I first became aware of Harry Chapin in my high school Psych class through a discussion of his most iconic song “Cat’s in the Cradle.” The lyrics were derived from a poem by his wife Sandy about a father who never made time for his son, and it comes back to haunt him. Chapin gladly stole the words and turned them into a catchy, strikingly poignant tune on parenthood.

Since then, “Cat’s in the Cradle” really took on a life of its own. In fact, it’s become a part of the cultural lexicon showing up in everything from Modern Family and The Simpsons to Shrek the Third. It struck a chord with listeners and remains relevant years later.

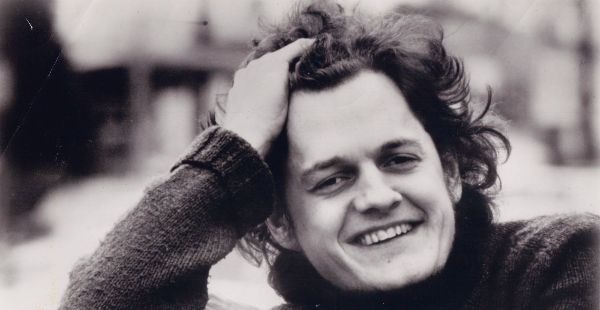

Harry Chapin is one of the all-time great story song performers because his humanity came through every line he ever shared with his audience. Tunes like “Taxi” or “Mr. Tanner” capture these profound intimacies about human relationships and the human experience. Whether real or imagined, there’s this irrefutable truth in every one of their lines. Chapin will no doubt be remembered for this if nothing else.

However, if you are looking for an all-encompassing musical documentary, Rick Korn‘s exploration is only partially interested in his musical career, and this is on purpose. Although he is gone now, one would suspect Harry Chapin, would have been pleased with the focus on the great passion of his life: alleviating world hunger.

It sounds almost ludicrous. How does a singer with a guitar and a laundry list of songs, take on a heady, seemingly unfathomable task like world hunger? When you learn about Chapin — his unquenchable enthusiasm and relentless zest for life and the things he believed in — it doesn’t feel all that ridiculous. Moreover, it seems true to his character as a fellow human being.

In fact, it’s Chapin himself who evokes Bob Dylan‘s line from 1965, “He who is not busy being born is busy dying,” and it gives seed to his own credo, which would become the fitting subtitle for this whole project. When in doubt, do something.

Family Roots

It’s an added fascination to consider Chapin‘s own upbringing. He fostered a love of song taking part in choir and piano at the family’s local church. Later he formed a trio with his brothers, Tom and Steve, which was particularly in vogue at the time thanks to groups like the Kingston Trio and The Weavers.

By all accounts, he was not the most talented of the brothers, but he had the winning charisma to connect with people. Between a stint in the military and time as an aspiring documentarian, even being nominated for an Oscar in 1968, he came back around to music. Eventually, he tooled his craft on stage and put something out into the world as a solo artist.

Some of the talking heads that show up, along with lifelong bandmates like Big John Wallace, are other performers who benefited from Chapin‘s generosity. Billy Joel found himself opening for Chapin in the early 70s and some folks even likened “Piano Man” to one of the other musician’s story songs. Chapin also went to bat for Joel, promoting his work and rooting for him. We all know how that turned out.

Likewise, Pat Benatar met Harry Chapin after one of her performances in a bar, immediately taken with Chapin‘s encouraging spirit and his unassuming everyman-ness. After inviting the singer to join one of the public performances he was putting on, she wound up paying for his drink. Because typical Chapin didn’t have any money on him. It’s these types of interactions that help to humanize him for the viewer, although some work better than others. Bruce Springsteen winds up sharing his own well-meaning anecdote during one of his shows that’s stretched out throughout the length of the entire documentary rather uncomfortably. It doesn’t end up being as profound as it’s supposed to. Still, the thought is there.

Grassroots

Because, after all, this seems to be the most imperative tenet of Harry Chapin‘s character: his thoughtfulness. Perhaps he wasn’t the most punctual or consistent of people, but he made up for any shortcomings with his irrepressible appreciation for communion and sharing in music with other people. But it also extended further with genuine concern for the well-being of others. In his own words, “what makes us unique are human rights, human needs, and human dignity.”

He and priest Bill Ayres formed a formidable partnership, initially over the rock radio waves, and then as the catalysts of a grassroots movement for change. As a Yin & Yang pairing of personalities, they worked tirelessly to advance the fight against world hunger. Taking inspiration from George Harrison‘s Concert for Bangladesh, Chapin went full-throttle, holding hundreds of charity concerts for the cause.

But they took it further. They reached out to the U.N., and they strived for change on Capitol Hill with Chapin working with politicians like Patrick Leahy on the Subcommittee on hunger under the Jimmy Carter administration. Chapin exemplified an admirable endurance, sticking with the issue day in and day out, remaining deeply invested in its progress until his final days. What becomes evident is that while their cause was aided by political avenues, it is not solely a political issue. It feels like a human one.

Conclusion: When in Doubt, Do Something

Harry Chapin‘s daily regimen was staggering accentuating a lifestyle that was hardly sustainable. For most people, these are symptoms of excess and partying. For Chapin, it was due to his generosity of spirit and laissez-faire attitude about the business side of the music industry. He died in a car accident in 1981 going to yet another charity concert because that’s what he did.

If songs like “Cat’s in the Cradle” and “Taxi” are a testament to his lasting influence, his social activism speaks even more loudly. He is one of only four musicians to earn the Special Congressional Gold Medal. It has been awarded to only 114 citizens, among them George Washington, Robert F. Kennedy, and Thomas Edison. The other musicians are the Gershwins, George M. Cohan, and Irving Berlin. To that list add Harry Chapin.

While many (including myself) would probably have appreciated a more robust exploration of his musical career, there’s also a deeply human message embedded at the core of this documentary. By showcasing Chapin‘s indefatigable life, snuffed out far too early, we are given a call to action of sorts. Now, nearly 40 years after his death, he is still having a positive impact on society — through his life-giving music and the tireless groundwork he laid to fight world hunger — work that is still germinating today. Now it’s up to us to respond in kind. When in doubt, do something.

What are your thoughts about Harry Chapin’s music and his career? Please let us know in the comments below!

Harry Chapin: When in Doubt Do Something will be released on October 16, 2020, in theaters and on VOD.

Watch Harry Chapin: When in Doubt Do Something

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.