HARRY POTTER Should Have Been A Television Series

Hazem Fahmy is a poet and critic from Cairo. He…

Since its debut back in 2011, Game of Thrones has proven to be a monumentally influential force on the screen. In addition to breathing life into the mature, sprawling epic, it usurped cinema as the optimal, go-to medium for fantasy adaptation. Films adapted from fantasy novels and series are of course still being made, but the prowess of Game of Thrones has, on the one hand, sharply raised the stakes for the quality of fantasy on the screen, and on the other, demonstrated the power of television in realizing a beloved, lengthy series.

Just last month, a Birth.Movies.Death. review of the mediocre Dark Tower adaptation discussed how it should never have been a film at all, rather: “another ongoing HBO event series, a format that would have allowed its showrunners to tease out the series’ many mysteries and wander down its various alleyways, building the world as it went.”

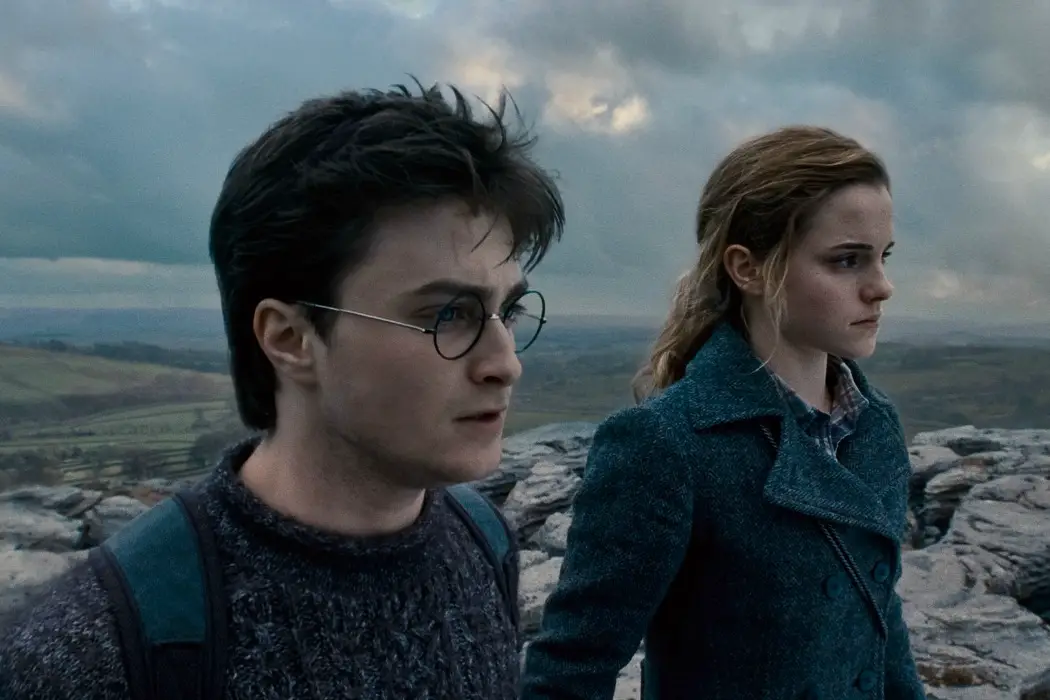

Such, I believe, should have been the fate of the Harry Potter franchise. The eight films, despite their tremendous financial success and worldwide fan base, have always felt severely uneven to me; thriving in regards such as performance and production design, yet lacking in cohesive and consistent world building. Even Alfonso Cuarón’s The Prisoner of Azkaban, widely and justifiably considered to be the best film of the franchise, fails to adequately capture many of the essential joys and horrors of J.K. Rowling’s third installment.

This issue is far larger than individual directors’ visions or even studio intervention (though Warner Bros. certainly had its fair share of mishaps with the franchise) rather, it boils down to the very structure and ethos of the Harry Potter saga.

