Portraits & Polemics: Interview With Critic Jonathan Rosenbaum

Midwesterner, movie lover, cinnamon enthusiast.

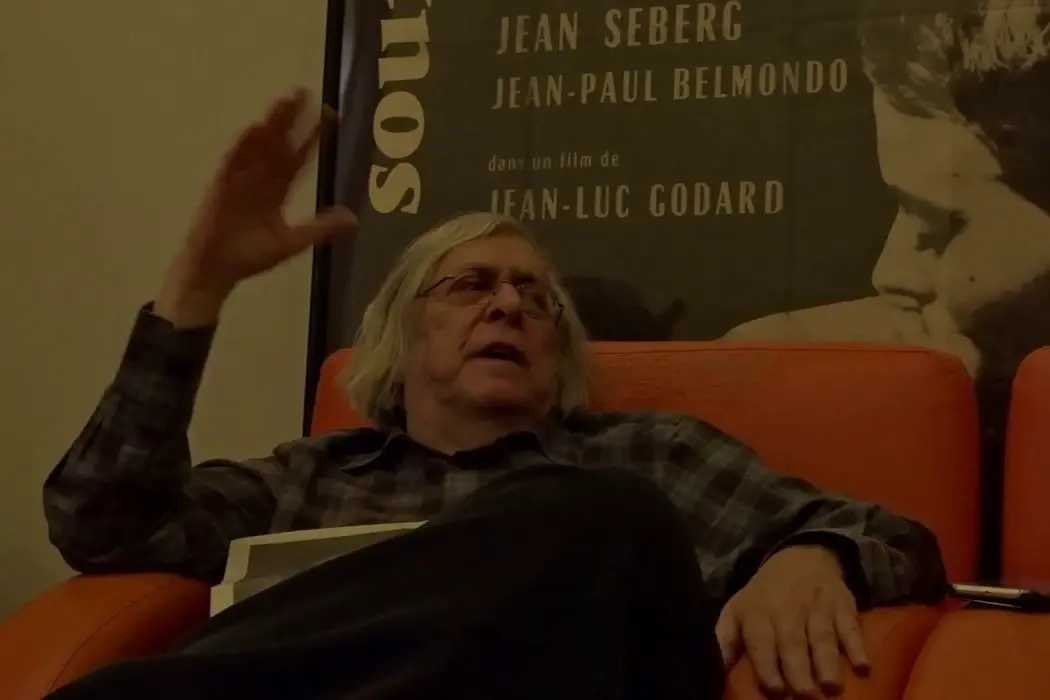

Jonathan Rosenbaum is probably most known for the work he did during his 20-year run (1987-2008) as the Chicago Reader’s principal film reviewer, if not for being the most exhaustive chronicler of Orson Welles and critic of Welles-related writing. Today, he describes himself as a freelance journalist and continues to write regular columns, including his essential quarterly home video column for Cinema-Scope, reviews in Cineaste and other commissioned pieces like the ones found throughout Portraits and Polemics.

His decades of criticism continue to be relevant, enriching and influential to a generation of film fans that were just children during his heyday. This is no doubt bolstered by Rosenbaum’s tireless archiving of his own work on his personal website, which he updates on a daily basis, and subsequently posts to his Twitter and Facebook pages.

Where some of his contemporaries (and many of today’s film critics) fall prey to pure prose or are motivated to simply build structure around their central argument or take, Rosenbaum’s search for meaning always feels intensely honest and prudent, bolstered by an ability to contextualize most films and filmmakers within a vast bank of literary, film and film criticism knowledge.

His new book, Cinematic Encounters: Portraits and Polemics, is a sister volume to the November-released Cinematic Encounters: Interviews and Dialogues. Where that book compiled interviews the critic had composed over previous decades, this one assembles essays and reviews Rosenbaum has written for home video booklet commissions, repertory programs, and sundry publications.

Portraits and Polemics is sectioned into 24 chapters, by director, and continuing from the first volume, seeks to “position that film critics are ideally moderators and facilitators in a public discourse that exists independently of them rather than solitary voices or ‘experts’ who should have the first or last word.” Rosenbaum obviously situates this book in dialogue with the previous one, but he also frames much of it as a set of arguments, either with himself, the filmmakers or his contemporary film critics.

It packages together many of his pet international auteurs, such as Chantal Akerman, Alain Resnais, Bela Tarr and Jacques Rivette, along with some favorite American filmmakers, like Welles and Jim Jarmusch. But then there are some filmmakers that I, personally, have not read Rosenbaum on before, mostly due to their exclusion from previous collections (that I’ve read), and was delighted to discover included here, like James L. Brooks, Jia Zhangke and Richard Linklater.

Rosenbaum recently let me bend his ear for a few questions over email to talk about his book and current life in film.

Shawn Glinis for Film Inquiry: This book is another that demonstrates the importance you’ve placed during your career on bringing exposure to non-American cinema that went beyond what seems to be the cursory attention that many of your contemporaries paid. Do you still see this as a responsibility of yours, or do you see your place in film criticism as having entirely changed since leaving an alt-weekly newspaper, writing for more boutique outlets?

Jonathan Rosenbaum: My interests certainly remain the same, although my methods and opportunities for pursuing those interests have changed somewhat. Although I still attend some press screenings — I saw the disappointing documentary about Mike Wallace last night — I also depend more on the advice of friends and acquaintances than I used to. At the moment, I’ve just started to watch Rat Film via streaming, prompted by a tweet from Kevin B. Lee that mentioned it was his favorite documentary of last year.

