THE GRAND BIZARRE: On Sneezing & The Semiotics Of Fabric

Film critic, Ithaca College and University of St Andrews graduate,…

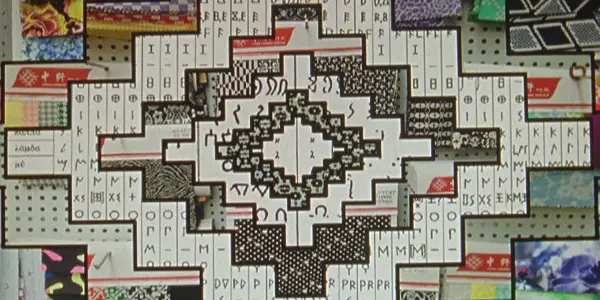

The Grand Bizarre evades classification. It’s a 60-minute musical, with most of the songs recorded by the film’s director and sole creative force, experimental artist Jodie Mack. It’s a documentary in which nearly every frame examines a fabric in production, in a market, traveling in a car, etc. The Grand Bizarre, named for the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul, is also a process film, comedy, experimental arthouse piece, video essay, making-of doc, ethnographic work, and stop-motion animation, a flurried travelogue of sound and color in a world of textures and textiles in motion.

Sometimes, The Grand Bizarre takes up a timelapse aesthetic, watching crates of textiles loaded onto barges as clouds pass impossibly fast overhead. Sometimes the footage is less edited. But its most thrilling presentation comes when Mack splices together still-life like stop-motion.

Raise the Red Flag

In one sequence of Mack’s film, bags reaming with reams of fabric zip themselves up and zip out of the room. The scene lacks the sophistication of clean, modern animation, resulting in a rough-hewn style that feels every bit as hand-crafted as the film’s fabric subjects. Though more laborious in replicating reality, stop-motion remains stylistically closer to the photographs of Eadweard Muybridge than any other modern method of filmmaking.

The Grand Bizarre is both the product of the experimental arthouse doc’s long metamorphosis, as well as a film that feels like it could have been made in the 1890s. Its contemporary subject accompanies a hundred-year-old formality. Mack’s focus on expressive color, for example, heavily elicits silent films — from Annabelle Serpentine Dance to the red flag in Battleship Potemkin — when color’s use in motion pictures was more about the dramatization of color than the colorization of drama.

Its presentation echoes the global appeal of silent films, too: The Grand Bizarre doesn’t have spoken words or narration, and the only text that appears on-screen is the symbols of the International Phonetic Alphabet — its universality is part of the point. And the soundtrack, divorced non-diegetically from the visual, recalls the old-school orchestral accompaniments of yesteryear.

You could show The Grand Bizarre to anyone, from any country on Earth, and the film would click. There are no barriers, linguistic or otherwise. And despite the epileptic frenzy of her montage, Mack has produced an almost soothing film, where the almost-antiquated filmic modality draws you in deeper instead of keeping you at arm’s length.

The film’s coda is a slower-paced montage of textile and map close-ups, set to the soundtrack of Mack’s photo workbench as the shutter clicks and she adjusts the fabrics. The film ends with Mack’s sneeze and a cut to black — another landmark silent film, from 1894, Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze, also ends with a sneeze and a cut to black.

Through a Bazaar, Bizarrely

Many sequences place the fabrics in the rearview mirror — be it on a motorcycle or a car — as though the things we make or consume become our identities. Lacking words and relying on her colorful cloth collages to communicate, Mack invents her own fibrous semiotics. The Grand Bizarre speaks with a material language of commodity, the expeditious animation accelerating through excesses of fabric, as Mack calls on her audience to confront the symbiotic relationship between artists and capitalism.

Her soundtrack embraces that partnership, too: One song begins with a synthesized birdcall symphony, suggesting humans’ ability to convert nature into art, then into commerce. The montages around these songs look pretty, but the soundtrack might as well be chanting, “Consume! Consume! Consume!” More damningly, it’s packed with jams — those who hate the film’s style should at least find it extremely danceable. The parodies of 4/4 pop time signatures cement Mack’s dread of what she calls (in a Film Comment interview) “fake and quirky global Muzak genericism.” She even sneaks in a bit of “Rhythm of the Night.”

Whether it’s pop music or textiles, The Grand Bizarre knows our society is built on the burial grounds of good, honest work that has long since been replaced by the most basic, culturally amorphous, easily consumable version of itself, be that Drake or Pier 1 Imports. (“There was going to be a big Drake element in the film that went away because I found his presence to be so overpowering,” she told MUBI’s Notebook.) Some of Mack’s images challenge the aesthetic functions of her fabrics — blankets hanging out of wheelbarrows or draped over a tree branch to dry, suggesting utilitarianism and a lack of fetishization. But we also know how much a nice pattern goes for online, and the kind of detached socialites who will buy those same blankets as sacrifices to the bougie bonfire of c*cktail party conversation.

No one is more aware of the immigrant allegory at the heart of these displaced fabrics than Mack. Originally, she said in an interview at Lincoln Center, “The way that I made the narrative in my own head was that there was a disaster and all of these textiles were displaced. And then they start their journey! And they start taking their boats, and they start riding on the trains.” This is perhaps why the film’s first image is one of burning fabric swatch towers.

Envisioning the sheer scale of the project, which took over five years to complete, you start to think about how many fabrics Mack must’ve used in total to make her stop-motion playground, and how that number dwarfs in comparison to the surplus of fabrics we use every day.

It Ain’t Much, But It’s Capitalism

Maybe that interrogation of consumerism is what’s so striking about the film’s throwback style. Film began life as an invention, then quickly turned into a corporatized venture. Edison’s Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze, after all, wasn’t just a cutesy joke film to show in nickelodeons — it was an advertisement reel for Thomas Edison to show investors, and it’s now recognized as the oldest surviving copyrighted film.

Part of the medium’s languid embrace of sound and color is that silent, black-and-white films were plenty profitable without the costly installation of more advanced recording and projection technology. As with textiles, the line between functionality and aesthetics is always blurred. Film and fabric are conglomerate to art, to a shared semiotics of color, pattern, and perceived culture.

Images of textile factories and hundreds of fabrics that could be the products of either working hands or machines aren’t different from the more ambiguous machine of film production. Where once teams of dozens of women were required to hand-color film, one editor can now do the same work in an hour in Adobe After Effects. At the same time, The Grand Bizarre seems to refute its own view of the conformity of labor — the film is the indisputable vision of Mack and Mack alone.

And all of her art — most of which is close-up textile work like The Grand Bizarre’s concluding minutes — forces its audience to confront the materiality of the medium they’re watching. You can feel in every frame the method and labor by which The Grand Bizarre represents art at its most autocratic. It’s there in the imperfect stop-motion, in the spontaneous soundtrack, in the grain of the 16mm film, and yes, especially in the sneeze.

What do you think of Jodie Mack’s The Grand Bizarre? Let me know in the comments below.

The Grand Bizarre is streaming worldwide on MUBI as of April 9, 2020.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Film critic, Ithaca College and University of St Andrews graduate, head of the "Paddington 2" fan club.