IT’S SUCH A BEAUTIFUL DAY: Depression & Mortality

Kevin L. Lee is an Asian-American critic, producer, screenwriter and…

Very few films portray depression so truthfully, but Don Hertzfeldt managed to capture that and weave it together with the human condition in his 2012 animated masterpiece. Comprised of three animated shorts that, when put together, tell one coherent story, It’s Such a Beautiful Day asks for our empathy and our humble acceptance in our mortality. But it is specifically Hertzfeldt’s aesthetic and approach that gives the film its universal appeal.

Basic Animation and Instances = Universal Appeal

With the simplest stick-figure animation, the film strips away distracting details and colorful editing that would have risked narrowing its appeal. The lead protagonist, Bill, is a simple stick figure wearing a hat. There’s no color in him, no thickness in lines, no texture to his skin. He’s simply a black and white stick figure in a world full of other stick figures, a world that is intentionally bland and lifeless. But it is this very choice of aesthetic that makes Bill the most relatable fictional character in recent memory.

Any extra details to him would further narrow his appeal. An extra detail on his body would change his ethnicity, his physique, his cultural background, his religious background etc. By drawing Bill in the most basic form, he becomes perhaps the most universal character in fiction. We as an audience now have a chance to get involved with the film and apply our uniqueness into its world. We see ourselves in Bill, as we observe him.

And that is what makes his depression feel so hurtful yet incredibly accurate. In addition to making the animation basic, Hertzfeldt narrates extremely basic story beats. Most of the film consists of day-to-day activities or instances that affect Bill, and a large majority of those instances can come off as pointless, not to mention oddly specific. Things like watching ants crawl out of a sink or watching a man with a leaf blower seem oddly trivial. On one night, he dreams of a fish feeding on his skull. On one day, he stares at the manatee on his calendar.

These are all details that he may remember at that very moment but will forget about soon the next day. Rinse and repeat. It’s a stark portrait of a depressed man. Is there even a point to all of this? These droning details all pass by Bill as his health begins to deteriorate. We learn he has a fatal mental disorder, but we are just as confused as he is. That is because we are not always observing Bill. Sometimes what Bill goes through, we go through.

