The Individual In Edgar Wright’s Cornetto Trilogy Part III: A Return To Anarchy In THE WORLD’S END

I'm a film journalist and independent filmmaker who fell in…

After examining fascist entities and their victims in both Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz, Pegg and Wright would finally balance out the sense of entrapment and hopelessness with a different kind of order in their final foray in the trilogy with The World’s End (2013). Dive into the murky underbelly of deep regrets, unresolved ambitions and the dangers of youthful fantasies, which are all bubble-wrapped with the threat of losing one’s identity and soul, The World’s End, is, arguably, the ultimate destiny for the collective spirit of Pegg’s characters. It arrives at the point where the ideas and themes from the first two films intersect, while also fulfilling desires that have been gestating from the beginning. With that said, let’s bring the noise!

The King

Gary King (Pegg) is a wild card; a symbol of anarchy, but one that invites chaos and disorder with his immaturity and recklessness (making Shaun look like a success story). He also has taken to identifying himself as “the king”, because he lives on a different plane of reality than others do, and yearns for an older world that had less boundaries and more adventures. Gary idealises a single night from his youth to be the most magical he’s ever had, which was when he and his best mates tried, but failed, to conquer The Golden Mile, a pub crawl consisting of twelve establishments in their hometown of Newton Haven.

For whatever reason, Gary can only be “The King” by association with his school chums, whom he feels enables his jubilant spirit (but really adolescent entitlement), and refers to this collective as the royal “we”. He mythologises his time as a young man, by viewing it through the prism of medieval adventures, where he felt like a literal king, hanging out with his band of “knights” (or even musketeers) as they embark on “quests”, marching into villages by means of the “beast”; a British Ford Granada, beaten and bruised, that Peter sold to Gary, which he treats as his noble steed (serving as another indication that he is desperately holding onto an ideal past).

With the band splitting up, everyone moved on into securing themselves with careers, wives and families, and live an adult life for over two decades. Everyone expect Gary, of course, who found himself battling alcohol, drugs and major states of denial, due to him being a slave to his rebellious youth; shackling himself to the idea of being invincible and taking on the universe, while unable to deal with reality because he doesn’t really know his place.

The Heroes’ Quest

After attempting suicide (unbeknownst to his friends) and having to abide by a strict regiment at a rehabilitation facility, Gary feels that completing the Golden Mile is all he has, as he considered that “quest” to be the beginning of his life. He reunites the old gang, who consist of: Andy Knightley (Nick Frost), Steven Prince (Paddy Considine), Oliver “O-Man” Chamberlain (Martin Freeman), and Peter Page (Eddie Marsan). None of them are particularly interested in revisiting Newton Haven, especially since they do not want to appease Gary King, whom they consider to be childish, immature and pitiful.

To Gary, Newton Haven was his paradise and playground, but to others, it is a black hole full of childhood trauma, despair, false promise, fantasy, old wounds and unresolved issues, all of which thwart people’s growth. However, by moving away from their hometown, the boys haven’t really fixed their problems, they simply repressed them and disguised them with success. They openly fear social hierarchy, while Gary has constantly rebelled against the status quo, not recognising any form of authority, and chooses to indulge in heavy drinking to modify his perception of reality.

A third of the way through the current attempt at The Golden Mile, Gary finds that the conflict between him and Andy (who never forgave him for abandoning him while he was drunk, injured and eventually arrested during the initial Golden Mile) has festered to something more bitter, with Andy tiring of Gary’s shenanigans and urging him to “grow up and join society”.

The Blanks

In the pub’s bathroom, an angry Gary (who also notices an imprint on the wall that he punched during the first Golden Mile) tries making small talk with a young man, whom he considers of his own parish. After the man ignores him, Gary provokes him into fighting but the man is eventually revealed to be a “blank”.

In actuality, they are androids controlled by an alien entity named “The Network”, who have sought to replace human beings with more enhanced, “improved” versions of themselves, in the hopes of getting humanity to join a vast galactic community. Those who refuse to conform will be transformed into one of them instead; becoming empty vessels that will spread their ideologies through “peaceful indoctrination”. The blanks are not unlike the zombies from Shaun of the Dead, serving as a more explicit commentary on blind conformity, while the idea of a totalitarian takeover echoes Hot Fuzz, where a network of beings adopt a “join us or die” mentality.

