This piece contains spoilers for Don’t Worry Darling

Now that the dust has settled in the wake of the infamously controversial press tour for Don’t Worry Darling, Olivia Wilde’s new sci-fi thriller, it’s time to discuss the film itself. Don’t Worry Darling is a contradiction: While it ostensibly presents a feminist critique of the 1950s (and the present moment) for women, on the notoriously troubled press tour for the film’s release, both director Olivia Wilde and her screenwriter Katie Silberman discuss their affection for the “fabulous” lifestyle women in the 1950s lived. This is, in part, the goal–– both women have described the film as examining the question, “who is actually brave enough to question a system that really works for them in a really amazing way?” an idea which in itself deserves thorough examination. However, even taking this premise at face value, in attempting to critique the seductiveness of the housewife lifestyle from the angle of poolside martinis and black tie dinner parties, Olivia Wilde‘s film falls into its own trap. In tandem with the 1950s-inflected millennial “wine mom” memes of the past decade in addition to the rise of “Tradwife” aesthetics for a vocal subset of Gen Z girls, this nostalgic love of a way of life held up by pervasive cultural and political misogyny both undercuts the film’s feminist credentials and signals a fascinating cultural trend for women today.

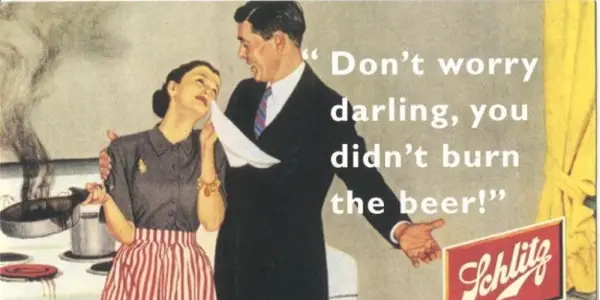

Don’t Worry Darling, based on a spec script by Carey and Shane Van Dyke (children of beloved Marry Poppins star and television staple Dick Van Dyke), was inspired by the virulent sexism of 1950s advertising. The title, per Wilde, was drawn from one such ad that shows a woman with a burning pan behind her, crying in her husband’s arms over an empty dinner table and reads: “Don’t worry darling, you didn’t burn the beer.” The visual style of this ad (familiar to anyone who came across the ironic fridge magnet parodies of them in the 2010s–– more on this later) is carried through the film, a psychological thriller that follows the domestic lives of Alice (Florence Pugh) and her husband Jack (Harry Styles) in the company town of Victory. Ostensibly set up for the men who work at the top secret “Victory Project,” the substance of their husband’s work remains a mystery to the doting wives. Life seems, at first, to be pretty good for the women of Victory. They wear beautiful clothes, drink c*cktails by the pool at all hours, laugh often and fool around more, with husbands more than happy to perform oral sex on dinner tables and ask nothing in return. Only when fellow housewife Margaret (a woefully underused Kiki Layne in the deplorably stereotypical role of the wise, suffering Black woman) starts behaving strangely does Alice stop to look around her and wonder why the women aren’t permitted to leave.

Soon, Alice’s world literally starts to fall apart around her in a series of hallucinogenic flashes. She begins to feel constricted in her life of cooking, cleaning, laundry, and parties early on, but not because she dislikes her existence. Rote visual metaphors illustrate a conventional critique of this era’s sexism: as she cleans a vast wall of windows, it presses in on her until she is pinned, helpless and immobile; she cracks eggs only to find them (like her life) literally hollow. The problem with this structure is that she seems to have no problem with her domestic life itself–– her anguish is a product of her entrapment within what she comes to correctly believe is a Stepford-Wives-style conspiracy concocted by Victory’s men to prevent her and the other wives from leaving town.

Here come the spoilers:

The reality of the situation in Victory, we eventually learn, is that the town is a simulation designed by incels to enslave their wives and girlfriends who lie tied to beds in the present day drugged unconscious, presumably forever, living out the fantasies of their men who feel entitled to total control over their minds and bodies. Alice is not a housewife at all, she is in fact a nurse who works thirty-hour shifts at the hospital to pay the bills for herself and her unemployed, hilariously greasy boyfriend (a particularly hard sell when played by debonair teen-girl heartthrob Harry Styles in a stringy wig) who, upon her arrival home, asks her when she’ll cook dinner.

“Living a Fabulous Life”

And herein lies the contradiction of the film. When discussing her goals for the film with Stephen Colbert, in response to his admission that he would love to live in Victory (“not morally, but in terms of my appetites”) Wilde says that she feels “the same, which is even worse because I’m a woman! I shouldn’t want to live in a 1950s Rat Pack world” but that the film is examining the seductiveness of a model of comfortable, “fabulous” living in the system of the time afforded women. She and Silberman echo this point in a Q&A, saying that they were tonally inspired by the films of Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack (“what a blast they seemed like they were having, how much fun their lives seemed to be”) as opposed to making it “[feel] like a horror movie.” They did this, they say, as a way of investigating how to resist “the spaces you could maybe convince yourself were okay even if they were based in something rotten” because, “Everyone in modern society is existing in that space. We’re aware of how bad the system is, and yet we exist in it and we benefit from it.”