A Chance to Self-Reflect

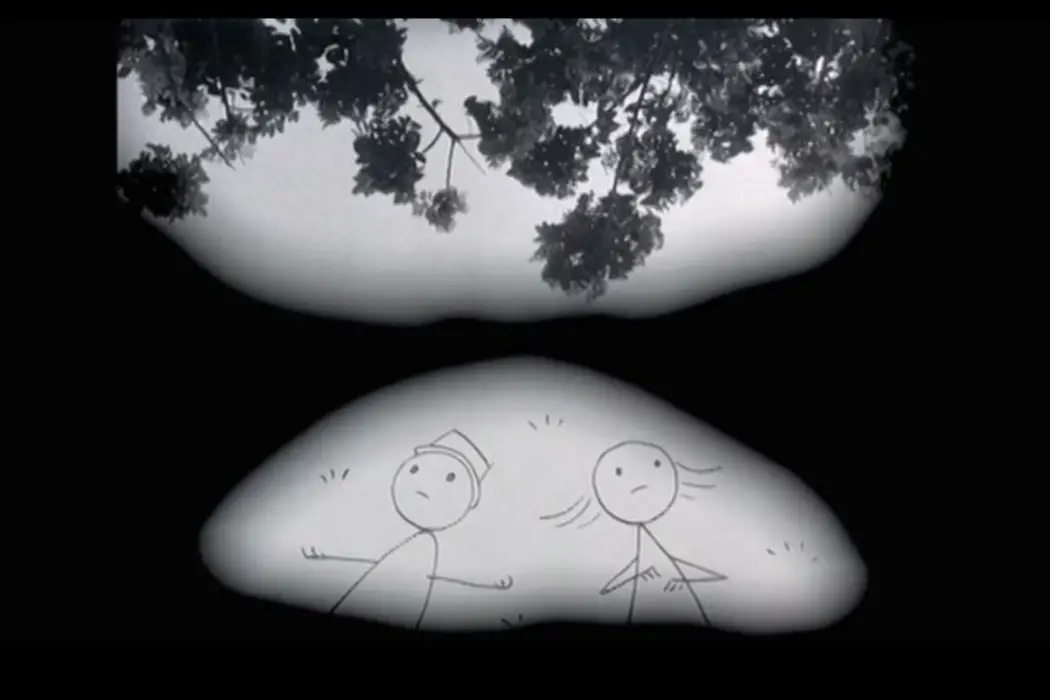

In a sense, the film breaks the fourth wall on multiple occasions. At times, we are given narration about Bill’s experiences, as if we’re an observer. At other times, the very medium and film strip will distort, go jittery, and implant random visuals into the frame, as if we are experiencing what Bill is experiencing. As moments of Bill’s life, both the physically mundane and the psychologically hallucinatory, slip away from him, we are offered a chance to self-reflect on our lives.

Though Hertzfeldt successfully weaves in some dark comedy to keep us invested, we ponder over the emptiness and absurdity of life –that pointlessness and lack of meaning in living, where every single detail you notice every day is something you just shrug off and forget about the day after. Or even those details that shaped your life that are out of your grasp because your mind and your body are no longer in unison, and all you’re left with is incomplete, unexplained emotions.

Hertzfeldt implants this emotional confusion onto us via Bill’s medical tests. We hear other human voices ask if Bill can describe the images shown to him. But the images are shown to us on the screen. And like how Bill might see them, we see nothing but distorted, incomprehensible nonsense. Pieces of pictures that are so close to coming together to form a complete memory but are fragmented enough for our answer to potentially be wrong.

It is here where Bill is told he has little time left to live. It is also here where Hertzfeldt’s inner workings converge, and we realize that this whole time he is using Bill’s illness and mortality to explore the cosmic –that Bill is a vessel for humankind, and the film is a contemplation on humankind’s relationship with a chaotic, indifferent universe.

The Beauty of Mortality and… Immortality?

But it is this execution where the film also captures the beauty of life in general. As Bill is trying to make the most of his last few weeks, the film shifts in format. Suddenly, the dull black-and-white drawings become live footage with real color. Suddenly, the vignette windows that permeated throughout Bill’s life has opened into a new beautiful world that he has never seen before. Suddenly, the walk he has always taken his whole life is this eye-opening out-of-body experience.

And our sadness for Bill becomes an enlightened joy. The world is beautiful because it’s imperfect, clumsy, colorful, textured, and cosmic. We are beautiful because we’re temporary. Or is Hertzfeldt suggesting something otherwise?

The ending of It’s Such a Beautiful Day is an unforgettable montage. Told almost like in a dream, a rejection of death, the ending is Bill’s experiences as an immortal. Time and death is forever a stranger to him, as he learns everything there is to learn. He reads all the books, learns all the languages, and travels across the entire world. He becomes one with the universe. He becomes infinite. But is Hertzfeldt painting this as a beautiful thing or a satirical statement? Does immortality really render our humanity meaningless?

The way the film shows Bill’s immortality is undoubtedly one of beauty and one of tragedy. There is something enlightening and meaningful to be like a prophet in your world, especially if you use your immortality for the betterment of the world. At the same time, there is something desperately lonely and gloomy about living forever.

As we ponder over these existential questions, there is perhaps one agreement we can all come to: It’s Such a Beautiful Day is one of the most universal films ever made. By employing simple fragile stick figures and voyeuristic vignettes, Hertzfeldt has created an intimate, bizarre, yet relatable universe. The end result is an authentic depiction of depression, mental illness, and a poetic meditation on mankind’s relationship with the universe.

But the ending is so open-minded that I must inspect further. Maybe, at the end of the beautiful day, it all boils down to what matters most to each and every one of you out there. And so I must ask the reader:

Would you ever choose immortality? If the answer is somehow yes, is it because you want the perks of life, or is it something Bill pursues in the film, like knowledge? Are you answering these questions for yourself or for something bigger, like for mankind?

It’s Such a Beautiful Day was released on 24th August, 2012.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Kevin L. Lee is an Asian-American critic, producer, screenwriter and director based in New York City. A champion of the creative process, Kevin has consulted, written, and produced several short films from development to principal photography to festival premiere. He has over 10 years of marketing and writing experience in film criticism and journalism, ranging from blockbusters to foreign indie films, and has developed a reputation of being “an omnivore of cinema.” He recently finished his MFA in film producing at Columbia University and is currently working in film and TV development for production companies.