GULLY BOY: Hip-Hop Empowers Mumbai’s Poorest In Profound Musical Drama

Musanna Ahmed is a freelance film critic writing for Film…

“Hip-hop is the new rock and roll”, Kanye West once famously declared when referring to the genre’s contemporary popularity. Rap has gone from a movement born out of the South Bronx, where disenfranchised youths expressed their creativity through this art-form as an escape from their poverty-stricken, violent and corrupted milieu, to currently the most consumed genre of music in America.

Though the current state of hip-hop is contaminated by hedonism and commercialism, the socio-political commentary and strong storytelling still exists through the current generation’s most accomplished artists such as Kendrick Lamar and J. Cole, as well as in the late works of active veterans, as illustrated by Jay-Z, Eminem and Nas.

The latter example is key to Gully Boy: without physically appearing in the film, Nas casts his presence in the second half of this brilliant coming-of-age drama that centres on a street rapper from Dharavi, a locality in Mumbai and also one of the largest slums in Asia, who gets a shot at breaking free from economic hardship by entering a battle rap contest established by the Illmatic rapper that promises the winner one million rupees.

Gully Boy is co-written (with regular creative partner Reema Kagti) and directed by the brilliant Zoya Akhtar, who, after directing the wonderful Luck By Chance, Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara, and Dil Dhadakne Do, again demonstrates a knack for depicting the facets of love, life and ambition with her energetic and purposeful new picture.

Escaping the slums through music

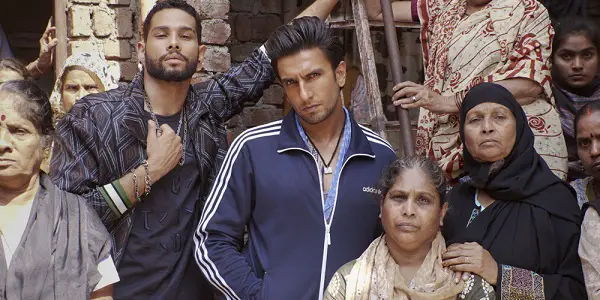

Gully Boy, translated as Street Boy, is titled after the stage moniker that the protagonist Murad Sheikh (Ranveer Singh) assigns for himself and is loosely based on the lives of two real Mumbai-based street rappers, Naezy and Divine, who lent their lyrical aptitude to the writing process by contributing lyrics for their cinematic composite counterpart.

To make ends meet, Murad takes on odd jobs, including chauffeuring for a wealthy family and performing depressingly generic white-collar work. His father is a violent abuser towards his hapless mother and his younger siblings largely fly on the wall as they bear witness to the increasingly bastardized relationship of their parents. It takes time for Murad to gain the courage to stand up for his dear old lady, for his working-class upbringing has made him timorous of authority.

One of the strengths of Ranveer Singh’s brilliant, culturally significant performance is his ability to harness his rage through a simple scowl. Murad’s anger is largely a muted display of impuissance, with the actor surprising us by travelling to a different dimension for emotion compared to his most famous characters – fans of the star would likely suspect him to roar and lash out like Padmaavat’s vicious Alauddin Khilji or Simmba, but are instead led to empathise with the guilt of Indian children who feel isolated when, in their elders’ eyes, defence means defiance.

So, when Murad’s creativity can’t be exercised in the workspace, and there’s no room for big emotions at home, his life-long passion for hip-hop takes center stage when he meets regional bigwig MC Sher (Siddhant Chaturvedi), who sees promise in the young artist and takes him under his wing. Murad goes from writing lyrics in his notepad from the driver’s seat, and listening to A$AP Rocky through earphones when loitering in the slums, to being embedded in the world of battle rap and music videos (which nicely act as little films about the community) thanks to his new mentor Sher. If the premise sounds a bit too familiar – yes, there are strong similarities to 8 Mile.

His palms are also sweaty

The comparisons between the two hip-hop underdog stories are unavoidable. From the protagonist’s engagement with battle rap, to his abysmal domiciliary environment, to his earth-toned hooded appearance – and even a Lose Yourself-ish motif for his formational song Apna Time Aayega (“our time will come”) – 8 Mile is certainly the most obvious audio-visual reference. There are a few story beats that are almost entirely replicated. One such moment is in Muhad’s first rap battle when he suffers the same initial fate as B-Rabbit – the rookie is handed the mic and chokes, unable to utter even a single syllable.

