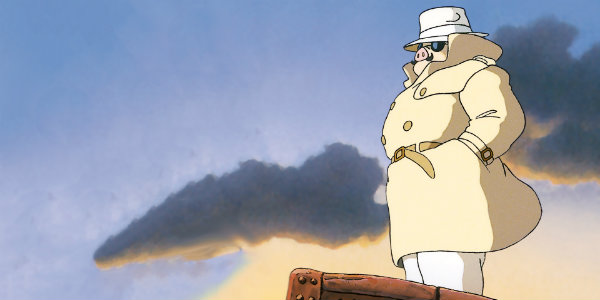

Marco Pagot is haunted by the memories of a war since passed. Veteran-turned-bounty hunter, Marco is immortalised in Hayao Miyazaki’s film Porco Rosso (1992) – his steely-eyed, wounded nature reveal more about his experiences and about his pain than a quirkier and more compulsive figure ever could. He commands a respect that he does not invite, says what needs to be said, refuses affection or companionship.

What he has seen in the war, what he has had to do, are left unsaid but implied with the simple mannerisms he exhibits. And, because this is a Hayao Miyazaki, Studio Ghibli produced production, Marco Pagot is also a talking pig.

There is brief reference to the reason for this in the film, something about “a curse”, but this explanation does not ring true. The narrative force of the film is not for Marco to lift his ailment and become human again, rather, the force of the film is derived more from Marco’s seeming insistence that he is better off this way. As he points out, “I’m a pig. Laws don’t apply to me”. His form represents a freedom from authority yes, but perhaps also showcases a rather tragic disassociation from his own kind, after seeing the shame of the war, having coated himself in that shame by taking part.

Finding Honour in Solidarity

The currency of honour is what drives Porco Rosso the movie, but is it what drives Marco Pagot the character? Both heroes and villains in the film are trying to capture that illusive idea of honour, either from challenging Marco to duels, as in the case of Donald Curtis the American, or to the sea pirates who, despite capturing children as hostages, effectively allow said children to take control of their aircraft, such is their unwillingness to cause them harm. Even Madame Gina displays a modest sort of honour by waiting patiently for Marco to come and marry her, something which does not culminate during the film, and may not culminate after it either.

Marco displays honour but is reluctant to show passion; his honour is one borne from the traumas he has experienced and the faith that he has lost in humanity, a humanity that he has physically left behind. Honour is the currency that everybody wants in Porco Rosso – Marco has plenty but nothing to spend it on.

The trick that Porco Rosso pulls off so effectively is that it effectively translates a narrative about war, grief and heartbreak into a picture that is so immediate in its colour and its warmth. The film is bursting with humour and life from the very beginning – a mass child-kidnapping is turned into brilliant physical comedy, and a climatic duel between two fighter pilots is quickly shaped into a hilariously stubborn fist-fight in shallow water. The skillful silliness of the animation and the comedy only makes the trauma of the film more impressive, and it is that trauma that is so readily there for an audience, if they are willing to find it.

Mirror Images of the Same Man

That trauma is bursting out of the film for those who wish to discover it. For a fighter-pilot-talking-pig of a character, Marco is hinted to have extreme trauma dating back to his time in the war, and his cool, effortless honour is expressed through weariness rather than bravado – his natural contrast is Donald Curtis, the American fighter pilot who is desperately after Gina’s heart and sees Porco as the obstacle that keeps him away from her. Curtis is slender, handsome and full of an Americanised style of heroism – c*cky, machoistic. It is no surprise that in the film’s epilogue he is shown to have gone on to have a successful career in Hollywood.

The film has respect for both Marco and Curtis certainly, but in a sense that Curtis only derives respect through his similarities to Marco. Curtis feels like a version of Marco that avoided the traumas of past lives, a Marco that expresses his honour through charm, through boastful means, rather than in Marco’s more obviously damaged way. Curtis feels younger, more desperate to show off his skills and to win the girl, whereas Marco is deliberately fighting against love, against happiness that he doesn’t feel like he deserves.

