Human Rights Watch Film Festival 2019 Part 2: THE TRIAL OF RATKO MLADIĆ, ROLL RED ROLL, ESTA TODO BIEN, EVERYTHING MUST FALL

Musanna Ahmed is a freelance film critic writing for Film…

The latter days of the Human Rights Watch Film Festival 2019 offered more essential worldwide stories, including documentaries about an international war criminal brought to justice, rape culture in the USA, the humanitarian crisis in Venezuela and the fight for free education in South Africa.

The Trial of Ratko Mladić (Robert Miller and Henry Singer)

Is there a more despicable individual in contemporary history than Ratko Mladić? The Butcher of Bosnia was trialed at the Hague for two counts for genocide and five counts against humanity – prosecution, murder, deportation, execution and inhumane forcible transfer of the Bosnian Muslim population. You almost want to turn this documentary off straight away after hearing the blood-boiling details.

The Trial of Ratko Mladić is a fine primer for less informed audiences primarily interested in seeing a straightforward visual progression of the trial, handily condensed from six years to 100 minutes. For those who already know the deets, there’s little to gain in reaching into the complexity of the case or the character. If a narrative, of which we know the outcome, should be about the journey and not the destination, there’s seldom any tension here, whether artificially created or organic, to surprise or supplement how we feel at the outset.

However, some useful viewpoints from the legal team and witnesses on both sides are enough to justify the viewing. This is especially the case when listening to the General’s defense lawyer, Branko Lukic, who contextualizes his defendant’s war crimes by detailing the WW2 history of Yugoslavia when it was occupied by Nazi Germany. Serbs were rounded up and put in concentration camps, supported by Croatian fascists and Muslims sympathetic to the cause.

Lukic concludes that Mladić’s crimes were an act of revenge and a sad continuation of Bosnia’s bloody story. His words aren’t sympathetic – especially when he cries about this case being an opening of old wounds – but his pessimism at the cycle of violence is a crucial sentiment. Co-director Henry Singer’s strongest works – 9/11: The Falling Man and The Blood on the Rose – were fascinating because of their investigative nature into emotional and logical responses of the subjects at the centre of them, and Lukic’s perspective lends The Trial of Ratko Mladić the same quality.

“It’s so important that these war criminals face trial whilst they are still alive”, says a member of the prosecuting team, distilling the importance of this documentary to its basic essence. Filmmakers Singer and Rob Miller captured footage over five years; there was a lot of evidence out there that needed to be gathered in one place, several of the disturbing articles and stories are both shown and heard by the victims.

Overall, whilst I’ll say my viewing experience was affected by pre-existing knowledge of the court case, I felt that The Trial of Ratko Mladić was an ideal fit for the Human Rights Watch Film Festival because it captures one of the greatest stories of justice in human rights by following key figures up-close and presenting the court proceedings in a lucid, digestible way.

Roll Red Roll (Nancy Schwartzman)

Establishing shots have seldom been more disturbing as they are in the opening of Roll Red Roll. We see an idyllic American suburb at night which is subsequently completely ransacked of its private spatial protection as we hear audio of a college kid saying, “That girl… she is so raped right now. Dead body.” If that’s not foul enough, it gets worse a few seconds later when his friend giggles and declares, “This is, like, the funniest thing ever!”

Set in Steubenville Ohio, back in August 2012, Roll Red Roll is a documentary that focuses on the aftermath of a teenage girl’s sexual assault by two members of the high school football team. The implication is far wider than anyone imagines, with students, teachers, coaches and parents all sharing the responsibility of wrongdoing. This story is truly exemplary of a disgusting culture in which the rape victim is disparaged and the rapists are safeguarded.

Thankfully, there are people like crime blogger Alex Goddard out there. She put this case under scrutiny and uncovered chilling evidence on Twitter. As explained in Bellingcat, which premiered earlier in the festival, social media is providing a new basis for evidence in cases and shouldn’t be ignored as a tool for investigations. Considering recent examples – famous ones including James Gunn and sympathizers – the assailants’ social media history may have been examined if the crime was committed today, but in 2012 media outlets weren’t paying attention to the tweets and Instagram images which were posted by partygoers. Goddard captured these vile posts and exposed the posters on her website.

