Melbourne Documentary Film Festival 2019: Interview With THE GHOST OF PETER SELLERS Director Peter Medak

Alex is a 28 year-old West Australian who has a…

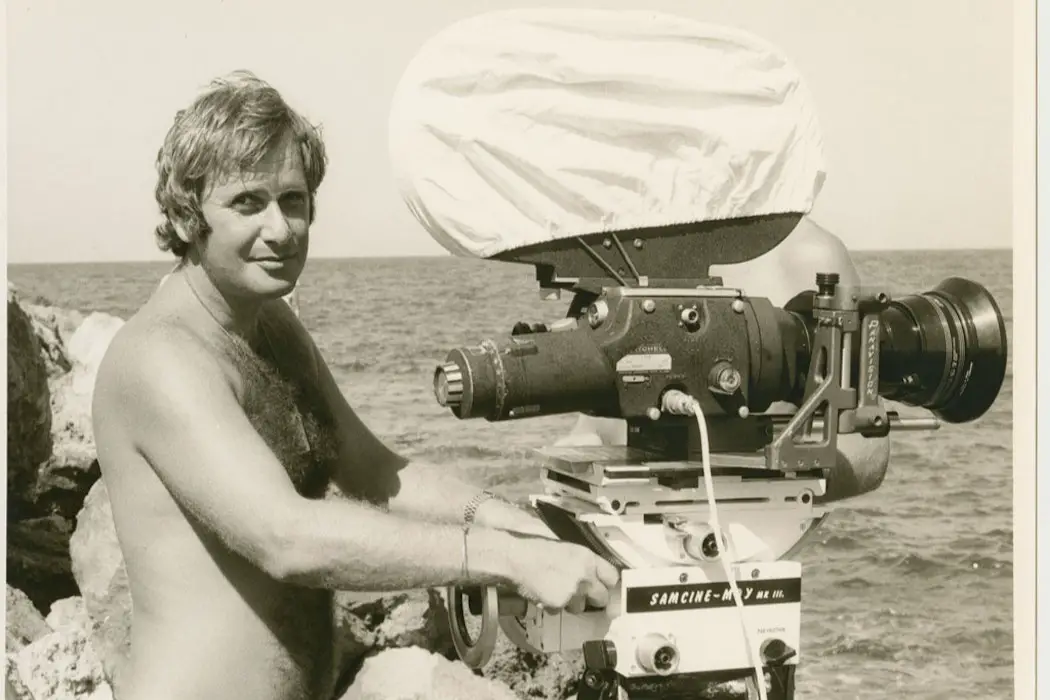

Pick any decade from the past sixty years and Peter Medak is guaranteed to have made at least one classic within it. The Hungarian-English filmmaker, who now resides in Los Angeles, made his fiery debut with Negatives in 1968, which was immediately followed up with A Day in the Death of Joe Egg in 1972, the same year as the first film to put him on the map: The Ruling Class, which scored Peter O’Toole his fifth Oscar nomination. If we went through the next four decades, we’d discover the George C. Scott horror The Changeling in the 80’s, neo-noir Romeo Is Bleeding in the 90’s, the infamous “ATM” episode of Breaking Bad in the 2000’s, and now for the 2010’s we have The Ghost of Peter Sellers, a contemplative documentary that has Medak reflecting on the one film that nearly derailed his entire career in the 70’s.

Peter Medak’s poignant retrospective on his failed 1974 Peter Sellers pirate comedy Ghost in the Noonday Sun, is not only a captivating rundown of what went wrong, but is also a touching meditation on reconciling the past, and what it means to define ourselves through our failures. The Ghost of Peter Sellers, much like the recent Lost Souls – which detailed Richard Stanley’s disastrous 1996 making of The Island of Dr. Moreau – has Medak revisiting the people and places that were involved in the botched production of Ghosts in the Noonday Sun, with most of his interviewed subjects giving the same common answer – Peter Sellers was an absolute nightmare to work with.