Images of War Bleeding Through

In the Roald Dahl short-story ‘They Shall Not Grow Old’, a fighter-pilot in World War II has a surrealistic, heavenly experience where he is given a peek into the afterlife; of bursting through white cloud to see a line of planes, as far as the eye can see, stretching off above him. This idea is, to use the word tentatively, ‘borrowed’ in Porco Rosso, as Marco remembers a glimpse into the deathly horror of the afterlife that he experienced while in the war. The visualisation of Dahl’s idea leans into the cosmic surrealism of the original vision – the line of planes in the sky originally resembles a sea of stars, until Marco looks closer to see the vast shimmering constellation of fallen comrades.

This is a truly alarming sequence for the film to suddenly present, and one that excellently ties together the world of the comical and the world of horror that is to be found behind the curtain. It not only briefly brings Marco the man back to the screen, seeing his human reaction to this vision of the afterlife, but also brings his trauma to the front of the film. We are no longer given the opportunity to ignore his plight and his trauma – his usual mask to hide behind, his ‘curse’ of being a pig, is stripped, and this is a mask that both he and we, the audience, have been using to ignore the suggested horrors of the narrative. This sequence shows us Marco’s trauma and, even if it is only a brief sequence in a much larger picture, this trauma resonates and colourises the rest of the movie. When, at the finale of the film, Marco purposely rejects the love of two women, we are, thanks to this sequence of surrealism, not at a loss as to why.

Accepting the Love We Think We Deserve

Often with Miyazaki’s films, such is their nature in being children’s films, a satisfying conclusion is the least that you can expect. This ranges from something as lightweight and deliberately simple as My Neighbour Totoro to the more visually and narratively complex Spirited Away; with such charmingly animated and feel-good children’s films, a happy ending is the least that the audience expects, the least that they feel they deserve.

Comparatively, Porco Rosso ends in a bubble of bittersweet uncertainty. All the characters are given their own little epilogues and endings – Fio becomes an extremely successful aviation company manager, Curtis becomes a Hollywood actor and all of the members of that lovable pirates federations continue their lives happily into old age. The only two characters whose fate remains uncertain are arguably the two most important, Marco and Gina, whose futures are left unclear. With the knowledge gained that Gina loves him, did Marco finally end her long wait for his affection? Did Marco permanently transform back into a man after Fio’s kiss, leaving his trauma behind, or was it simply a temporary reprieve from the curse? As a Hayao Miyazaki film it is often good to remain optimistic, such were undoubtedly the intentions of the man himself, but the uncertainty of the final images remain a bittersweet reminder that love isn’t always as perfect or as simple as Hollywood would allow us to believe.

Ultimately, Marco has demonstrated an inability to love or, more accurately perhaps, an ability to accept that he deserves it. There is a poignant reminder right after the credits that Marco is still out there, as his red plane flies past the camera and disappears into the clouds one last time. Whether he and Gina found love together remains their secret, and in allowing them that privacy Miyazaki demonstrates a remarkable maturity and respect that perhaps the characters in his other films aren’t always given.

It is quite something to give two fictional characters (one of whom is a pig) the ability to keep their love and futures a secret from the audience, but Miyazaki gives it here in this, perhaps his most remarkable of pictures. Porco Rosso is a film beaming with silliness and warmth, while also being tied and grounded in a particular human timeframe like very few Miyazaki movies can boast to have. It is a movie that not only stands up as one of Miyazaki’s most adult and traumatic pictures but also one of his funniest, and this gives it a basing in the realms of reality that not even a large talking pig can hope to shatter – Marco, with the trauma hiding behind his eyes and heart, is perhaps Miyazaki’s most breathtakingly human creation to date.

To me the film’s ending remains desperately bittersweet through its longing and uncertainty, but I love that tiny glimpse of that red plane flying away at the end. It is a reminder that, despite heartbreak and war and terror, that good people are, and always will, be there, beyond the clouds.

What do you think of Porco Rosso, is it truly Miyazaki’s most underrated film? Let us know in the comments!

Watch Porco Rosso

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.