Hogwarts is Where the Heart Is

Talk to me about Houses and Dark Lords all you want, Harry Potter was always, first and foremost, a coming of age story, and a phenomenal one at that. Though Voldemort provided a thrilling villain whose campaign of terror often drew fascinating real-life comparisons with fascistic and ultranationalist European movements, he was never exactly what made the story unique.

The war against him and the Death Eaters may have been the driving force of the plot, but the emotional core was much simpler and, frankly, far more profound: we follow a young boy, seemingly rejected by the world, as he learns to carve his place in it, finding compassion and camaraderie on his way. This theme is by no means ignored in the films, but it has a much harder time coming out. The length of the average feature film is simply not sufficient. In contrast, a television adaptation of Harry Potter would’ve allowed its makers to focus on the story’s single biggest strength: the Hogwarts academic year.

Those of us who were Harry Potter fans as children didn’t run around roleplaying Auror; we ran around roleplaying Quidditch (now its own sport), potion making, and charm casting. While grand battles between good and evil are, to an extent, exciting for any age, there was nothing more thrilling for a kid than an invitation to reimagine the trite academic space as a literally magical one. If we look away from the generic conflict, the books actually gave us a bold new way of looking at a fantasy world; one in which magic was something to be learned, practiced and evaluated on; in which a society’s fantastical qualities did not save it from mind-numbing bureaucracy and oppressive, hierarchal forces such as classism.

When we look back on this world that so blew our minds back in 1997, we can’t help but think: of course there’re brands and big banks in the magical world. This kind of world-building, I’d argue, is much richer than that of The Lord of the Rings or The Chronicles of Narnia. Rowling’s fantasy is one spun out of reality, and that is exactly why we continue to find it so feverishly endearing.

TV vs Film

Though I love every single book in the saga, The Half-Blood Prince was always my favorite. Of all the titles, even The Deathly Hallows, none do as much to showcase the richness and complexity of Rowling’s world as the sixth does. In addition to an imminent war, Harry and Co have to deal with standardized testing, ever-more complicated love lives, and the existential dread that accompanies one’s coming of age.

This is of course not to mention Harry’s superb history sessions with Dumbledore, easily some of the best narrative and dramatic use of exposition in fantasy. In contrast, David Yates’s adaptation of The Half-Blood Prince is by far my least favorite of the franchise (yes, that includes The Deathly Hallows Part 1, thank you very much). Despite its many merits, the stellar cinematography and the haunting score especially, the film simply failed to capture the ethos of Harry’s sixth, and last, year at Hogwarts.

I’d argue this wasn’t so much Yates’s fault as it was a simple matter of medium incompatibility. Virtually every arc in The Half-Blood, whether it be Harry’s relationships with Ginny, Slughorn, and Dumbledore, or Hermione and Ron’s developing romance, or Draco’s mysterious plan etc., depends on a kind of narrative longevity that a feature film simply can’t provide. With all the compression and cutting it does, the final theatrical cut of The Half-Blood Prince was still over two hours and a half.

But this isn’t just a matter of time. The nature of feature filmmaking, especially the Hollywood Blockbuster, discourages the repetition of space and situation, opting instead for a dynamic flow of events and a constant change of environment. This is problematic for a saga that mostly takes place in one school, and whose characters are heavily shaped by the academic and extracurricular routine of said school.

Harry Potter For TV: Conclusion

Television on the other hand thrives off of revisiting and developing space and situation. A Harry Potter television series could have taken its sweet time exploring the characters’ relationship with the phenomenal space that is Hogwarts. It could have allowed their friendships and romances ample time to blossom and change. It could have centered day-to-day life at Hogwarts as the dramatic focal point of the story, and not the generic Wizard War. Here’s hoping Warner Bros. takes not if they ever make that Marauders prequel.

What film franchise do you think should have been TV?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Hazem Fahmy is a poet and critic from Cairo. He is an Honors graduate of Wesleyan University’s College of Letters where he studied literature, philosophy, history and film. His work has appeared, or is forthcoming in Apogee, HEArt, Mizna, and The Offing. In his spare time, Hazem writes about the Middle East and tries to come up with creative ways to mock Classicism. He makes videos occasionally.