In 1973, coming off his trilogy of independent successes (The Ruling Class being the major one), Peter Medak was handed his first major project: A $2M production of Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan’s latest collaboration, a sweeping 17th century comedy that would shoot in the sunny seas of Cyprus. It all sounded perfect, but problems arose from practically day one; the script was regarded as terrible by everybody, the complications of shooting on sea caused frequent technical difficulties and constant bad weather lead Sellers to quickly lose faith in the director – even attempting to stage a mutiny to kick him off. Even the late arrivals of Seller’s close pals, Spike Milligan and actor Anthony Franciosa, failed to resuscitate the collapsing project.

Despite the amount of uncontrollable environmental and technical accidents that befell him, Medak took the failure at heart – the film was finished, but it was considered so bad that it was shelved by Columbia Pictures, and Sellers attempts to buy it back and re-edit it proved to be too expensive. Despite his erratic behaviour – including faking a heart attack to leave set – The Ghost of Peter Sellers beautifully allows the guilt-ridden director to exorcise his demons; against himself, against Sellers and against the film itself, within this surprisingly eloquent contemplation of a well-intentioned misfire.

After I watched the film as part of this year’s Melbourne Documentary Film Festival, I had the chance to talk with the legendary Peter Medak about his new documentary, reconciling the past, his many friendships with some of Hollywood’s best, how he handles his actors and how he met Cary Grant through a car accident.

Alex Lines for Film Inquiry: Can you tell us how The Ghosts of Peter Sellers began for you?

Peter Medak: Oh my God, it’s a long story but I’ll try to make it short. I did Negatives with Glenda Jackson, A Day in the Death of Joe Egg with Alan Bates and then The Ruling Class with Peter O’Toole. Ruling Class was an United Artists movie and Arthur Krim, who owned the company, loved Ruling Class – which got Peter nominated at the Oscars and at Cannes, which was my first experience at Cannes – But Krim said, look, this is your next movie: I want you to do this film called Death Wish. I wanted to do it with Henry Fonda because it was about a 65-year-old accountant who takes the law into his own hands.

And it wasn’t the Charles Bronson character – I thought he was wonderful in it – that was my take on it. So not Krim, but David Picker, who just recently passed away, who was the head of production at UAA said, look, unfortunately I can’t do it with Mr. Fonda because we don’t think it would make for a commercial movie, but you can have whoever you want. And I said, look, I promised Mr. Fonda that I would only do it with him if he reads the script and likes it – which he loved it.

So I, in my great wisdom, walked out of the movie and went back to London the following weekend. I bumped into Peter Sellers at King’s Road and we had the same agent and he said, I just heard from Dennis, you walked out of your movie. And he said, that’s terrible for me, but it’s great for him because you can come and do my pirate movie. And that’s how it began and I said yes to it on Kings Road – and that’s how the whole saga began.

Peter was a great friend who I love and the rest of it is what the movie’s about. I didn’t want to do it because I didn’t want to make a film about trying to say that Peter did this and that, but at the end I decided to do it because I thought it was better to do it and have a record of it and to talk about the 70’s of London and Peter and Spike and that whole period of London and English movies at the time. I could somehow explain, – not to defend myself – but it wasn’t really my fault that the whole movie went the wrong way around, it was a total disaster and which I was blamed for by revenge because as I keep saying it throughout the whole filming, how much I love Peter and even though the terrible things he was doing to me and everybody else, he just sometimes wasn’t in present time.

And it’s unexplainable because nobody would understand that this is the brilliance of his performances. Everybody who had worked with Peter had the same experience unfortunately, including Blake Edwards. I don’t have the medical reasons really for it, you know, people weren’t aware of it at the time. Anyhow, I made the movie and I’m very happy to have been able to make it, It took us about three years, if not four on and off. It started with my wonderful producer Paul who came from Cyprus out of the blue from the Internet, who had nothing to do with movies, but now of course he’s obsessed with films.

It was a marvellous experience doing it because it took me back to Cyprus where I never wanted to go again and I walked the same footsteps where I was shooting and certain things happening with Peter and that’s how the movie came about. The wonderful thing is that I didn’t write a word of it, I just did it from my heart, I think that’s maybe why this movie has this energy about it, it’s full of interesting information about all those crazy times – that’s how it really came about, you know, and I felt the presence of Peter and Spike throughout the whole movie, I think they were definitely there with us.