This ordeal plays out unnaturally, considering the aptitude we see in Muhad when he performs to crowds in the scenes immediately preceding this one. This scenario feels like it exists as a manufactured, ‘compulsory’ conflict point rather than an organic development of his character. It’s one of the few missteps in Akhtar’s otherwise brilliantly placed priorities of character over plot, as she mostly succeeds in traversing the landmines in 8 Mile territory for something ultimately different.

Furthermore, regarding character, where the comparisons to 8 Mile are in favour of Gully Boy are in its significantly more interesting characterisations of the female characters. Of course, this success comes from actually having women at the pen and helm.

The tremendously talented Alia Bhatt portrays Safeena Firdausi, a bright medical student in a conservative Muslim family who covertly hides her relationship with Murad from her parents. Their romance isn’t intrinsic to his ascension in Mumbai’s rap scene; she leads her own narrative and their love life is a separate, intertwining entity.

Gully Boy is a spirited work of advocacy for the working class in Mumbai and the two central characters are independently representative of various aspects of that reality. Safeena is subject to controversial conversations around her education and marital status. Her traditional parents want to arrange a husband for her – which dubiously slides into a comedic situation typical in Bollywood – but her priority is to finish her studies and become a surgeon. The on-and-off relationship she has with her hijab exhibits great “show, don’t tell” storytelling by Akhtar to convey Safeena’s commitment to inherited family values, and the societal pressure of geographical and social spaces in which she’s veiled versus where she isn’t.

A star is born

A star is born in Siddhant Chaturvedi, the charismatic newcomer who plays MC Sher, who bursts into a fiery performance in his introduction, lighting up to the screen in memorable fashion. The actor maintains an unparalleled level of charisma, suggesting he’ll be as popular as co-stars soon enough.

Chaturvedi’s standing as a newcomer to Indian cinema works well for his casting as an adept MC because we’re inclined to believe he may well be a rapper-turned-actor, given his demonstrable ability to spit. There’s an easy route to take in the master-student relationship between Sher and Murad when they both intend to participate in Nas’ contest, but Akhtar knows better than to concede to familiar storytelling beats.

Then there’s the music producer Sky, played by Kalki Koechlin, the actress renowned for her unconventional choice of roles playing yet another groundbreaking character. Sky is e-introduced as a YouTube commenter who tells Gully Boy to step his game up and offers to make beats for him. Impressed by the composition sent to him, Murad asks Sher to accompany him to an in-person rendezvous with this online challenger.

Neither MC expected Sky to be a woman. She quickly relays her biography: she’s travelled from the USA where’s she’s studying at the Berklee College of Music in Boston. As an Indian seeking a culturally specific prospect for her assignment, she discovered Gully Boy and MC Sher over the internet and wants to complete her music production assignment with them.

The pair of rappers immediately acknowledge they have a knowledgeable and creative individual in their midst considering her education. The respect shown to her is very appreciable – it’s a much-needed reminder of the value in education (stemming from characters who live in the slums of India) when music students in wealthier Western nations often face ignominy for their selected degree.

Gully Boy: Conclusion

Some may preemptively dismiss Gully Boy as a rip-off of 8 Mile but there’s far more here than just another underdog hip-hop story. What sets this profound musical drama apart from 8 Mile is director Zoya Akhtar’s distinctive cultural lens. The themes associated with any rags-to-riches narrative are universally appealing but the inspiring essence of Akhtar’s drama is unquestionably born out of her thoughtful portrayal of slum life in Mumbai.

The filmmaker guides a quartet of phenomenal performances from Singh, Bhatt, Koechlin plus the hugely promising debutant Chaturvedi, who is alone worth the price of admission, and makes an even higher number of salient socio-political comments with them. There’s a satisfyingly sharp stab at colorism in a graffiti montage, and a smack in the face of whitesplainism in an early scene where a group of American tourists with a poverty fetish awkwardly take pictures of the slum houses.

One of them sports a Nas shirt, to which Murad says “Nice shirt” before offering the American offers an unwarranted explanation of who Nas is. To our delight, Murad cuts him off by rapping a few bars from the first verse of NY State of Mind. Hip-hop is an escape from life and a reflection of impoverished environments the same way in India as it is in the USA, and these gully boys are an example of its beautiful power.

What did you think of Gully Boy? Let us know in the comments below.

Gully Boy is out now in cinemas across the UK and USA as well as many international territories. For a full list of international releases, click here.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Musanna Ahmed is a freelance film critic writing for Film Inquiry, The Movie Waffler and The Upcoming. His taste in film knows no boundaries.