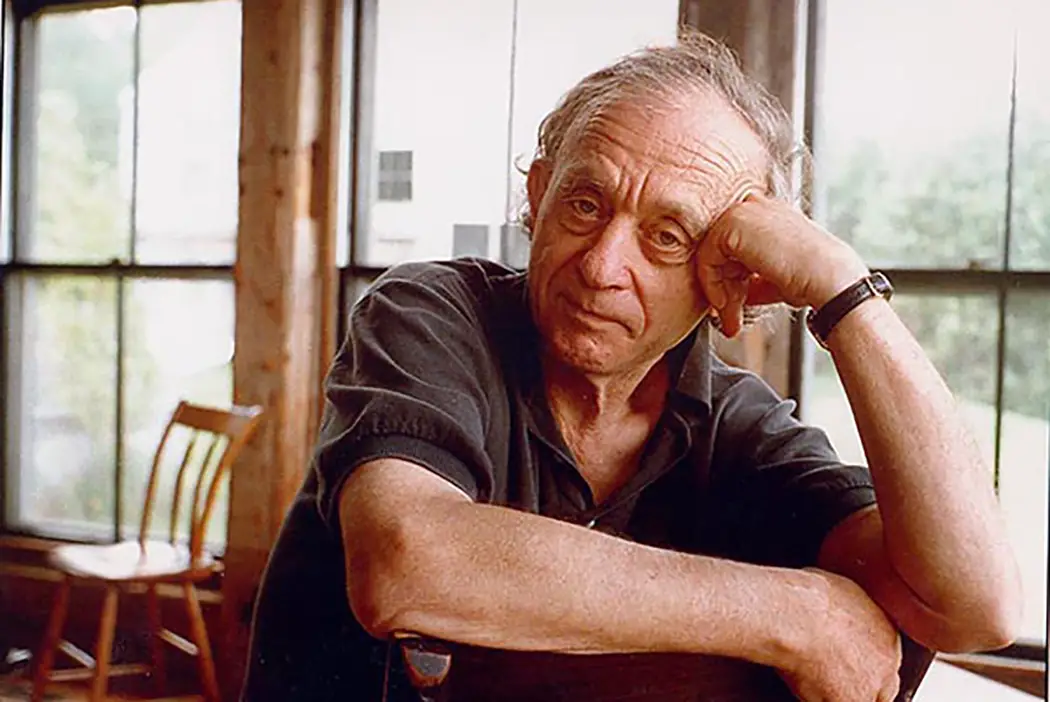

“The Human Experience Is Complicated And Difficult.” Interview With Frederick Wiseman, Legendary Director Of MONROVIA, INDIANA

Arlin is an all-around film person in Oakland, CA. He…

Few have had as much of an influence on their field as Frederick Wiseman has had on documentaries. Starting his career in 1967, Wiseman has produced 42 films, all featuring the relentless persistence of his unique vision. Though he shares with his contemporaries Pennebaker and the Maysles an eschewing of documentary tropes such as voice-over and interviews, he differs largely in presentation. His films employ a distinctive and more freeform assemblage of scenes and moments rather than a traditional linear report, inviting the viewer to participate in constructing the narrative. In the work of Wiseman levity is found in the macabre, surreality in the bureaucratic, and profundity in the mundane.

His most recent film Monrovia, Indiana looks at the life of the eponymous midwestern town and its residents. Mr. Wiseman was kind enough to talk with me through phlegm and congestion about his latest documentary.

Frederick Wiseman: I have a bad cold, so if you can’t hear me let me know.

Arlin Golden for Film Inquiry: Oh yeah, you and me both, I’m in San Francisco and we have the Camp fire raging and it’s just hard to breathe even. But thanks for taking the time.

Frederick Wiseman: Sure.

I know you’re on the junket, must be talking about this film a lot.

Frederick Wiseman: Yeah, it’s in my interest to talk about it.

Oh good! All right, well it’s in my interest too, so glad that works out. I read that you made Monrovia because you hadn’t really made a film in the Midwest yet.

Frederick Wiseman: Right.

Is there kind of a completist element to that? Why’d you even want to make a film in the Midwest in the first place?

Frederick Wiseman: Well I’ve made films in 17 states. And I like the idea, just for my own sense of regional distribution, to work in different parts of the country. And I’m interested in small towns, having previously made a movie about Belfast, Maine, and one about Aspen, and also I think my movie about the Canal Zone is a movie about a small town.

