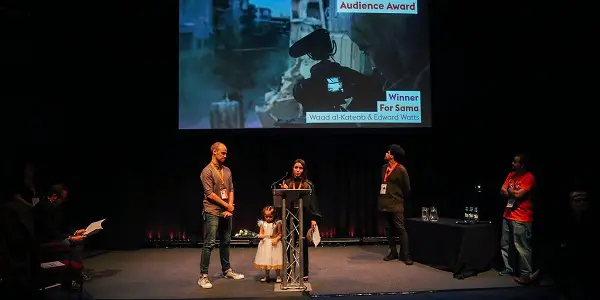

No film received a more rapturous response than the extraordinary, harrowing, and extraordinarily harrowing Syria doc For Sama at this year’s Sheffield Doc/Fest. It feels like the first work about Syria in some time to enter the public consciousness deeply and prompt us to pay attention, based on the immediate impact it’s had on spectators, further demonstrated by its victory of the coveted Audience Award at the festival.

It’s self-shot from the perspective of Waad Al-Kateab , who was a student at the University of Aleppo when she began recording footage of her daily life in the city, and soon gave birth to a daughter, Sama, for whom the completed film is a visual letter, made in collaboration with skilled documentary filmmaker Edward Watts . I wrote more about For Sama in my festival coverage here .

I was fortunate enough to sit down with Waad al-Kateab and Edward Watts and speak to them about the reactions it’s received, making a film out of a mountain of archive footage, and the responsibilities of telling the Syrian story.

This interview was conducted on Tuesday, June 11, 2019 thanks to Hayley Barlow, Director of Communications at Channel 4 News, and Louise Plank, Director at Plank PR. For Sama is produced by Channel 4 News and ITN Productions for Channel 4 and Frontline PBS.

Musanna Ahmed for Film Inquiry: I’ll start with the first thing that many people will ask after seeing your film. Because it’s so indicting of the international community’s response, including from our country, what can we do to make a difference?

Edward Watts: We were discussing this a lot today.

Waad al-Kateab: What happened when we were besieged in Aleppo was a lot of people around the world were protesting against what was happening, saying “save Aleppo” and “save the people who are there.” But just two kilometers away, the Syrian regime and the Russians were committing massacres and no one really knew what happened because they were killing everyone .

No one outside knows what’s really going on there but we do believe that, because of the people on the outside making this noise, that’s brought a lot of attention, especially to Russia who really care about their prestige in the world. We got out safely because of the attention brought on by these protests. I call on everyone to be a part of any protest, to stand and make noise about what’s going on in Idlib, because that’s the land where people can live in Syria without being under Assad’s control.

Edward Watts: Yeah, and I think that the only thing to add to that is – were you there yesterday (Monday 10 June)?

No I was there for the first screening on Saturday (8 June).

Edward Watts: Right, what I was saying after yesterday’s screening is that it’s so easy for people to feel helpless. And that story that Waad just told… in fact the whole film and these guys’ story is about what individuals, who don’t give up, who do believe that they have the power to affect change and make an impact, can do. And it’s just that thing of what Waad is saying, just sharing the news, telling the world, telling your family about what’s happening in Idlib, telling them that Syria is not done and people are still dying today as they were three years ago.

Every single individual voice is adding to all of the voices. And we were talking to someone today who also said that Russia – as much as it appears as they don’t – they do care about their reputation. And it can make a difference. If they really feel that their reputation is being affected and people are aware of that, they’ll have to change their behavior.

As an extension of that point, because this film is also very clear of Assad and Russia’s wrongdoing, is it possible that the film will reach them? Is there a campaign to get it seen by them?

Edward Watts: We’re talking about trying to get screenings in Russia at the moment. We want to go to the (United Nations’) Security Council.

Waad al-Kateab: This issue is a political one and we’re all political. It’s also a humanity issue and you can’t separate the two from each other. The decision makers will influence if it gets seen or not. The Syrian regime doesn’t care about what’s going on because for them they can feel they can do whatever they want. That’s their attitude – to lie.