This film is quite an emotional and literal journey – did you start with a formal structure in mind?

Peter Medak: No, I didn’t at all, I mean, I was just really following my memory of it all. I originally wanted to start it in front of United Artists today, which is not UAA anymore, and I was going to walk out to the camera through the front door of the same building, saying this is where I walked out of what probably would’ve been my most important film. And then try to start the story in front of that building in New York and then go to King’s Road and then to Spike’s office. But the structure really came about me talking about it obsessively over the years with all my friends who knew me or all the writers of scripts I was working on, you know, when you sit together for three, four, five months, all of your stories kind of unfold.

With Gary Oldman, when we did Romeo is Bleeding, Gary knew everything about it. It was in fact Gary who said to me one day, you were bloody crazy, we should make a movie about the making of The Ghost in the Noonday Sun. We tried to develop two drafts of the script but unfortunately we never did it, but it was Gary that said that he didn’t want to play Peter Sellers, he wanted to play me! And then we should get somebody else to play Peter. Gary has actually seen this movie and he was absolutely blown away. He watched it on his own and he said, I just couldn’t believe it, it’s amazing, but I hope to God now you can forget about it.

I don’t know if that’s the case. I mean, it’s not that I’m obsessed with it, but because it was so funny and, people wanted to know about it. That’s how the friend of mine, Simon van der Borgh, who is walking with me came in, because I realized early on that it will be terrible, just first of all, I’d never realized until maybe two weeks before shooting that I have to be the central part of the film. Because I’m the only one who knows what happened, then I saw that it could get incredibly boring if it’s just me.

So I wanted Simon because we were working on another script about Napoleon and consequently I had told him about everything that went on in the film, so I asked him if he wouldn’t mind coming to London, going to King’s Road, then I don’t know what will happen, but let’s just see. It was wonderful because it does add that I can talk to somebody or somebody can talk to me, instead of just directly explaining everything.

I feel like it’s a nice framing device, because he brings up a lot of questions that I feel like the audience wants to ask.

Peter Medak: Yeah, absolutely. He brought some wonderful contributions to it as a writer, but sometimes we got angry at each other. I mean, I love him, but you know, sometimes I said, why is he asking me these questions? Because I don’t know if I should really answer them, but then I did and it was wonderful because it brings with it a whole bunch of other incredible goodness.

I think it’s the reason why the project has vitality, because we didn’t calculate or plan every second of it. Wonderful things happened like that doctor turning up, who was in fact the guy who wrote out the medical certificates for Peter, who I hadn’t seen since 1973. So that’s why I kept thinking, it’s bloody Spike and Peter doing it.

Now that you’ve made it, have your feelings changed towards the film and the experience of it all?

Peter Medak: Well, it’s hard to tell. I mean, it’s wonderful to have 92 minutes of it, but it will never go away. None of my other experiences on movies ever go away because they stick with you for the rest of your life. It’s like if you were to write a book or something, it’s because you drove so deeply from yourself and from other people and your experience together. That’s what makes my life – or other director’s lives – so rich because it never goes away.

Philip Kaufman, he saw the movie and he sent me an email that said that he started crying at the beginning of it. He said that the wonderful thing about it is that you’ve made a movie about not just about you and your experiences, but you made a movie about all of our lives as directors.

Terry Gilliam had the same response because of The Man of La Mancha. I wasn’t copying his thing at all, we’ve known each other for many years, I knew all the Pythons because they were such admirers of Spike Milligan and The Goon Show. They all knew each other and there’s no secrets and it was a completely honest reaction. That’s incredibly gratifying for me, that other directors whose work you deeply, deeply loved over the years, exceptionally brilliant American and English directors, could share it, and because I didn’t want it to be a self-pushing exercise, I had to be there in it, there was no other way.

One of the elements of the film that I wanted to ask about was the casting of Peter Boyle, how was your time with him during the production?