I also depend far more on social media — mostly Facebook and my own website — to express myself. This provides me with fewer readers but a far more focused and interactive group. I’ve also been teaching more over the past several years — in Tehran, Split, Zagreb, Madrid and Sarajevo (among other overseas venues) as well as in the U.S. (mostly Chicago and Richmond) — which I mostly find very gratifying, for similar reasons.

I’m not sure if you happened to see that Rat Film was quite the topic just yesterday after Donald. Trump Jr. referred to it in a tweet to attack Elijah Cummings’ urban planning. One of the things I enjoyed in this volume was hearing how you’ve revised earlier thoughts on particular films after revisiting them years later, which is also a common thread in your Cinema-Scope column on home video.

I’m at the stage of my life, in my mid-30s, where I find it exciting to revisit works that I had tossed off at a younger, more naive age — things that you’ve made me want to revisit here, like Me and Orson Welles or Spanglish — to see how they resonate with my current understanding and outlook on life, relationships and art. But most of my viewing is dedicated to exploring parts of film history I’ve not experienced. What is your viewing diet like now, as someone who has seen so much, and what is it dictated by, aside from those recommendations from friends? Is it mostly stuff you haven’t seen or are you always trying to revisit films, as your own life changes?

Jonathan Rosenbaum: I’m always trying to do both. Yesterday, thanks to Nicole Brenez, a friend in Paris, an Iranian filmmaker named Saeed Nouri sent me a link to a terrific new film of his, a documentary called Women According to Men that assembles clips from the earliest Iranian talkies up to the Revolution, cataloging the way women have been depicted in Iranian films. The results are both devastating and illuminating, sometimes in unexpected ways (such as the various kinds of artistry found in some of the excerpts). It taught me a lot about both the past and the present, as well as about my own assumptions (both well-founded and misguided) about Iranian cinema.

As for Rat Film, Kevin’s recommendation from his perch in Germany was of course prompted by Trump’s recent racist abuse of both Elijah Cummings and Baltimore, and this brilliant and original essay film couldn’t have been more timely and relevant. Which prompts me to add that what rules my viewing diet has a lot to do with the pleasure and enlightenment that I can derive from interrogating myself (in terms of re-seeing films that I haven’t experienced for many years) and/or thinking about the present in historical terms (which is where and how both Rat Film and Women According to Men become very exciting in their relevance). In other words, you might say that I’m interested in movies that can improve the quality of my life, not in movies designed as escapes for retreats from that life.

Speaking of Iranian cinema, you recorded a commentary for one of Abbas Kiarostami’s films for the upcoming Criterion release of The Koker Trilogy, alongside your coauthor (of Abbas Kiarostami) Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa. Can you talk about the experience of working on that, whether you were consulted for the set elsewhere, and whether, when you are asked to contribute for a subject you’ve previously written on in detail, do you revisit your own work beforehand, and if so, what is the relationship you have with writing you’ve done in the past?

Jonathan Rosenbaum: When Mehrnaz and I were in touch with our producer Issa Clubb at Criterion about our audio commentary, we urged him to include Kiarostami’s early short Orderly or Disorderly in the set — for me the most interesting and profound of Kiarostami’s shorts, although it’s one that has remained unavailable, apparently because Kiarostami himself didn’t like it. I still don’t know whether or not Issa followed our suggestion. (On the other hand, he did follow my suggestion about including Orson Welles’ radio version of Booth Tarkington’s Seventeen on his release of The Magnificent Ambersons; my audio commentary with Jim Naremore on that film was recorded either the day before or the day after my session with Mehrnaz — I forget which.)

Later on, I contacted Issa about a lengthy video interview about Kiarostami that Filmstruck did with me in Los Angeles that was never completed or released, with the idea that maybe Criterion could buy this material for use in a future Kiarostami release, and he eventually wrote me back that he might do this, but decided against using it on the Koker box set.

I can’t remember this with any precision (our audio commentary for And Life Goes On was recorded about eight months ago), but I’m pretty sure I must have reread my earlier writing about the film as part of my preparation.

You include a chapter in this new volume on Jarmusch, another filmmaker you’ve written a book on. You call Only Lovers Left Alive his most elitist and Paterson his most populist. I wondered if you had gotten a chance to see his latest, The Dead Don’t Die, which has been referred to as his first “late” film, and whether you had thoughts on it and what it means for Jarmusch’s filmography?

Jonathan Rosenbaum: I consider it one of his minor efforts. I like the tenderness he shows towards his teenage characters, and the actors are generally fun to watch, but I didn’t find a lot of substance there, and the reverential treatment accorded to Tilda Swinton — even though I’m a big fan of hers — struck me as embarrassing. As a step towards acquiring a more mainstream audience, I would rank it below Broken Flowers.

Two of my favorite chapters in the book were the ones on Akerman and Resnais. In both, you are attempting to more fully color our understanding of the filmmaker’s entire body of work, not just the fictional work (in Akerman’s case) or the full-length work (in Resnais’ case) believed to be their most important. What do you attribute these general conceptions to — the critics with the loudest voice, distribution, lack of pedagogical rigor, something else?

Jonathan Rosenbaum: I attribute all these conceptions and habits to money and the marketplace and their diverse manifestations, including reflexes and habits. Which sometimes just boils down to trying to keep things simple (i.e., simplistic), based on the sometimes faulty premise that audiences prefer it that way.

Film Inquiry thanks Jonathan Rosenbaum for taking the time to talk with us.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.