Both Gary and the blank get assistance from their respective mates and a bathroom brawl ensues, with the musketeers gaining the upper hand. Deciding it is better that they continue with their pub crawl to avoid unwanted suspicion, the gang move from tavern to tavern, having their drinks and keeping their eyes peeled, as they try to figure out what has happened to the town. They are constantly eyeballed by the blanks, who view them as “individuals” and “others”, who openly defy their unity. The musketeers are threatened by domination after bumping into figures from their past, including a trio of sirens they lusted after in their youth, and their old school principal, Mr Shepherd (Pierce Brosnan); all of whom are blanks, trying to manipulate and seduce them into their cause.

Worst of all, is how the blanks taunt people into confronting their past horrors. In Peter’s case, his childhood bully practically ignored him at the start of The Golden Mile, which deeply affected him as it demonstrated that it was all for nothing. Once everything was out in the open however, he came back attempting to reconcile their differences. In a fit of rage, Peter attacked the blank, before being captured and turned into one of them.

Based on information given by Basil (David Bradley), one of the stranger people from their school, the Network can create replacements through DNA samples from blood or saliva. Mistrust arises after it turns out O-Man has been replaced by a blank (after noticing that his pre-surgery birthmark has returned), and everyone becomes suspicious of one another (another call back to John Carpenter’s The Thing). All is resolved once everyone is forced to exchange body scars and specific bits of information and character behaviour that only they would recognise (and that also happen to be things that the Network ignores in their designs for fear of being too primitive for their vision).

End Of The Line

With the chaos reaching a boiling point, and the blanks chase after the musketeers, Gary finally finds himself at The World’s End, the final destination in The Golden Mile, with a fresh pint waiting for him. Knowing how taverns and alcoholic indulgence carry tremendous weight in the trilogy (especially as means of mental distraction for the “subjects”), the final pint is like discovering the holy grail in Gary’s ultimate quest in his heroic endeavour.

Discovering that Gary attempted suicide, Andy tries to persuade him that despite the fact that his own life isn’t perfect (his marriage is in shambles), he continues to fight for it, as human beings do to survive. Despite the cathartic moment, Gary holds onto the belief that he has nothing left, and in a struggle the pint is destroyed. As Gary tries to make a new one, the area turns into a platform that descends to an underground lair where they confront the Network (Bill Nighy).

There, the Network offers Gary the fountain of youth; a chance to going to back to being, what be believes, was the best he ever was, forever. All he would have to do, is give up his individuality and soul, and become part of an expansive machine of perfection.The Network proves to be a far more formidable opponent than any of the previous antagonists in the trilogy. Like Oceania in 1984, the Network has a tight grasp on the past, which gives it complete control over our future. Tapping into our deeply-rooted desires, dreams, fears, fantasies and traumas, it knows precisely how to manipulate us and dangles the juiciest carrots in front of our faces to make us submit to its every will and order.

Just as Orwell demonstrated the “memory hole” concept demonstrated in 1984, social media or high figures of influence can hide, remove or sanitise our flaws to create the ideal or “perfect” image that we’d wish for. Shaun of the Dead began with a simple metaphor of how powerful things like governments and (social) media can dominate our lives and past times, keeping us disconnected from one another and ignorant of serious matters around us, thereby “deleting” our humanity and soul. With Hot Fuzz being a transitory period that illustrates the cycle of ignorance (beginning with people oblivious to dictatorship to becoming those dictators), we are back at the point where the totalitarian regime that shapes our destiny literally ask us to give up our identity and become one of them or live in fear under their leadership.

The numerous phrases and references to Arthurian mythology that Gary spouts throughout the film are not just for show; he firmly believes in the strength of an individual, on how one person can make a difference by standing up to invaders & power-hungry entities in a large hierarchal machine, and create an iconography around them. He simply confuses facing adult realities & responsibilities with conforming to a sheep-like society, which is what Andy was advising him about (in a twist where the Nick Frost character isn’t an advocate for self-destruction).

After literally looking at his younger self, Gary rejects the Network’s offer, and (while heavily intoxicated) literally takes on the supreme beings of the universe, defending humanity’s flawed and primitive nature against the face of bullying perfection. As every antagonist in the trilogy does, they allow Pegg’s characters to come to terms with their imperfections and use all the free will they have to have their voice heard. Disappointed with Gary’s insistence that human beings just want to be free and go wild instead of getting a cosmic upgrade, the Network enacts its own “scorched earth policy” before departing. Humanity is sent back to the dark ages as the earth suffers some form of destruction and is depleted of its technology.