Peter Medak: Peter Boyle was lovely, but we were friends before. Ever since he made that wonderful movie years ago and I can’t remember how we met, I think we met in London and we became very, very good friends – I used him a couple of other times, I used him in Species 2. God, what was that famous movie of his, that started his career?

Joe?

Peter Medak: Yeah, I think it was that movie, that’s when I met him, then we became very good friends. I remember going to Roman Polanski’s birthday because Roman was a friend in London, I remember Nicholson and Polanski and Tony Richardson, standing in the kitchen on his birthday party – I remember that Deep Throat was on in every room of the house. Then there was this chance where John Heyman needed an American name and Peter agreed to do it. It was a fairly small part of the film, but we were great friends so that’s why he agreed to do it. I loved him and I loved his work and we stayed friends for many years until he passed away. The same was with Anthony Franciosa, I met him in 1963 when I came to Hollywood for the first time and I was on setting up some television production and Tony was starring in it.

I loved Peter, he had this wonderful, crazy quality and I was around when they were doing Young Frankenstein. I wanted Mel Brooks to be in this, because he was a great friend of Peter, but he couldn’t do it. All kinds of other people were going to be in it, but there was no room anymore after 92 minutes, it was hard to cut down. So you’ve seen this at a festival in Melbourne?

Yeah, as part of the Melbourne Documentary Film Festival.

Peter Medak: I was just with Fred Schepisi, he’s a great friend. He was leaving today to go back to Australia, he’s seen the film too and loved it. It’s nice to have friends that want to see it.

Was there any projects that you lined up that you lost due to what happened?

Peter Medak: Well, there was like 5-6 films. There was movies with Rod Steiger, with Richard Burton, one with Sean Connery called Our Next Man. Very much because I suffered and punished myself for what happened on the set of the movie, I didn’t want to make the same mistakes, so I’d undertake some projects which I was interested in, work on them for quite awhile and at the 11th hour I’d say, I can’t do this because they’re not giving me what I need and I can’t make another f*ck up. Because of that, I walked out on all these movies, which I should have made and it was crazy not to do them – some of them were quite important.

And they got made by other people?

Peter Medak: Yeah they were all made, the Burton movie was made, that was at United Artists then and Never Promise Your Rose Garden, which I was going to do with Charlotte Rampling and Mick Jagger was gonna play a fantasy character in it. I’d just find reasons of walking out, it kind of continued throughout my whole career. Because it gets so embedded in you, it affects your thinking in a way, clear thinking, in order to protect yourself and the minute you see the signs of not liking the producers or that people are lying, or they won’t give me the location, it used to be my mania that it’s my responsibility to my actors, to protect them. Because they said yes to make the film, knowing that if I’m going to direct it, I’m gonna do my best to make the best possible thing.

But this continued throughout the rest of my career, this kind of madness of self-protection and the protection of everybody else, because of the guilt of not having been able to live with this thing. That whole section in the new documentary about trying to explain where this is guilt comes from completely came unconsciously, when I was talking about the Second World War and this and that.

It really started from a recording, not even from shooting, with my lovely editor, Joby Gee, who was asking questions and when we first cut it into the film, I said, no, no, no, can’t do that. I can’t put my personal life into that, that doesn’t make any sense. Then everybody started persuading me saying, don’t change anything. And I said, am I swearing too much? Am I being too emotional when I’m tearing up? I said, it’s soppy, I don’t want it. Walter Murch, who was this great editor, who has seen the film in various cuts, said don’t lose any of that, that’s what makes it work.

As a director, you’re in the dark, particularly when you’re talking about yourself, it’s the last thing you want to do. Actors hate to watch themselves on the screen. As a director, we’ve never acted, you’re not an actor, you cringe about it, you know? I mean with Peter O’Toole, he saw a little bit of his dailies at the start, then he didn’t watch any of it afterwards because he knew what we were doing was great.