At least the Russian government, on the other hand, they’ve killed and gone on to say that they haven’t been killing anyone. So this film is more for the Russian public who could help change that government… I don’t know if this would be something silly to say but if they helped change the government it could be useful not just for Syria but for the whole world.

Edward Watts: It was a Russian woman who came up to us yesterday and said, “I want my people to see this and know what their government is doing in our name.” And I think we’ve seen, in the Russian people, they’ve shown amazing courage in the face of an incredibly authoritarian regime to fight for their values, our shared values.

Waad al-Kateab: You feel that these people are like the Syrian people who aren’t pro-Assad but living in Assad-controlled places. And their regime similarly doesn’t really allow people to see something from a perspective outside, so it’s going to be useful for them to see the other side of the story, of what this conflict is really about. It could maybe create a movement

Yeah I suppose it’s still in the early days to determine that but I imagine through the very positive screenings you’ve had at Cannes and Sheffield, you must be already feeling like there’s an impact being made.

Edward Watts: Definitely!

Waad al-Kateab: Yes we do.

Edward Watts: Someone today said to us that there are so many works on Syrian issues but this film is the first thing for quite a while that’s cut through in the British press at least. It’s got people re-engaging with Syria. It’s such a powerful story what these guys lived through and it’s having this effect that every Q&A, everyone’s like “What can we do?” and we’re coming up with answers on that front.

I like how you mentioned that this is the first text about Syria in a while to cut through to the British press. I think it’s especially because Waad’s footage is just so matter-of-fact, showing exactly what it’s like there. How important was it for you to maintain the rawness? Were there things you had to take out because it was just too much for people to see?

Edward Watts: SO much.

Waad al-Kateab: We put just a little bit of what’s happening. What we’ve shown in this film is 10 percent of what I have, and what I have is literally 10 percent of what’s really happening. This is just one camera in one place – you can’t imagine everywhere else. So we’ve certainly had a lot of conversations about this, and sometimes he felt maybe this footage is right for the film and I said not at all. So, it became more about how we could choose the right things in the right place, and not make it too much.

Edward Watts: On her point, we had a lot of discussion and conversation about what to put in and we agreed from the start that we had a responsibility to show some of the harshness. We shouldn’t protect our audience completely in the way that Western audiences are so protected now from seeing the reality. Our starting point was in all this horror that Waad saw and lived through and captured. We’ve had to retain enough of it so that people understand what the war against civilians looks like. It’s about the fact that children really are lying dead.

Waad al-Kateab: And, you know, not showing this is not going to give us a solution. You can’t close your eyes to what’s happening. You should open your eyes and see exactly what the Syrian people are seeing with their own eyes. It’s not a Hollywood film. It’s not something we create. It’s really happening. The worst thing is that it’s still happening even now. It’s not like the end of the film means it’s all finished. So it’s a big responsibility for us to get people engaged with reality and share that responsibility between our audiences and the pictures, to tell them exactly what you are seeing now is not finished. It’s happening today and tomorrow and the day after until I don’t know when.

Edward Watts: And people want this stuff, you know? That’s the thing – it’s more respectful to the audience to show them the truth and I think the reaction to the film has shown that people are hungry to know the truth about what’s going on. They’re frustrated that they can’t actually get to grips with the reality. So you’re doing a service to your audience by showing them the truth.

Waad, how difficult has it been presenting this film and seeing everything again, basically having to relive those difficult times?

Waad al-Kateab: When I first left Syria, I was trying to ignore what I had just been through and just focused on my family, Hamza and the kids. But I soon felt how important it was to process it through the film and I wanted to do that as soon as possible. It took a long time, two years, because I really wanted to be satisfied with what I had made. At the same time, I felt that the time I would think about it more is if I took a break from it all. I didn’t have that time to rest or think or at least feel that I’m away from the situation.