Her efforts gained a major endorsement when Anonymous got involved and alleged that there were more parties involved beyond the two football players, and published the video of which we heard the “dead body” audio. A major escalation soon happened and, just when you think justice has been served as the boys are found guilty, the final act of the film is a scathing document of an uglier aftermath. The message is simple – do not protect rapists at the service of reputation. It doesn’t matter how many sympathizers there are, the truth will come out. Even the local police come under for fire for protecting the football programme.

Towards the start of Roll Red Roll, we hear the girl get blamed by a local radio host (and others) for “drinking too much and being too promiscuous”… how do they not understand consent? Maybe it’s having too much faith in humanity, but I’m optimistic about Roll Red Roll making an impact – as Alex Goddard says in her final words for the film, “People are still mad and talking about it, so I think that things can change.” However, it already looks like it’s being decried in various parts of the internet by a loud minority who are review bombing it with no regard for the filmmaking, simply attacking Nancy Schwartzman’s principled intentions.

As a cinematic experience, the director resembles her film like the recent screen-focused thrillers (Searching, Unfriended, etc), utilising the tracking of a mouse as it goes down the internet rabbit hole. It’s a dynamic form of storytelling with novelty (for now) and the difference between what we see online in this documentary versus the example fiction features is that everything here is real. Roll Red Roll is a vital true-crime thriller for the digital age that matter-of-factly evidences the chilling complicity in the Steubenville rape case.

Esta Todo Bien (It’s All Good) (Tuki Jencquel)

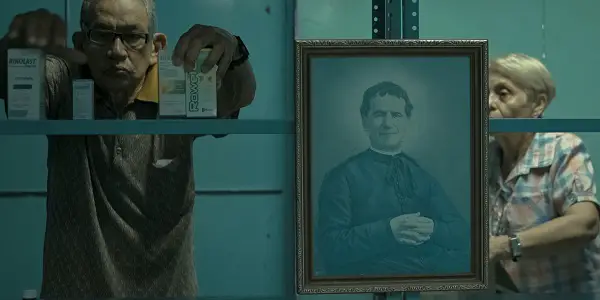

There’s a scene in the ironically titled Esta Todo Bien where elderly pharmacy owner Rosalia Jerez de Zola breathlessly utters to her husband Carlos about the reality they live in, a Venezuela that doesn’t afford them any money or medication to sell and no pension for a safety net, so she feels she has little choice but to give up the pharmacy and rent it out, using those funds for them to stay afloat. She ejects her feelings so fluidly that her monologue almost sounds scripted, but there’s no doubt that her ability to go off like this comes from a long time preparing for such a conversation.

This mournful documentary opens by capturing Rosalia heartbreakingly informing a stream of customers that she doesn’t have what they need, directing them with geographical precision to the other pharmacies that may be able to fulfill their prescriptions. We’re informed that 16,000 doctors have left the country and salaries peek at twelve dollars a month during this collapse of the public health system in Venezuela. Esta Todo Bien looks at this dire chapter of the country’s history by following Francisco, Rebeca, Efraim, Rosalia and Mildred, five citizens affected in their own ways who are all joined together in their efforts to achieve stability.

Filmmaker Tuki Jencquel frames his subjects in a semi-directed way – one that’s becoming common in the medium since Joshua Oppenheimer showed how effective it was – and that’s to place them in a shared space and guide them to re-enact and discuss their experiences in their own creative ways.

These individuals know even as much as the transport routes and weights of the deliveries, gathering every modicum of knowledge they can in order to stay proactive about their own health and that of their fellow citizens. It doesn’t take long for us viewers to be stunned at the realisation of how much we take our healthcare service, and its seemingly unlimited medication, for granted.