They hate watching themselves, they’re like f*ck, that looks terrible etc. But I’m incredibly grateful and lucky to have the experience of working and getting to know these incredible actors, it’s really a director’s job to protect them and nurture them and give them everything so that they can function. Doesn’t mean you let them get get away with murder, but they’re just magical creatures, actors and I love them and they know how much I love them because they can see in my work, whether they like the movies or not.

After this film you’ve got to work with George C. Scott on The Changeling and Gary Oldman on Romeo is Bleeding, did your time with this film ever create a hesitation to work with prominent actors like this again?

Peter Medak: No, not at all. Because those big actors, they’re all just actors. Great actors, you know, but once you start your first movie with Glenda Jackson, you know. [laughs] How brilliant can it be to work with Peter O’Toole, Alan Bates, then Peter Sellers, George C. Scott, Gary Oldman and then Bryan Cranston, it’s the cream of the best of the best. They’re the greatest people to direct. I mean, George was a piece of cake, he was easy.

And everybody said he’s so over-powering etc. but you have to risk everything and you have to risk yourself and what you get back in exchange, is the the trust of these actors. Then they feel safe and they’re prepared to do whatever you want them to do. It takes two or three days at the beginning of the film to establish that mutual trust in each other, but once you have that, it lasts for a lifetime. That relationship goes on forever, whether you work together again or not, you know? It makes you as rich as a billionaire, because you are walking in each other’s souls. Such an intimate relationship between an actor and a director.

The Ghost in Noonday Sun was eventually released on VHS in 1985, and DVD in 2016. How did these releases come about, and what were feelings about it?

Peter Medak: I didn’t even know. You know, it came from John Heyman, David’s Dad, who is an amazing business man and it’s probably because he felt that the whole thing was a lost cause and the film was a disaster. If he puts it on DVD, maybe they can make some money or I don’t know why. I didn’t know about it, I only found out about it when I saw this poster [which is hanging in Peter Medak’s room] which was for the DVD, but the transfer is very bad. John made a new copy of it for us to use in the movie and it’s absolutely phenomenal, the beautiful photography of it. I think it was just an item thrown out onto the market.

I’m glad he did because again, it exists and I’m hoping, the dream would be that if the documentary succeeds on some level, but maybe there will be a chance to release their original movie and the documentary together on Criterion or something like that. I’m hoping that if it really has some muscles, then that will probably happen because it would be very easy to do because, John Heyman’s estate owns the movie, it could be very easily arranged. I’m glad it’s out there, as we all love movies so much. It’s like Tarantino screaming out in Hollywood Boulevard when he was filming his last movie, and everyone’s staring at him as he’s going, “We’re making a movie!” That’s what it’s all about.

That’s funny that you bring that up because I feel like with that movie [Once Upon a Time in Hollywood] coming out soon, especially with someone like you who got to meet him, that there’s going to be a lot of questions about Roman Polanski and that time in Hollywood.

Peter Medak: Yes, I’m sure there will be. Oh Roman, it’s a very tragic and difficult subject. I was around at the time and I knew Roman very well – we still know each other today – it was a terrible, devastating thing for everybody. To live through something like that, you’ll never be the same again.

What period of Polanski’s career did you meet him?

Peter Medak: Oh God, well I was fortunate to be under contract for Universal. I got to England in 1956, barely speaking English. In 1963, having gone through the film business with this and that, I was offered a contract from Universal for seven years to come onboard to direct television and then go back to England and work for them. And Sid Sheinberg who later on was the mogul of the studio, was a lawyer at the time and I become his responsibility, he picked me up at the airport and brought me to Hollywood.

I went to this party in ’63, at the time of the Oscars and Knife in the Water was nominated and that’s where I met Roman at that party in Malibu and we’ve known each other ever since – and of course that movie won him an Oscar. Then I moved back to England eventually, after 3-4 years and then at that period of time Roman was living in London, where he made Cul-De-Sac and Repulsion and The Fearless Vampire Killers.

We knew each other, we used to go to the same one and only club in London at the time. That’s why I could make such an incredible documentaries on that period because I was there. The club was called the Ad Lib, I was there one night, sitting with Walter Shenson, who was the American producer of A Hard Day’s Night. And I’m sitting with Walter and he said, come on meet the boys, and that’s when I met the Beatles.

