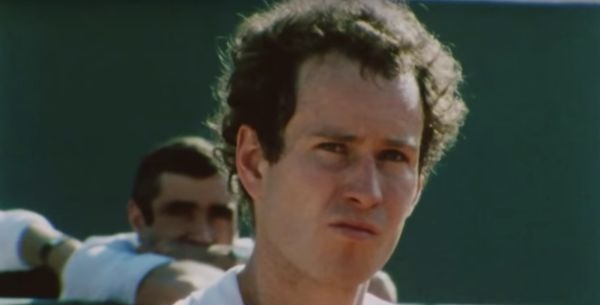

When a documentary about John McEnroe’s exploits in the 1984 French Open commences with the following quote from Jean-Luc Godard, “Cinema lies, sport doesn’t,” it tells you something prescient about where we are about to journey. There’s even a sideline cameo from Jean-Paul Belmondo. Could it be instead of Pierrot Le Fou we are examining McEnroe the Madman?

Regardless, make no mistake. This is hardly a documentary, at least in the generally conceived and the accepted sense of the word. Talking heads have been excised and the instructional films of former Roland Garros documentarian, Gil de Kermadec, have been given a near arthouse treatment. He began shooting footage on the courts in 1969, and by 1977 had become preoccupied with portraits of individuals rather than the games themselves. And looking at some of the personalities at hand you begin to understand why: Bjorn Borg, Jimmy Connors, Chris Evert, Ivan Lendl, Martina Navratilova, and certainly John McEnroe.

Instructional Film Repurposed

Though only a minor player, the filmmaker’s 16 mm footage becomes crucial to the exploration at hand. Director Julien Faraut culled the vaults and reels and reels of rushes to cut together an ode to McEnroe in an effort to understand his unique brand of success. The repurposed archival footage is subsequently turned into a bit of found art for cinephiles and tennis lovers alike.

In fact, the bulk of the material is so dedicated to the man that he remains the constant focal point as we are put courtside, almost as if he is playing a game against himself. One would think Ivan Lendl would be cast in a major supporting role and yet he hardly gets even a word of acknowledgment until the final act. The distinct focus on individual human beings and their various personal idiosyncracies could not help but remind me of Kon Ichikawa‘s documentation of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. In both cases, the results at stake are not of the greatest importance as they would be in a live telecast; instead, the human experience takes precedence.

Likewise, John McEnroe: In The Realm of Perfection has a similar preoccupation with time as Chris Marker‘s Sans Soleil. Film critic Serge Daney is called upon in length for his commentary suggesting, first of all, that tennis, unlike rugby and football (soccer), makes its own time based on the virtues of the players at its core. There is simultaneously an inherent sense of time and an invention of it that comes with each subsequent game, set, and match. Does anyone else recall the Isner-Mahut match at Wimbledon in 2010? It clocked in at a record length 11 hours and 5 minutes.

Though less expansive than its predecessor and focused intrinsically around tennis, actor Mathieu Amalric becomes the ready stand-in for the aueteuristic dialogue developed by the director in this analysis that willingly manipulates convention through spirals of time. Faraut further accentuates these factors by splicing together footage from the three on-court cameras, enacting slow-mo, replaying the same image repeatedly from varying angles, and looping sound bytes. Though we can question the purpose, aside from merely artistic aspirations, it shows this innate fascination with the vicissitudes of such a medium and sport.

An Artist on the Tennis Court

The footage is, again, unlike most anything you’ve ever watched on live television. For most of its run, it’s not about the match or the points or the rallying. It’s solely focused on the individual. In that way, it manages to latch onto not only player mechanics but an empathy that can only be attributed when we get to understand someone else on a more intimate level.

Admittedly that might be a rather odd way to describe any film documenting John McEnroe, one of the notorious bad boys of tennis but on the most basic level, it holds true. You watch his skill — the variedness of his shots — the imaginative ways to win a point and it simultaneously makes you realize the evolution of the game of tennis. A lot of the finesse of the sport has been lost in deference to brute force. Where points and matches are won from the baselines hammering away at the ball until the enemy concedes. In fact, Lendl was such a player.

An underlying trait of McEnroe is his ability to play, as they say, on the edge of his senses — forever attuned to the noise or stimuli in his accepted atmosphere. To the viewing public, it’s antagonistic, nit-picky, whatever term you deem applicable. And yet you begin to understand why those very minute details that we dismiss were so crucial to him.

In a particular sequence, we see shots of him rallying with Mozart playing over the footage because Tom Hulce in preparation for his role in Amadeus chose to view McEnroe as inspiration. The parallel is made obvious through quotation. He is vulgar but his music is not. Composer and tennis player are made alike. McEnroe even gets likened to a film director for the nominal similarities in how he chooses when to end a “scene” with the precisely placed “cut” of one of his volleys.

The central paradox of the man as an athlete is that ability to get angry, to lash out, and to seemingly lose his cool and yet generally not allow that to impede his lucidity, productivity, or his artistry on the court. That’s an extremely difficult trait to master and again it flies in the face of convention to some extent. For McEnroe, everyone was against him from his opponent to the line judges, to the spectators. And he proved them all wrong by winning.

Though it’s not necessarily an enthralling narrative, foregoing that route to be a full-fledged character study, it does culminate in the match to cap McEnroe’s run at a perfect season. He quickly took a commanding two-set lead over Lendl in the final only to falter in a five-set anticlimax. We watch it all unfold methodically. There’s nothing invariably cinematic about it. But it’s reconstructed and laid out in front of us right up until the point where McEnroe comes to the net and hits his final volley wide to give his adversary the win. He goes through the expected pleasantries and walks back to his chair totally crushed. We see it play out again and again and again from all different angles.

Cinema lies, Sport Doesn’t

I saw an interview about Borg vs McEnroe where McEnroe criticized the movie for being very disappointing. Understandably much about it was not grounded in any amount of fact. That’s where we conveniently get the “based on true events” narratives of Hollywood. My only thoughts on this project are how he would react to it. Would he take Faraut‘s film as an artsy-fartsy compliment or laugh off the exploration as pure hogwash; making connections and overanalyzing minutiae that were seemingly never there in the first place?

But the one thing he couldn’t deny is how much that loss to Lendl galls him. Even today it keeps him up some nights. Any given year, doing coverage at the French Open still aggravates old wounds. Those are the facts. If nothing else is proven then at least we can all agree the maxim holds true. “Cinema lies, sport doesn’t.”

Do you agree with the statement that cinema and tennis are both about a sense of time and the invention of time? What do you think the major differences between narrative and documentary filmmaking are? Is there a difference?

John McEnroe: In The Realm of Perfection was originally featured at the Berlin International Film Festival. It was released in the U.S. on August 22nd, 2018, and will be released in the UK on May 24, 2019.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.