Horrific Inquiry: KAIRO (2001)

Stephanie Archer is 39 year old film fanatic living in…

Welcome back to the newest, and at times goriest, column here at Film Inquiry – Horrific Inquiry. Twice a month, I will be tackling all things horror, each month bringing two films back into the spotlight to terrify and frighten once more. And occasionally looking at those that could have pushed the envelope further. Join us as we dive deep into the heart of horror, but warning, there will be spoilers.

Horror films know no boundaries. Horror is found in the recesses of every culture, religion, and form of humanity. It is the fear of the past and the present. Originating as folklores told from word of mouth, it has evolved over centuries to the cinematic form we recognize today. For this month’s final induction, we travel to Japan, where horror, legends, and ghosts are a deep well of horrific material, Kiyoshi Kurosawa‘s Kairo not only terrifying at the time of its release, but finds a nerving relevance to the past year that continues the success of this J-horror classic, but proves that horror of one decade can be as terrifying for another. Celebrating its 20th anniversary this year (and not to be confused with the American Ian Solmerholder remake), Kairo is eerie, haunting, and deeply understanding of the effects of loneliness on the human soul.

Two Storylines Intertwined

Kairo follows a pace that is literally represented by the film’s title. There is a steady heartbeat that flows through the film, a literal pulse that refuses to slow down or speed up. There is a feeling you are experiencing the film in real-time with its characters, just as unable to look away and avert your eyes. The infusion of reality with digital technology is instant, Kairo opening to the all too familiar sounds of dial-up and the sound of a phone ringing. As a woman on a boat, her back to us, begins her introduction, there is an ominous feeling that surrounds her, an unseen presence. She wants to tell us her story, breaking through a perceived loneliness that surrounds her.

As her introduction takes us to the past, viewers are given a stationary view of a room, a computer workstation dark and vacant. The sounds of a phone ringing fill our ears, digital distortion and static break up the phone and the visual imagery. There are no ghosts that instantly jump, just a forced view of the computer and the digital interference that surrounds and fills the space. As the scene holds, the phone ringing unanswered, the film’s initial score begins, its eery notes undistorted, unsettling, and slightly off-key – its sound reminiscent of an Alfred Hitchc*ck classic. In this one forced perspective of a moment, the stage has been effectively set.

The caller, Junko (Kurume Arisaka), begins to become unnerved as the phone continues to remain unanswered, a deadline ahead for a disk that needs to be delivered, and the condition of her friend in question. Michi (Kumiko Asô) decides to go to Taguchi’s (Kenji Mizuhashi) apartment to check on him and retrieve the disk. As she enters the apartment, it is silent and apparently vacant. She shuffles through the disks on his desk and papers, the mise en scène perfect for the appearance of faces and moving shadows. Yet, the tension stays even and steady, unwilling to sacrifice the feeling it is attempting to establish for cheap jump scares. The payoff will come with patience. As Michi continues to search, Taguchi rises from where he was hiding, conversing with Michi briefly and casually before fitting a noose and hanging himself. It is quiet, sudden, and shocking, giving the film’s first death and discovery the perfect air of mystery and suspense.

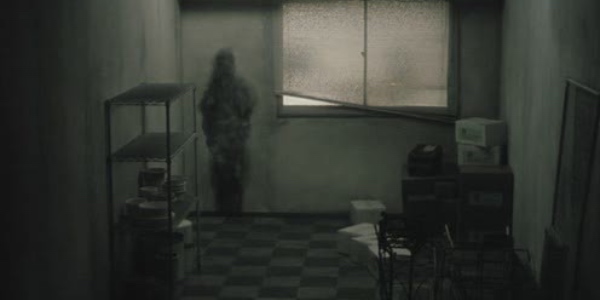

Breaking from Michi and her co-workers, Kairo introduces a secondary storyline, giving more authenticity to the information relayed and discovered, and widening the breadth of effect to everyone involved. Ryosuke (Haruhiko Katô) is an economics student hooking up to the internet for the first time. His naivety means he is not aware of the control he lacks when his computer immediately connects to videos of other solitary individuals in their apartments, sleeping, walking, and sitting around. While finding it strange, he goes to sleep, the computer turning itself back on, a man in a chair with a bag over his head a faceless individual starring back. As Ryosuke awakens, he is understandably freaked out, especially as the man wheels himself closer to the screen and slowly begins to remove the bag from his head.