Two days later, I’m at the same club, sitting with another friend and there’s the four guys sitting there with their funny haircuts and all that. And I said to the friend, do you know who those guys there? I said, they’re the Beatles! And he said, they’re not the Beatles, they’re the Rolling Stones! I mean everybody knew everybody in those days, it was an amazing period.

There’s some wonderful things films being made about it, but my memory of London at the time was just fantastic. The other thing I would love to do is do a documentary film about my arrival to England in 1956 from the Hungarian revolution. And not have it be about me, like The Ghost of Peter Sellers, but through me to see what it was like London in 1956 and what England and the English was then. And how life had began from a total disaster and how it happened that a few years later I’m suddenly in Hollywood. It’s not about that, it’s not about Peter Medak but moreso what happened, because it’s a vanishing world, you know?

What did London look like? What did that refugee camp look like when we first got here? How did we get to London? It’ll be a fascinating journey because it talks about England and the English. Particularly with today because everything is so questionable on both sides of the world and nobody knows about is going on. But to look at those wonderful, good old days of England and their traditions. But I keep telling everybody about it because I’d love to do that. It would be incredible because all this footage exists of the refugees arriving in Heathrow Airport in 1956 December, all these crazy scenes, and it’s not about Peter Medak, but everyone who went through it, and how they all got started.

I find that time period in Hollywood so fascinating.

Peter Medak: It’s just a lot of people who love movies. The experiences that I’ve had with all these incredible actors that I’ve met and gotten to know, even the people I met at Universal, when I was here, not actually making anything, but just meeting them, you know, from Cary Grant and beyond, you learn that they’re not just stars, they’re also great actors.

When I met Cary Grant, he backed his Bentley into my shitty $300 car. I was asked to come to his office and he said, I’m just curious as to why you parked in Dorothy Styne’s spot? Because Dorothy was Jule Styne’s sister, so I said, because she’s a friend and she’s never at the studio, so when I’m late and in a hurry, I park in front of the studio and Mr. Grant said, well we have a little problem.

He said, because I backed my Bentley into your car, my car’s fine but your’s isn’t, so that’s how we met. He then asked me, where are you from? And I said, well, I’m English and he broke out laughing and he said, you’re English? You’re not English, I’m English, My family lives in Bristol! From that point on, we stayed friends. For years and years, I couldn’t believe I was friends with Cary Grant, looking the way he looked in all his movies and he’s also just an actor, but he was wonderful. Those experiences were wonderful, like when I watched Mr. Hitchc*ck direct on Marnie, I was getting my work papers sorted out, so I couldn’t do anything, so I just watched. Sometimes it feels like my life is a Tarantino movie.

What was it like to talk to Hitchc*ck?

Peter Medak: Yeah, he was amazing, had a very pompous English accent, “good evening and morning and all that”. Every frame of every shot was drawn out on these huge, not blackboards but probably the size of an art table. He spent like a year drawing out every shot, every scene with the exact camera angles – 45 degrees or a 40 lens for example – but he was an incredible technician.

And you learn so much just by watching them. You don’t copy them, you can’t copy because then you won’t, remember any of it, but study the way they handle the actors and talk to them. I always love talking quietly to my actors, whispering in their ears and all that. I have this great friend of mine, this Hungarian director about the same age as me, István Szabó, who did Mephisto, and I’ve visited him when he’s filming him when he’s filming and it’s the same, he’ll go up to Jeremy Irons and just whisper into them very intimately. But then some directors are different, they just talk loud and they bully people into a performance, you know, some actors just learn this themselves, that you get inside each other, that it’s magic, it’s an obsession. It’s not a profession – it’s an obsession.

Film Inquiry thanks Peter Medak for taking the time to talk with us.

The Ghost of Peter Sellers is playing at Melbourne Documentary Film Festival, which is taking place 19th – 29th July 2019. Details about dates and session times can be found here: http://mdff.org.au/

Are you a fan of Peter Medak’s work? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.