Fundamentally, the critique Wilde and her team are attempting to make isn’t necessarily a wholly incorrect one. The 1950s, though incontestably a repressive time for women, wasn’t always an overtly nightmarish one on the surface, and not every woman felt oppressed. This critique was expressed by Joan Didion in her essay The Women’s Movement in her seminal book The White Album: “That many women are victims of condescension and exploitation and sex-role stereotyping was scarcely news, but neither was it news that other women are not: nobody forces women to buy the package.” That being said, this kind of assessment in Don’t Worry Darling feels woefully empty for myriad reasons: obvious questions of race, class, and sexuality fall by the wayside in this model of simple “we all benefit in the system” commentary in both the past and the present, a fact they gesture to only weakly with Kiki Layne’s one-dimensional character of “the Black woman who knows something is wrong with a calculatedly diverse town modeled off segregationist 1950s suburban America.” Equally fundamentally, leveling this featherlight critique from the vantage point of a Margaret-Atwood-style parable of literal sexual enslavement by incels modeled after Jordan Peterson rings hollow at best, insidious at worst.

What’s more, the fantasy these incels create for themselves is remarkably pleasant for the women they’ve enslaved: the men and women get along well, they give their wives oral sex eagerly, and no one ever hurts their wives or even berates them unless they attempt to escape. Only one scene demonstrates a traditional example of the male gaze, a show-stopping striptease sequence with burlesque star Dita Von Teese, however, the crisp, artful cinematography makes the scene feel more like a trip to the theater than to the peepshow, undercutting any potential indictment of the men’s behavior. Even Frank (Chris Pine), the Jordan Peterson stand-in whose podcast is broadcast as a radio show to the women of Victory daily, has notably little to say about “women’s roles.” Additionally, for a character like Styles‘, whose central line in the modern flashbacks can be succinctly summarized to that old misogynist chestnut, “make me a sandwich,” this seems unrealistic. And for a film inspired by the films of Frank Sinatra, a man who famously divorced Mia Farrow when she wouldn’t drop out of her iconic role in the feminist classic Rosemary’s Baby–– of which this film’s themes and conspiracy narrative are ostensibly also inspired–– this overall lack of overt sexism from the men creating this world is ironic. Even the pat sexism of the types of ads that inspired the title is conspicuously absent.

Conversely, the idea that Alice, a woman who, when she finally remembers her real life, claims to “love” her work as a nurse would feel perfectly content to an existence entirely bereft of intellectual stimulation or purpose outside her romantic relationship harkens back precisely to the early 1950s time period ostensibly being critiqued, around the same time Betty Friedan‘s “problem with no name” in her classic the Feminine Mystique blew the top off of the myth of feminine domestic bliss. Indeed, frustrated missives from Friedan‘s interview subjects parallel large swaths of the film’s plot: “my days are all busy, and dull, too… I get up at eight––I make breakfast, so I do the dishes, have lunch, do some more dishes, and some laundry and cleaning in the afternoon. Then it’s supper dishes… the children have to be sent to bed… that’s all there is to my day. It’s just like any other wife’s day,” yet Alice smiles pleasantly as she straightens sheets and vacuums carpets until a glitch in the incel matrix starts to indicate to her that something else is going on underneath it all.

All of this begs the question: why is this movie like this?

Conclusion:

Olivia Wilde‘s primary goals for the film seem to be fundamentally at odds with each other. The feminist themes inherent in a parable concerning subjugation, control, and manipulation are incompatible with her desire to make, first and foremost, a “hot movie.” As she puts it, “I wanted it to be a hot movie that’s a good time and that if later it leads to some conversations, that’s great… As a female director, it was quite funny for me to be the one saying, ‘I need more bikinis, more tans. I want everybody sexy, sexy, sexy.’” These aims are clear in the sumptuous mise-en-scene and gorgeous sun-drenched, pastel cinematography inspired by Slim Aarons’ photography. They also cause the majority of the more fraught political paradoxes in the film as a text: when on the one hand Wilde explains her incel inspiration for the film’s villain as “basically disenfranchised, mostly white men, who believe they are entitled to sex from women,” and on the other boasts to Variety that “Men don’t come in this film… only women here!” in her discussion of the film passing “The Clit Test” for its oral sex scene, neither the film’s feminist political stance against misogyny nor its emphasis on aesthetics of pleasure for women are able fully come across as fully coherent. The hedonistic vision of this “easy” “fun” lifestyle she’s depicting is simply too seductive for the script she’s attempting to produce, whether or not her central tonal goals align with its broader political message; rather than toe the line to make her more nuanced point about comfort and culpability, unfortunately she and Alice fall down the rabbit hole and do little more than provide visual fodder for the tradwives of TikTok who glorify the aesthetics of “traditional gender roles” and echo the aesthetics of millennial “wine moms” who ironically deployed the selfsame 1950s ads as a way of expressing their unhappiness.

Rather than imply that, deep down, all women want to live the lifestyle of the 1950s, these resurgent aesthetics strongly suggest a deep dissatisfaction for some women with modern existence. But rather than encouraging political action, texts like Don’t Worry Darling encourage passivity in their focus on the “seductiveness” of the material to the detriment of their politics. In Wilde’s words: Though I could kind of judge the lack of autonomy at the time [the 1950s], it also seemed like a really fabulous life… I mean, martinis for breakfast? Like, why not!”

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.