Right. Do you feel that the small town, I mean they’re obviously all different, but do you feel Monrovia specifically is a synecdoche for anything? Or is it sort of a subject unto itself?

Frederick Wiseman: I mean somebody told me, I don’t know if this is accurate figure, there’re 23 small towns in America still. And certainly in the 19th century, and early part of the 20th century, small towns were thought to be the kind of backbone of American life. So I mean, I think that’s part of my interest. Another part was just… for instance I’ve picked relatively large areas or areas where there’re a lot of people, like Jackson Heights, to make a movie. And other places I picked were relatively few people. I mean the smallest group I ever worked with was the movie I did about the monastery where they’re only 25 monks.

Yeah.

Frederick Wiseman: In Monrovia, the population is only around 1,200.

Right. And which I mean, that’s less than maybe High School even.

Frederick Wiseman: Well, High School…at Northeast Philadelphia there were 4,000 students.

Right.

Frederick Wiseman: And on the other hand at Central Park East, there were 250.

I gotcha.

Frederick Wiseman: High School II.

And when you’re shooting films, I mean, what’s the difference in your approach in approaching a whole town as opposed to like a building or an institution?

Frederick Wiseman: Well, in Monrovia I tried to pick places where people met. And where people worked. So they met in restaurants, they met in churches, and they worked in garages, or on their farms, or in beauty parlors, veterinarians, et cetera.

Yeah, it seemed like the settings in Monrovia were largely based in commercial areas, a lot of commerce. You know, there’s different restaurants, there’s a tractor auction…

Frederick Wiseman: The public aspects of life, of daily life.

Yeah. Did you have any sense for sort of leisure activity in the town, would you say?

Frederick Wiseman: Well, you know, there wasn’t much. There were no movie theaters. People went to church. There was a little league, but I didn’t shoot the little league. I deliberately didn’t go into people’s homes because I didn’t want anyone’s home to be thought to be representative.

That’s interesting because it’s different than in Belfast, where we visited a few people in their homes. Why was that?

Frederick Wiseman: Right. I’m not suggesting it was a rational choice, it was just a choice.

I gotcha. You’ve made so many films for so long at this point. When you’re shooting, or editing, or at any stage of the process, how conscious are you of your entire body of work? I mean, do you intend films to be in dialogue with each other?

Frederick Wiseman: Well, you know, similar themes. I like to think I’m aware of the relationship between a scene in one movie and a scene in another.

Yeah. And is that awareness coming while you’re shooting?

Frederick Wiseman: Yeah. There’s the beginning of the awareness while I’m shooting, but the more specific consciousness during the editing. I mean, during the shooting I’m aware of when a scene is good, for example, when I got whatever subjective definition is involved in “good”. But it’s only when I study the material in the calm of the editing room much later that I begin to develop a sense of the real… what I think to be the real significance of a sequence. Because in the editing I have to think that I understand what’s going on in each sequence in order to make the decision – first, whether I want to use it, and second, how I’m going to cut it down to a usable form, and third, where to place it.

Right. But, so if there’s a scene…there were a couple in Monrovia that kind of stood out to me as parallel with Belfast. There was the great Lion’s Club bench scene, which made me think of a moment in Belfast where someone’s asking to remove benches because there are too many kids hanging around there. And then the dichotomy between the high school instruction scene in Monrovia talking mostly about local sports heroes, versus in Belfast talking about Moby Dick.

Frederick Wiseman: Mmhmm.

And the symbology of it. I mean, are you intending to draw comparisons?

Frederick Wiseman: Well, Moby Dick… I mean, no. Naturally I thought of the Belfast scene with Moby Dick, but I’m not using that to draw a comparison between the education in Belfast and the education in Monrovia. Because, you know, there might’ve been another English class where they talked about Moby Dick in Monrovia. In the couple that I went to they didn’t. So I’m not deliberately underlining the difference in educational content between the two places. Because if I were doing high school film about a high school in Monrovia, rather than the village, that might be a valid comparison, but since I only went to a few classes in the high school in Monrovia, I’m not suggesting that that’s the difference between the high school in Monrovia and the high school and in Belfast.

Right, ok, that makes sense. There’re so many different American experiences, and Monrovia is a much smaller community than maybe most or many Americans have experiences with. When you’re filming something like a grocery store, for instance, something that’s ubiquitous to American life, but within the setting of this small town, how much are you weighing relatability versus idiosyncrasy? Like do you want your audience to feel like, “Oh this place has been so different from where I live”? Or do you want it to feel like “this is a unique element of this community”?