The HRWFF’s unexpected promotion of social media as a tool of power and progression bubbles up again when a radio host speaks about Twitter being the place to find medicine because there’s a great solidarity between people using the social network in Venezuela. However, another thing you see online is a lot of conservatives patting themselves on the back as they point to this case as the failure of socialism. Above the ideas of democracy, we desperately need compassion to be far on top of anything else in this conversation. Esta Todo Bien is wretched but necessary viewing.

Everything Must Fall (Rehad Desai)

The story of how #FeesMustFall came to be is a culmination of the worst obstructions to a progressive society – racism, sexism, capitalism, classism, patriarchy, homophobia. Rehad Desai’s utterly incredible documentary Everything Must Fall is a bible for the student-led movement in South Africa that fought for, as Shaeera Kalla, former Student Representative Council President of Wits University, wrote, “The demand for free, quality and decolonised education.”

The #FeesMustFall protests targeted the people in power who were increasing the cost of university fees (rising an astronomical amount over the 21st century) and the government that wasn’t doing anything to offset the imbalance by insufficiently funding the universities.

The University of Cape Town, Rhodes University, and many other universities across the country participated in protests but, weighing the epic scope of the movement with concise cinematic storytelling, Desai chooses the University of Witwatersrand as his primary case study, where the movement was founded by the aforementioned SRC leader Shaeera Kalla. She is the predominant interviewee for this film, which also features other student leaders, activists, university workers, and Wits’ vice chancellor Adam Habib, whose shoulder-shrugging reconciliation of personal politics (once a leftist student activist himself) and professional compliance (calling 1000 policemen to the scene to distressing effect) clashes with Kalla’s relentless tenacity.

There are several elements to Desai’s filmic construction that makes Everything Must Fall utterly captivating. For starters, the narrative is slickly depicted in chronology. Another is the quality of the interviews and how they create a three-dimensional view of this momentous chapter of recent African history, giving us a strong understanding about who, what, when, where, why and how this all came to be. The whole circumstance is haunted by the spectre of Blade Nzimande, former Minister of Higher Education, whose actions – or inaction – contributed to this outcome. He declined to be interviewed for this film.

A strong engagement with intersectionality furthers the value of the director’s examination. Kalla speaks on gender and religion within the student groups, reflecting on the importance of social justice in Islam and the difficulty of being a female leader – the result of fragile masculinity. Women are at the forefront of the movement, and whilst there are allied male leaders such as Vuyani Pambo, a fellow student leader who says “There is no membership to the struggle” regarding superficial differences, there has been infighting born out of the patriarchy.

Without good production, a filmmaker can damage the effectiveness of their message, and Desai’s terrific choices keep our attention transfixed throughout a fast-paced 90 minutes. There’s no indulgence or sidetracking; I only named two of the key contributors above but every interviewed individual speaks from a significant perspective, not simply endorsing existing points. The actuality footage of the protests is absolutely outstanding – an astonishing sequence of a protestor standing up for the right just to cross the road which soon escalates to gun shots for no discernible reason, leading him to be restrained, is one such example. There are very real examples of the injustice for us to see for ourselves, like the image of a large number of black students who line up for free meals.

Everything Must Fall is an enormously powerful film about a cultural revolution, featuring startling footage from the ground level and a riveting series of interviews from essential figures. I’m reminded of the Oscar-nominated The Square, another brilliant documentary about protesting for change, and I hope Rehad Desai’s film receives similar attention, though that may be difficult because his film is so (necessarily) unflinching. It’s is an essential document, brilliantly assembled to help us understand such a colossal event.

Most documentaries at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival 2019 have greatly considered history and Everything Must Fall shows the regressive result when the worst ideologies in a nation’s history pile up, and the response from revolutionaries who want a better future for themselves and the next generations. This was a terrific choice to close a festival that highlights critical global voices through the work of amazing filmmakers around the world. I look forward to next year’s edition of the HRWFF.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Musanna Ahmed is a freelance film critic writing for Film Inquiry, The Movie Waffler and The Upcoming. His taste in film knows no boundaries.