The Real World

It is here where the Cornetto trilogy realises its ultimate ambition. The world that was dominated by controlling entities and governments is no more, and is now made up of individuals who have free will, and are no longer acquainted with materialism and social hypocrisy. There may be prejudice, strife and the very primal nature that permeates our souls, but there is no hierarchy to stop anyone from making a difference and fighting for their humanity. Everyone has no choice but to engage with one another, and learn to co-exist and survive together.

Gary’s mates go on to mend their problems (Andy’s marriage is saved) and fulfill their desires (Stephen gets together with his school crush), whether as humans or as blanks (in the case of O-Man and Peter, who becomes a better father and more courageous man). In the end, so does Gary. Assembling a few blanks, who stand in for his old gang, he finally begins his life, by embarking on a quest. The world becomes a version of what he always envisioned, which has allowed him to do away with the alcohol and become sober for the first time.

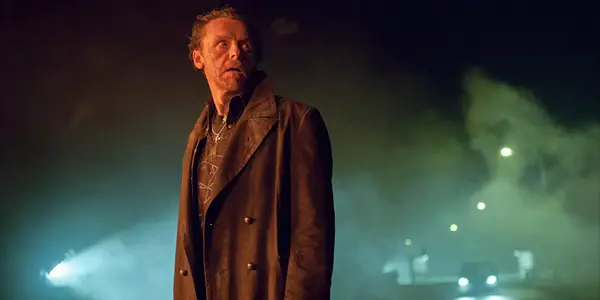

Venturing into a tavern in the middle of the apocalyptic wasteland (that references the Mad Max films and various 2000 AD comics), Gary orders waters for him and his comrades. Disappointed to see that the tavern owner won’t serve blanks (who have become the second-class citizens of the world after the Network abandoned them), he purposely antagonises all the weapon-wielding bar patrons. Gary, lit up from behind by the blue light of the blanks, tells the owner, “They call me the king”. Then he strikes.

All he ever wanted was to create his own legend, mythology and establish an iconography that matches that of any character from comic books, folklore, literature or religion. While the Network practically gave humanity something they didn’t realise they wanted, Gary got exactly what he wanted. And now he gets to reveal his true colours, by unleashing chaos upon an anarchic world, and signifying that deep down he never truly changed. In another distortion of a classic myth, Gary fulfills the prophecy of King Arthur that states that he would return in the future to reign over his land.

Rex quondam, Rexque Futurus. He has become the Once and Future King. And there is no one to stop him.

The Cost Of Freedom

With the trilogy beginning with George Romero, ending with George Miller and always smiling at George Orwell, it does ask a very significant question: What is freedom and how much of it is enough?

Pegg and Wright argue that the idea of a paradise or utopia is a myth, and that we are always going to exhibit a blood-thirsty approach to our individuality and in maintaining law & order, no matter what stage or state of civilisation we exist in. Be it a world that is constantly monitored and patrolled by sentinels and spies, or one where everyone is free to live out their own fantasy, there is no ideal solution to cure the human condition, and it isn’t clear as to whether our inhibitions and ruling entities are here to damage us or protect us or both. We are always one step away from destroying the barrier of civility that turns us into wild animals or zombies, and always met with condescension and disdain by a “superior” alien race, gods, or even by our own kind who maintain positions of authority and influence and feel entitled to treat us like garbage and slaves.

The films are deeply absurdist, and demonstrate that humans simply don’t know what they want, and are constantly on a quest to fill the void and overcome obstacles of their own design, despite their futile existence. No matter how we try to live our lives or distinguish right from the wrong, we can always count on a cornetto to give us brain waves.

What do you think of the films’ and protagonists’ philosophies in the end? Do you agree that humanity is doomed to failure no matter how accomplished they deem themselves to be? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

I'm a film journalist and independent filmmaker who fell in love with cinema at a young age. I also love writing about comics, literature, podcasts, television and video games. I'm just as content watching a movie about a giant killer pig terrorising the Australian outback as I am with one that features a catholic priest in crisis.