the history we’re so often told we are doomed to repeat. This is not my inference: we’re straight up told that ‘the fight is far from over’. Not only does White Riot present a compelling case of why the fight isn’t over, it makes you want to join in.

Watch White Riot

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.