Frederick Wiseman: I’m in no position to compare and contrast the nature of grocery stores.

(laughs)

Frederick Wiseman: What I’m doing is in the sequence in Monrovia, in the only grocery store in town, is showing you the nature of the kind of foods that are sold there.

Yeah. And I know you don’t think about your audience when you’re making a film, but to some extent you’re aware that your films screen at festivals there, they have theatrical runs in art houses in big cities. Like how are you managing that?

Frederick Wiseman: I don’t mean to sound pretentious when I say “I don’t think about the audience”, I just don’t know how to think about the audience. Because I mean, for example, I don’t know, first time I’ve talked to you that I’m aware of. I don’t know anything about your educational background, or your interests, or what movies you like, or what movies you don’t like. I don’t know how old you are. I don’t know the nature of your worldly experience, for lack of a better phrase. I don’t know if you’re married or not, how many children you have. I don’t know what college you went to. I don’t know if you read novels, et cetera. So I have a hard enough time making in my own mind about what it is that I’m seeing and hearing. And I think it would be totally pretentious to try and anticipate what anybody else would think.

I think what people do when they try to do that, is basically they seek some fantasy of the lowest common denominator. Which may well not be true and probably isn’t true. But it’s their idea of the lowest common denominator in order to potentially reach the largest audience. I don’t know how to do that. So I just try to make a movie that meets my own standards. I’m very conscious of trying to make the events in the movie comprehensible. I don’t know how to make them comprehensible to you. The only reasonable effort I can make is making them comprehensible to me.

Yeah. Is that comprehension mostly done in the editing room?

Frederick Wiseman: It’s done in the editing room, yeah. Well, it’s done in the shooting too, to some extent. I mean, there’s no scene in the movie, except maybe for some transition shots, that isn’t substantially reduced from its original length.

Of course.

Frederick Wiseman: So in making the choices about how to compress that sequence, I have to be conscious of making sure that what’s left is understandable.

Right, right. You’re shooting all day for weeks. How do you spend your time there when you’re not shooting?

Frederick Wiseman: Sleeping!

(laughs) Are you interacting with the people?

Frederick Wiseman: (laughs) Well yeah, I’m interacting with the people; during the day when you’re shooting, most of the time you’re not shooting! For instance, I probably was in Monrovia 10-12 hours every day. But the most you might shoot in the course of a day is three hours. The other nine hours I’m not always interacting with the people in Monrovia but a good part of that time I am. Because, you know, people are interested, they want to know where you come from, they want to know how the camera works, they want to know how the tape recorder works, they want to know how the movie’s going to be used, they want to have a cup of coffee and ask you questions about yourself.

So I’m deliberately no way distant from the people who might be in the film that I meet. Because, I mean, it’s also part of the way the movie gets made, because the people at the place, in this case the residents in Monrovia, know a great deal more about it than I do. I mean I’d been in Monrovia for two hours before I started shooting. Six weeks previously, or two months previously, I forgot. And so I’m very dependent on their making suggestions; that’s true of any film.

I’m in a welfare center and somebody says to me “Friday morning is usually very busy” or somebody says, “well, every Friday at 2:30 there’s a staff meeting” So I make a little note in a notebook I carry around with me saying “Friday, 2:30 staff meeting, room such and such.” I’m dependent on informants in the most elevated sense of the term “informant”. People who live there, or work in a place, know much more about it than I do. So I try to learn from them about where to go. For example, I got to the auction, a machinery auction, in Monrovia because that group of men that met every morning to have a cup of coffee or breakfast, it was a floating group of 20 or 30 men who showed up. Not everyone showed up every morning, but many of them showed up every morning, sometime between 6:30 and 10:30. They started talking about an auction and I said, “what’s the auction?” And the man that owned the auction company said to me, “well, I go around the country collecting farm machinery; every two months I have an auction. People come from all over the country, and sometimes from all over the world, to buy equipment.” So I said, you know, “when’s the next auction? Can I come?” And he told me.

Yeah. Okay, that’s interesting. I’ve read that you say that you consider your films to be more novelistic than journalistic. Do you consider them also the anthropological to any degree?

Frederick Wiseman: Well, you know, I never studied anthropology or anthropological filmmaking, so my answer may be a naive one. But I would say…I suppose there’s a relationship, but I’m more interested in using the material to construct a dramatic narrative. And that’s completely artificial and subjective.

