Melbourne Queer Film Festival 2019: Interview With 1985 Director Yen Tan

Alex is a 28 year-old West Australian who has a…

Yen Tan’s stirringly soulful drama 1985 is finally making its Australian premiere at this year’s Melbourne Queer Film Festival, where his two previous features, Pit Stop and Ciao, also made their Australian debuts.

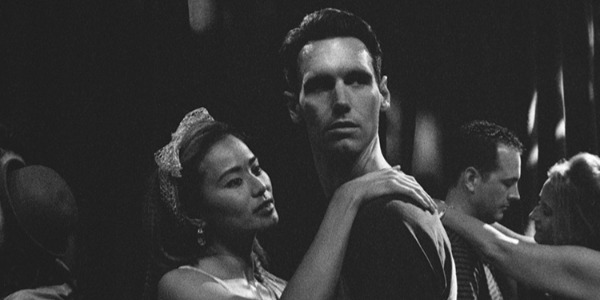

Delivered in an appropriately stark black and white 16MM film aesthetic, 1985 tells the story of Adrian (Cory Michael Smith), a lawyer who has returned to his Texan hometown at Christmas during the titular year, burdened with a painful announcement that he struggles to deliver to his conservative parents (Michael Chiklis and Virginia Madsen). Reconnecting with the place and people that he abandoned when moving to New York, Adrian slowly comes to terms with his new reality, one which presents a scary but ultimately hopeful future.

I had the chance to talk with Yen Tan, the film’s writer and director about his new film, the decision to shoot on film, the realities of low-budget film-making and the current state of queer cinema.

Alex Lines for Film Inquiry: 1985 is based off your short film of the same name from 2016, so when was the decision made to expand it into a feature, and what were the challenges of doing so?

Yen Tan: The feature was written up pretty quickly after we made the short film in 2016 so by the time we premiered it at a festival, I already had a first draft for the feature. We developed it for a while and the feature didn’t go into production until 2017, between the short and the feature there was roughly a year turnaround which for my experience, seemed really fast.

Challenge-wise, it was along the lines of financing, we didn’t make the easiest kind of film, not only because of the subject matter, but also aesthetically black and white so it wasn’t really an enticing package for people to want to put money into. A good thing is that we did it for very little money, with very limited resources, thankfully we got a really good cast so it all came together.

In a way that was in the spirit of the film – living with HIV/AIDs in the 80’s you’re not getting enough support – you’re not getting enough of anything, making the film was like that too, which had a sense of poeticalness to it.

Dating back to the short, what was the inception of this story?

Yen Tan: In the 1990’s, one of my earliest jobs after I graduated from college was in the life insurance industry. I was interacting with a lot of men who were living with HIV/AIDS, so at that time I was in my early twenties and I was hearing a lot of stories about what their experience in the 80’s was like.

For me, it was interesting to learn about what they went through because they come from a different generation, it was very sobering to hear about how bad things were. I also thought about, on a personal level, what the epidemic meant to me growing up as a kid in Malaysia in the 80’s, where there was a sense that it was always a very sensationalistic thing, when AIDs was talked about in the news, and I think there was a lot of misinformation.

I remember in 1985, I was ten years old and I was having the inclination I was gay, I just assumed that being gay meant it was going to come with AIDs, that there was no distinction between the two things. So I think making the film, both the short and the feature, was a way of unpacking, not only telling the stories of this lost generation of people – a lot of them who are not around anymore to tell us their stories – not only was it an opportunity to shed the spotlight on those stories again, but it also was another way to tackle, on a more personal level, how the epidemic directly impacted me.

One of the film’s most striking elements is its monochrome cinematography, which for me gave the film a timeless quality; what was it about this look that interested you?

Yen Tan: I’m glad you said the word timeless, because that’s one of the biggest factors for it. I don’t necessarily think I’m breaking new ground in terms of the story I’m telling, I think what I’m trying to do is tell a very familiar homecoming story about someone coming home and not telling their family what’s going on with them.

This is very familiar, and the characters are seemingly familiar, but then you learn who they are over the course of the film, and as you peel layers off them and the story, you sort of have an idea of what’s really going on as it progresses.

I think visually I’m trying to do the same thing where black and white is not the most obvious choice for a movie like this, which was precisely the reason why we were drawn to it, because it’s not the kind of story you think of in terms of black and white. That’s what made it interesting, an unconventional way of telling the story visually that also, from a creative standpoint, made a lot of sense because I felt like those were very stark days for people who experienced the epidemic. I think they remember those days in very stark ways, and black and white was the right way of representing that experience.

It was a nice change to the current trend of 80’s nostalgia, where everything has to be this neon-lit throwback littered with identifiable cultural artefacts.

Yen Tan: Oh sure, it was one of those things, even though the film was called 1985 and there’s very specific 80’s albums used, we didn’t want to make it nostalgic because the point wasn’t about drawing your attention to the setting or wardrobe.

The colours of the era wasn’t something we were interested in doing, black and white has a way of diffusing all those elements, and just quickly narrows your focus to the characters.

And it was shot on Super 16MM Kodak film, so for a low budget film, was this a challenge on a production level, and was there ever the temptation to shoot it in digital?

Yen Tan: Yeah, there’s definitely very specific challenges when it comes to shooting on film, you sort of run into situations where you realise about the quality control on equipment, especially for a low budget production. We’re not a Christopher Nolan production, where those people get the top shelf of everything, and then for us, we have to play within the limitations of shooting in that format, it’s occasionally hair-raising, in the sense that we don’t know what’s going to happen until we get the film back and there’s always a fear of the footage being damaged or lost during delivery etc.