The following morning, Ryosuke goes to the computer science room to meet Harue (Koyuki), who helps him discover ways he can obtain more information on the site. Yet, as he is pulled further and further within the mystery, he begins seeing ghosts around him, outside of the computer and outside of his apartment. Meeting a fellow student, he comes to the conclusion that souls have begun to invade the physical world, Harue building on the idea that these souls, these ghosts, want to trap humans in their loneliness, rather than kill them. It is at this point, as more and more people begin committing suicide and vanishing, that I find myself thinking about the inspiration this film might have had on M. Night Shyamalan‘s The Happening.

And as more and more individuals vanish, the film falls into an apocalyptic feel, the lives of Ryosuke and Michi crossing paths and becoming intertwined. As they fight back against the souls of those long since passed and try to fight the loneliness, the fear of survival becomes bleak, and the will to live fleeting.

Meaning is in the Eyes of the Beholder

When reading a horror film, there is usually the straightforward face-value understanding, the deeper meanings read through a personal perspective. Kairo can be read in a lot of ways, including when it was released, as a retrospective, and as a present-day application. While there can be read a literal meaning, the vanishing of individuals and the ashes of those who have succumbed to the loneliness speaking to the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, or even a biblical ashes to ashes and dust to dust perspective, Kairo reaches so much deeper in its examination of the human spirit, the technological revolution and even now, in the face of a global pandemic.

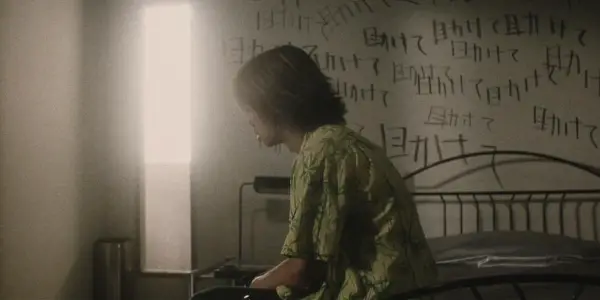

Kairo at its core is a gripping examination of the effects of depression. There is a darkness that follows a person, settling in and looming overhead. There is even sometimes a paranoia of being watched, of what others are saying about you. Those suffering from depression, especially on their darkest days, become a shadow of their former selves, some hiding the pain behind a smile and caring on as normal until they can’t like Taguchi or others unable to leave their beds and fight the loneliness they feel, much like Junko and Ryosuke. Yet, Michi Kairo (Pulse) finds its hope for better days. There is hope that you can fight the loneliness, finding a friend and a way of life that brings happiness, even when the loneliness lingers just out of reach. There is hope to push through and still live a fulfilling life without the darkness.

2001 was a time of transition. The world wide web had been introduced in 1990 and had spread through the world like wildfire. The fear of its power and reach would divide a generation coming of age and generations that came before. As many embraced the new technology, others turned from it, unwilling and fearful to adapt to the changing times. As with changes in the timelines of humanity, a drastic change draws new superstitions and fear, all while slowly merging older ones of the past with the present. Here, the idea of souls entering the digital world and gaining control evolves the ghost stories told around campfires and told to children to curb behaviors. And through the evolution of ghostly possessions, also brings forth the fear of artificial technology, the loss of control by and eventually perceived extinction of the human race. One of the students at the school speaking of the ghosts in digital form gaining strength states, “once it is done, it will function on its own.” Here technology is the force that divides the masses, treated as a vacuum of solitude and seclusion, and threatens to one day be in control.

Watching Kairo a year into a global pandemic was eerie, heightening the effect of the film. With each new person the souls are able to reach, whether it be through TV, phone or computer, it spreads like a virus. And as each person is placed within their own suffocating and agonizing bubble of loneliness, there is a feeling that Kairo, in its own form, is happening now. And it spreads. The loneliness spreads, the internet, video, and phone the only means to communicate. We are the individuals each in our own rooms, sitting, sleeping, and pacing, others looking in through their Zoom calls – whether it be work, family, or loved ones. There is a concern for the current and post-pandemic mental health that could result from the extended quarantines and lack of socialization. Much like the horror of the souls, the effects of their digital possessions were far-reaching, each person experiencing their own horror, so too was COVID-19 and the quarantines enacted to fight it.

Conclusion: Kairo

Kairo is the first of many J-horror films for me, and one I am thrilled that it’s my introduction. It is deeply enlightening, haunting, and unbelievably relevant 20 years later. While its effects may not have held up, the effect of the film and its story does, still molding and evolving to strike a chord in 2021. If you are looking for an old classic or a new horror love, make Kairo a must-see.

Have you seen Kairo? What did you think? Let us know in the comments below!

Watch Kairo

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.