Of course. That’s interesting, I think a lot of people consider many of your films to be non-narrative. I mean, a lot of them have narrative threads, like some of the community organizing in Jackson Heights maybe, or the plight of the one guy in Titicut Follies who’s just trying to get out and make them see that he’s sane. But so you’re thinking through the assemblage of Monrovia…what is the narrative there?

Frederick Wiseman: Well, at the risk of your thinking that I’m giving an evasive answer, the narrative is what you see in the film. Nothing in the final film is there by chance.

Right, of course. Are you a vegetarian?

Frederick Wiseman: No.

No, okay. I just feel like there’re so many scenes in your films of butchery or…

Frederick Wiseman: I don’t eat meat, but that’s primarily for health reasons. But I eat fish, and occasionally have meat. I mean it’s good to stay healthy under any circumstance, but I have to stay healthy in order to make the films. In part it’s a sport.

You still riding your bike?

Frederick Wiseman: Yeah, I am.

Awesome, that’s great. I mean if it’s a sport, you’ve been making films for decades, what’s compelling you at this point?

Frederick Wiseman: Well, I like doing it! I feel very lucky in the sense that I made my first movie on my own when I was 36 and I really enjoyed it and I feel very lucky to have uncovered a passion for something which I’ve pursued passionately ever since, and it’s now a long time.

And yeah, through the pursuit of passion, I mean, you have influenced so many people. Your name is an adjective to some degree; people refer to films as “Wiseman-esque” or owing to Wiseman. Have you had a chance to sort of keep up with the new crop that you helped to inspire?

Frederick Wiseman: No, I hardly ever go to the movies. You know I spend most of my time in the editing room.

Right.

Frederick Wiseman: After 10, 11 hours in the editing room…I’m looking at the small screen… I like to see movies, mine or anybody else’s on the big screen. I don’t go to the movies very often. I go to the theater a lot, and I like to see dance movies, I go to the ballet a lot. That’s not quite as accessible except in big cities like San Francisco, New York, Paris, London, Rome, etc.

Since Titicut Follies, your first film… I wouldn’t say your films are confrontational, but they don’t shy away from anything, and I think Monrovia is no exception. Where does that come from? I mean by this point I would say you’ve earned it but, but a lot of your films feature really difficult scenes for different reasons.

Frederick Wiseman: Yeah. I think there’re difficult scenes because reality is difficult sometimes. And I think one of the ideas that unites all my films is that they’re explorations of common experience, of daily experience. And sometimes, obviously in a wide variety of settings, I mean the human experience is complicated and difficult. I don’t think I, at least I hope I don’t, overdo it, but I certainly show it when I come across it. I think a lot of my films are funny too!

Oh yeah! Your films are hilarious, I’ve always thought so. But I mean, that’s what you’re saying; that’s human experience, there’s horror and there’s hilarity. Do you think you could show your films to people in Europe or Asia or anywhere around the world and kind of say, “this is the U.S. This is kind of who we are”?

Frederick Wiseman: Well, you know, I don’t know that I would reach for the statement “this is who we are.” But my films are shown a lot all over Western Europe. And almost all of them have been shown in Japan. And many of my films are very popular in China, and I sold my first one to China this year.

Oh wow. It was Monrovia?

Frederick Wiseman: No, it was Ex Libris. But my films were popular in China because they were pirated. But Chinese television bought Ex Libris.

Okay, interesting. Yeah, I remember, I mean, for the longest time I had been wanting to watch your films. And maybe 10 years ago or so I happened upon them at a video store, when those were still around, and it took that to sort of break into them. But now they’re all on Kanopy.

Frederick Wiseman: Right! Right.

Yeah. Which is a great service. Why now to make that leap?

Frederick Wiseman: They weren’t available on Video On Demand and Kanopy made me a reasonable offer, so I figured I was probably late on making them available on VOD, but I’m glad that I did.

Yeah, I’m glad you did too, thanks for taking their offer!

Frederick Wiseman: Thank you for doing the interview.

Yeah of course!

Frederick Wiseman: Going to go nurse my cold.

Film Inquiry thanks Frederick Wiseman for taking the time to speak with us.

Monrovia, Indiana is in theaters now. Check here for a full list of showings.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Arlin is an all-around film person in Oakland, CA. He received his BA in Film Studies in 2010, is a documentary distributor and filmmaker, and runs Drunken Film Fest Oakland. He rarely dreams, but the most frequent ones are the ones where it's finals and he hasn't been to class all semester. He hopes one day that the world recognizes the many values of the siesta system.