Then there’s the idea that there’s literally no backups, you’re not backing it up onto a hard-drive, there’s definitely things like that I don’t like about shooting on film. I felt like it worked in favour for us though, because I think it’s something in the aesthetic, it’s something we’re not used to seeing anymore: this grainy 16MM aesthetic in black and white, which feels very alive because something is always moving in terms of how the grain moves in the image.

I think that brought a level of commitment to the cast and crew as well, because most of the time people don’t want to work on film anymore, so when they get on a film set, they realise that every time we start rolling, it’s real. There’s more at stake in other words, for the actors I felt like it gave them this pressure. For the most part we weren’t shooting a lot of takes, so they have to nail their performances, and they did that. It worked in the favour of a small production like ours because it’s not like we have a lot of days to shoot, so we have to keep going, which helped us save money in that way I guess (laughs).

One specificity I noticed in your script was that, especially in the final exchange between Jamie Chung and Cory Michael Smith, that the terms gay, HIV or AIDs are never used. I wanted to ask if this was a deliberate choice, and if so, what were your reasons behind that?

Yen Tan: Yeah, so it’s definitely deliberate, because 1985 was the year where President Reagan said AIDs for the first time. It was something in the zeitgeist for a couple of years but never talked about publicly, so I think not saying the words HIV, AIDs or gay in the film was very appropriate because I think that’s the kind of world it was.

Those words were just so taboo, with such a deep-rooted sense of stigma, that those were just things we didn’t want to talk about, our whole thing was to keep those things off-screen. Obviously in the conversation between Jaime and Cory you lean forward because that’s the section where he tells her he has AIDs, so we intentionally leave those words out because we also were confident that the audience knows the context, I think that’s the benefit of making a film about AIDs in 2018, because we don’t have to tell you what happened anymore.

We don’t have the burden of educating the viewers anymore, we just assume that the words that we’re leaving out are at the back of your mind when you’re watching it.

Speaking of the script, whilst it slowly peels away the layers of the archetypal American family of that time, the backbone of the story lies within the dynamic of the two brothers. Was this an important element for you when originally crafting the story?

Yen Tan: Yeah for sure, for a film like this, it’s very easy to turn it into this rabbit hole of melodrama where things just get worse as you watch it, which forces you to ask yourself why I’m watching this sort of film that’s really depressing me, if it’s not giving me any sense of hope.

Having the brother was a way to look into the possibilities of what that means if say, your interpretation of the film was that the brother was gay, of what does having an older brother who is gay means for him as he grows up. That was an angle that I specifically wanted to tackle, because I felt like the younger brother is essentially my experience of growing up, and what AIDs meant to me from the point when I was a kid to when I became an adult and learning that it’s two different things, and there’s a distinction that you can be gay without being weighed down by the baggage of the epidemic.

I thought it was important to infuse that within the film, because especially at the end, when Cory’s character leaves the tape message for him, it’s the part of the film where I’m tying the past and present. That’s the takeaway from all the horrible things of the 80’s and 90’s: ultimately all the good things we have today, all the progress that’s been made – marriage equality and whatnot – all came from this very specific point in the history of AIDs activism of the 80’s, a lot of the privileges that we have today came from these bad days.

This film premiered nearly a year ago today at SXSW, and has had a pretty successful festival run at both general and LGBT film festivals, and I feel, between this and a lot of films I’ve seen at festivals lately, there’s definitely a shift in mainstream acceptance of queer cinema, especially with the recent runs of Call me By Your Name, BPM, The Favourite, and Bohemian Rhapsody, what’s your viewpoint on this shift?

Yen Tan: I think it’s a shift that comes and goes over the years, I think back in the day when Brokeback Mountain came out it felt like the tide was changing, so I think we’re going through another phase of that, I don’t think it’s something that’s ever going to go away.

I mean right now I think we’re moving into another level of conversation about queer cinema, It’s interesting that these days we’re very rapt into identity politics, and there’s a lot of conversations about who gets to tell whose story. It seems that this day if you’re not queer and you tell a queer story, there’s going to be challenges ahead you know, that people want to hold you accountable for these things, and you have to relearn how to articulate your creative intentions, otherwise people are just going to shit all over you.

I just talked about this recently also, when the actor Ben Whishaw said at the BAFTAs that he wants gay actors to get straight roles too, gay actors getting gay roles and straight actors getting straight roles, and I think what he means there is something I’d like to see happen. I’d like to see this next stage of queer cinema where there’s equal opportunity across the board, in other words, queer artists can tell non-queer stories, as much as non-queer people can tell queer stories, this sense of even-level field.

It always seems nowadays that queer people can’t tell their stories whilst non-queer people can, so until we get to the point where it’s equal, I hope that’s what we’re aiming for.

I think a major breakthrough for that was Barry Jenkins’ success with Moonlight.

Yen Tan: For sure, all these things have to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, because I think it’s very narrow-minded to say that you have to be this person to tell this story, for instance, I could’ve been thrown under the same bus, people can accuse me of telling an AIDs story when I wasn’t directly impacted by it.

But I still feel like I added something interesting to the dialogue, and I’m not denying that, yeah I didn’t live through it, but I experienced it from a different vantage point and this is what I’m adding to the dialogue, I’m not taking up anyone’s space, I’m just adding something to the table.

Film Inquiry thanks Yen Tan for taking the time to talk with us.

1985 is currently available to rent/buy on Digital in the US, and will playing this March in Australia at the 2019 Melbourne Queer Film Festival, details for sessions can be found here.

1985 will be released theatrically in Australia through Icon Productions on 25 April.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.