Identifying The Self In Christopher Nolan’s MEMENTO

Tim Brinkhof is a Dutch journalist based in New York.…

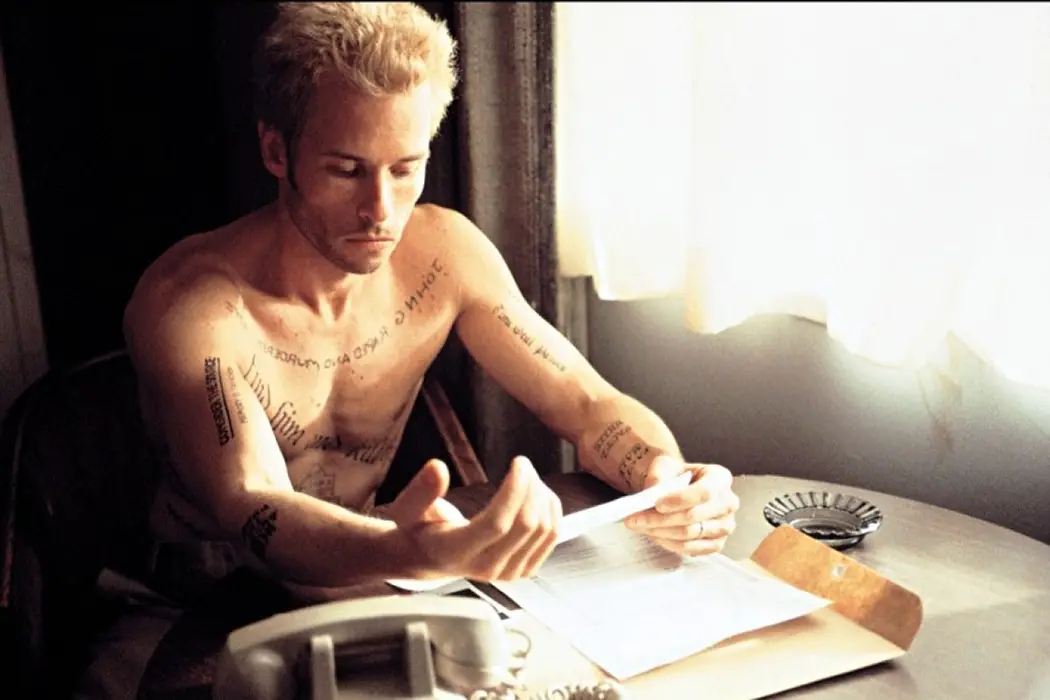

“I have to believe in a world outside my own mind,” Lenny, the protagonist of Christopher Nolan’s Memento, says as he drives off to get his next tattoo in the very last scene. What the hell did he mean by that?

Thinking Backwards

In spite of what the Memento‘s legacy and promotional material may tell you, Lenny’s problem does not concern memory so much as it does truth, and in this respect, he shares his worries with French philosopher René Descartes who, in his Second Meditation, found himself in a pretty similar situation as Nolan’s unfortunate amnesiac. While Descartes admittedly did not suffer from short-term memory loss, he was just as unsure of his surroundings as was Lenny. Believing he was forever unable to perfectly validate anything his senses tell him, he concluded the only thing he knew to be true—i.e. existing—was his own, thinking self: “What then am I? A thing which thinks. What is a thing which thinks? It is a thing which doubts, understands, [conceives], affirms, denies, wills, refuses, which also imagines and feels” (135).

Before Lenny’s story ends, Memento seems to go down a similar road. Upon learning he already killed the man who raped his wife as well as being confronted with the possibility his wife was never raped, but killed by an insulin overdose which he himself administered and realizing (again) that he will never be able to enjoy his revenge, Lenny willfully alters his memories so that he can create for himself another imaginary culprit: his friend, Teddy. While there’s a lot to say about this sequence, I think it clearly reaffirms Descartes’ notion that the thinking, feeling self holds authority over the external world, which it can—in this case literally—shape in its own image.

Identical Diversity

In his essay, On Identity and Diversity, John Locke tries to figure out what can make two things be considered identical. First off, he rejects the popular notion that this is matter. As a seed develops into an oak, the amount of matter that makes up the organism changes over the course of time. If it’s not the amount of matter, then maybe it’s the form. That, after all, does not change, for the seed and the oak can both be classified as a sum of parts whose collective aim is to produce life. The only reason form does not constitute identity is because it cannot distinguish between individual oaks, each of which has, of course, the same aim.

This supposition leads Locke to conclude that the thing which determines identity is consciousness: a reflecting, self-reflecting consciousness. How this definition applies to a plant is a bit tough to grasp, but we understand it more readily when we look at how it relates to human beings. As a child develops into an adult, its body mass changes, but its consciousness remains the same. Similarly, invasive surgery or horrible accidents might completely alter the form of the body, but the consciousness still remains, recognizing itself as one and the same before the critical event in question. The key to Locke’s consciousness here is memory, for, if the consciousness is not able to remember its previous iterations, can it still be considered the same?

Memento begs us to ponder the same question, which it rephrases as follows: Is Lenny, despite not having a short-term memory, the same person?

When attempting to answer this question, it’s important to note that Lenny still has access to his long-term memory. While he cannot make new memories, he knows his name, his childhood, his marriage, and therefore in this sense cannot truly be considered a different person from scene to scene. However, it’s fair to say that his personal journey is severely (if not indefinitely) stunted because of his brain injury.

Remember to Forget

One thing I personally found interesting when viewing the film was the fact that Lenny, who claims to have lost only his short-term memory, forgot that his own wife, with whom he spent many years, was diabetic. I think this detail is important when differentiating between the ways in which Locke and Descartes both regard the self. Though the difference is minor, Descartes downplays the importance of memory. Following the Socratic tradition which perceives the soul to be something immortal rather than bound to any physical body (like Locke’s consciousness), he regards the self as being somewhat permanent and unchanging.

We can see this, too, with Lenny, whose short-term memory loss cannot (as much as it wants to) alter his most fundamental personality traits. If anything, his willfully changing his own memories—an act which he himself will eventually forget—stands testament to the fact that the soul of man is not dependent on its own history, does not move forward or backwards in time, but merely is.

What are your thoughts?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Tim Brinkhof is a Dutch journalist based in New York. He studied history and literature at New York University and currently works as an editorial assistant for Film Comment magazine. His writing has been published in the New York Observer.