Even now, I’ve finished making the film in one way but in another way I don’t think it’s finished because I now have this responsibility to go and show it to people and speak to them about it. Any conversation I have with people about the film, no matter what kind of conversation it is, I think it’s really important work because I want them to feel and connect with each other. I don’t want to be resting yet, especially because I’m very lucky to be out of Syria to deliver this message, to share my experience and remind them that it’s still happening. My kids can have a good time now in this new life, which has been a great welcome, but this mission with this film is just as important.

A technical question: I understand that you shot a lot of footage, how difficult was it to construct down to 95 minutes?

Edward Watts: : Well, that’s why it took two years! [laughs] It was very difficult. One of the things you could say is that in Waad’s footage there are loads of different films. With an incredible archive like this, there’s a film about the city, a film about the war, a film about their personal lives, a film about the hospital and so on.

That’s why working together and having endless conversations with our amazing editors was key. Our whole team was great and we could have very honest conversations with each other to get the essence of it all into 95 minutes. It is an incredibly tricky process. [turns to Waad] That look she’s giving me now is that look she gave me when I’d say “what about this?” and “how about this?” [laughs]

I can totally see about the multiple stories within Waad’s footage because I’ve also heard a lot of people say that they like the film also because it’s also a very strong love story at the center between Waad and Hamza as well as a diary for Sama. I saw another film at this festival called Midnight Traveller, about a family in Afghanistan. The father is a filmmaker who’s being hunted by the Taliban, so he and his family make the journey to go to Germany. Everything is shot on three mobile phones. There’s one point when their daughter goes missing from the house and the father has to run outside to look for his daughter and he gives this narration about hating cinema sometimes because his addiction to shooting interferes at times when he shouldn’t be using a camera. Waad, I’m wondering if you had any moments like this during filming where you wanted to put the camera down, dealing with that conflict of “I need to capture this” but also “I can’t or don’t want to.”

Waad al-Kateab: It wasn’t the same situation for me because I wasn’t shooting because I loved to film or because I wanted to make a documentary. It wasn’t my plan to make a film at all, I was shooting because to me it felt the most important thing I could do for the memories of the people around me and myself as people who could be killed in the next month – everything in this life would be gone if it wasn’t recorded history.

Sometimes you do feel like you can’t handle recording something, but at the same you know how important it is not just for yourself but for the memory of everyone and everything that exists in a place. The camera is like a weapon, sort of like a gun, in that it’s the only thing that will protect you during times of survival, even if you know that you might die whilst using it. If we weren’t recording and we had been killed, no one would have a sense of what was really happening on the ground from the people who lived in Aleppo.

Right. So when did you have this moment of, “I think this should be made into a documentary.”

Waad al-Kateab: I had no idea until I left. After I had left, I wanted to do something very, very urgent about the siege in particular. Russia and the U.N. and all these people were very proud of getting us out of there safe but, for us, displacement was the last crime against us. They were proud that they got us out but it shouldn’t have to be like this – there shouldn’t be bombings or massacres on our people. Help people live safely in their homes rather than displace them. I wanted to focus on that idea, I didn’t want Russia to be credited with saving the people of Aleppo because displacement was just another one of their crimes.

I wanted to do something in two or three months, nothing very big, but I had been working with Channel 4 News when I was inside, sending them footage of Aleppo, and they were looking to do something bigger with me than my initial project. I had a great relationship with this corporation and our executive producers, Nevine (Mabro) from Channel 4 News and Siobhan (Sinnerton) from Channel 4, were discussing about a longer form of my story and I was open to their ideas and support.

Edward Watts: They brought me in because I had already made a few other docs and I really cared about Syria. I felt that the whole story of how it all began and what the regime had done hadn’t really been told so it was my passion to tell that story.

Edward, as a storyteller who is very passionate about Syria, I’d love to know what other texts to appoint people to engage with regarding the conflict.

Edward Watts: Wow, well, one of the ones I always remember is Return to Homs. The central character of that was killed just a few days ago. That film had this moment of…

Waad al-Kateab: Uprising.

