LEAVING NEVERLAND: Gut-Wrenching Nightmare Of Abuse

I'm a student at the University of North Carolina at…

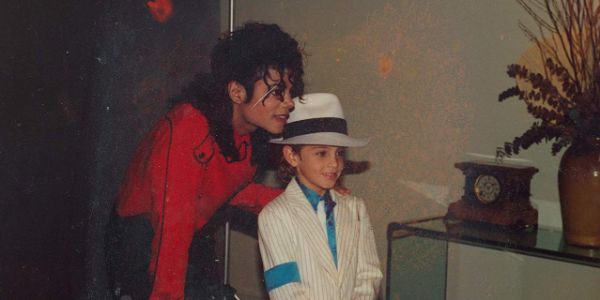

By any reasonable standard, Dan Reed‘s Leaving Neverland is a lot to handle. When viewed in one sitting, the two-part documentary runs a daunting four hours, chronicling the tale of two men who suffered horrific, unspeakable abuse at the hands of one of the most famous figures in recent cultural history. The film spares us none of the details, methodically describing how Wade Robson, James Safechuck, and their families first encountered the fantastical celebrity of Michael Jackson. They were chosen as friends by the preeminent pop star of the 1980s, given exclusive access to the Neverland Ranch, and become close with Jackson himself. It was a fairy tale. Until it wasn’t.

Reed‘s documentary is a massive textbook of information, one that is intensely specific and incredibly expansive in its portrait of both the years of abuse and the lingering effects that followed. It is not an easy watch, nor I am arguing that it should be. Yet it’s almost impossible to judge Leaving Neverland as a film rather than a straightforward primary source; its lack of cinematic flourishes has been widely discussed – and is largely the point.

Viewers, I think, will eventually have to reckon with the final product, which is both undeniably exacting and essentially a therapy session for these men and their families. Whether or not that’s the right approach is up for debate, but Leaving Neverland is a necessary work regardless.

A Predatory Celebrity

First, a bit more information on the two victims, who are collectively the film’s core focus. Robson was born in Australia, and from a very young age, he loved to watch Michael Jackson on his television. He danced and memorized all of the pop singer’s moves, eventually dazzling his family and friends with his pinpoint precision of “Thriller” and other famous tunes.

When Jackson visited Australia, Robson entered a dance-off for Jackson fans and won, which granted him the opportunity to dance on-stage with his idol. Some time later, Robson came to the U.S. and reunited with the pop star, where he was quickly welcomed to Neverland and inducted into Jackson‘s inner circle of children and yes men. At the time, Robson was 7 years old.

James Safechuck, a native of Simi Valley, California, experienced a different path to Jackson‘s world. Safechuck began in commercials, starring alongside MJ in a popular Pepsi commercial in the 1980s. Jackson immediately attached himself to his young co-star, frequently visiting his home and later welcoming him into the extravagant world of international stardom. Safechuck and his family were taken on an epic vacation to Hawaii, and they began to treat Jackson like he was part of their family. At the time, Safechuck was still a young child.

Reckoning with the Past

From here, the stories of Robson and Safechuck blur together in a way that denotes a collective experience among these men. Jackson brought children into his bedroom and closed off their parents from this world, somehow convincing everyone that his actions were innocent and playful in nature. Then the abuse started. Abuse that is spoken of in such clinical terms, colliding with the visceral intensity of Robson and Safechuck‘s narration in a way that produces horrible images in the viewer’s mind. And even after the abuse stopped, the decades of recovery meant there was still a long way to go.

With the benefit of such an extended runtime, Reed and his team span decades, beginning at the height of Jackson’s fame and continuing on well after his 2009 death. There are several individual films comfortably couched inside this brutal marathon, but Reed‘s scope and ambition never hinder his precision as a storyteller. He wants the whole picture and every horrible detail that comes with it to be brought to light; no subplot is left unexplored, no detail is excluded for the sake of concision or expediency.

Thus, Robson and Safechuck are given ample space to lift the weight of their assorted memories, from the excitement of entering a celebrity’s orbit to the horror of pushing down something so awful for so long. Leaving Neverland is absolutely about the lasting impact of Michael Jackson, but like Jennifer Fox‘s The Tale, it’s primarily concerned with comprehending the psychology of acceptance, of coming to terms with a series of events that irreversibly changed the lives of two men. The victims come first, even if the presence of the abuser lingers over the entire film.

Therapeutic Push for Understanding

But it’s also a film with no ending. Yes, Robson and Safechuck are now comfortable enough with the events of the past to share their story, but that doesn’t mean their story is finished. Among its many intelligent and heartbreaking moves, Leaving Neverland disturbingly details how Jackson altered these children in a way that goes beyond the memory of physical abuse. Families were changed, relationships were destroyed, and the pain of knowing what happened will linger long after the moment of acceptance. Several moments in the film provide Robson and Safechuck the opportunity to express their uncertainty, to cast doubt on why their parents allowed this to happen or how this abuse will continue to affect them.

The very format of the film is conducive to such open-ended questioning; Reed focuses on interviews with the two men and their families, interweaving photos and stock footage into their accounts. The nature of this formal structure makes the whole endeavor feel like a therapy session, a way of processing pain and anger and confusion through the cinematic medium. The descriptions of repulsive abuse by Jackson makes the entire film an uncomfortable and gut-wrenching experience, but at a certain point, the level of intimacy between the viewer and these men becomes a source of conflict too.

Are we learning too much information about Robson and Safechuck? Is this film nearing a point of violating their private right to process their pain? I don’t necessarily think so, but by the time Robson‘s mother is crying in intense regret, it’s hard not to feel as though we’ve been privy to something we may never have wanted to see or hear.

Leaving Neverland: Conclusion

Of course, everything about Leaving Neverland is designed to enhance the spectator’s discomfort, from the punishing running time to the unbreakable connection between the viewer and the film’s subjects. That naturally makes the experience a grueling endurance test, but its emphasis on complicity and the necessity of reckoning only makes it a more powerful watch.

In any case, it’s a difficult film to review; how do you capture the essence of something that feels like a cinematic representation of a meticulous, harrowing document? Description and analysis can only go so far, as it’s a film that each viewer must simply deal with on their own terms. Everyone will process it in a different way. But it’s a tough and incisive piece of work regardless of your final impression.

What did you think of Leaving Neverland? Did you find this to be a harrowing story? Let us know in the comments below!

Leaving Neverland will air as a two-part documentary on HBO starting on March 3.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

I'm a student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. For 8 years, I've edited the blog Martin on Movies. This is where I review new releases, cover new trailers, and discuss important news in the entertainment industry. Some of my favorite movies- Casablanca, Inception, Singin' in the Rain, 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Wolf of Wall Street, The Nice Guys, La La Land, Airplane!, Skyfall, Raiders of the Lost Ark. You can find my other reviews and articles at Martin on Movies (http://martinonmovies.blogspot.com/).