Edward Watts: Yeah. The joy, which you get in Waad’s footage as well. And in a sense what was interesting about that was that it came out very early, like 2014, and it still hasn’t ended. I think Return to Homs and our film stick out to me…

Waad al-Kateab: I disagree about Return to Homs . It was a really good film but I don’t think it did justice to the situation. The film kind of finished with the character as an extremist without showing exactly how that happened. It’s as if they just wanted to make the film more interesting as a film more than show the reality of what it was. The ending was bad.

Edward Watts: Yeah you’re right, it was a flawed ending. It’s just such a complicated situation and I think there have been amazing bits of art and humanity but you know it’s something to do with our politics that’s compromised it. Like Waad says, that film ultimately went for something that was a bit sensationalist. That’s why we genuinely feel our film – we would say this, I suppose [laughs] – but we do feel our film is good because it’s all from Waad and it’s all true.

Waad al-Kateab: And we don’t present ourselves – you can tell me if you disagree – we don’t present ourselves or the people around us as heroes. We are very normal people who you could meet in any place, anywhere. The Syrian situation has plenty of symbols who could be leaders or heroes while many others are just like me.

The character from Return to Homs was killed a week ago in a battle between the regime and the rebels. Because of that film, a lot of people said that he was one of the extremists, one of the terrorists, when he’s one of my heroes and many other Syrians’ heroes. So, you have to be careful about how you present people and what you want them to be.

Edward Watts: I think the terrorism thing as well is another thing that’s been so frustrating. The frustration about this whole conflict is that so much media has only focused on ISIS. And in a way, that is exactly how the regime wanted to present this conflict, that there are these crazy terrorists running around who can claim they’re justified in their struggle. I think that’s been a difficult thing for audiences, they haven’t been able to access the reality because people have been focusing on these distorted, sensationalist media items.

When you were completing this film, did you run into any challenges of people trying to influence you to make Waad’s story that sort of heroic narrative?

Edward Watts: To be honest, the only people who were trying to influence us was each other and that was enough. Everyone else just stood back and let us have all the discussion. And Hamza too, of course.

Waad al-Kateab: I just wanted to present myself as one of the characters under the light, with a brief history of this city. We had this like…

Edward Watts: Tug of war.

Waad al-Kateab: Yeah I was pulling sometimes, he was pushing sometimes. So I cared about not presenting myself as the only person in the city. I wasn’t the only person under the light and wanted to show the reality of daily lives as much as I could.

It sounds like, as well as the international community needing to respond better, there needs to be storytellers who are more responsible and sensitive and how they present the story. Do you feel the same way?

Edward Watts: I do, actually. I do feel – not I would never criticize anyone. There are amazing artists and you don’t criticize your fellow artists, everyone has their own struggles and difficulties and stuff like that. I think what’s exciting is the more and more that we see people like Waad all around the world who are able to tell their own stories, and we get involved in bringing our experience to essentially support people like Waad to tell their own stories.

That is a fantastic, exciting thing because what really came through in this process was this authenticity, this combination of our different perspectives of Syrian and Western meant that we could create something that was totally true to the Syrians but also could bring a Western audience from nought to 100. When you combine storytellers from two perspectives, that’s when you get the real truth and power.

One final question, as both of you have established yourselves as some of the most important filmmakers with For Sama, is there anything else you’re working on that you could tell us about?

Edward Watts: That’s very kind of you. [turns to Waad] We’re some of the most important filmmakers working according to our good friend here, so what else are you working on?

I understand that the press tour takes a long time…

Edward Watts: The campaign is a full time job. [laughs] It really is.

Waad al-Kateab: More than full time. Sometimes you need to be in two places at the same time. One foot here, another foot there.

Edward Watts: Yeah. [laughs] Speaking for myself, I’ve got some ideas. It’s all about trying to use storytelling to help this world of ours, to get in touch with reality, to get in touch with truth, and you know what? To start actually believing in human beings again, which I think is what you get out of Waad’s story. So often, we’re told that human beings are dark and that we can’t do it and we’re all doomed – we need to start believing in ourselves again and believing that we can make things better.

Film Inquiry would like to thank Waad al-Kateab and Edward Watts for speaking with us and Hayley Barlow and Louise Plank for coordinating the interview.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.