Queerly Ever After #1: GIRL STROKE BOY (1971)

Amanda Jane Stern is an actress, writer, and director from…

The 1971 British farce Girl Stroke Boy has the distinction of being the earliest, (that I’ve found so far), non-coded, film where an LGBT couple ends up together. It is not what anyone would call a great movie – never have I seen a film with the boom mic present in so many shots; in one scene towards the beginning of the film, the boom can be seen in the top of the frame, finally the boom moves out of frame only to reappear, in the same shot, in the bottom of the frame.

However, it is a fascinating piece of cinematic history for its positive portrayal of a trans woman-of-color and her romance with her cis-gendered, white boyfriend. A portrayal that, in many ways, is still more progressive than a lot of current cinematic depictions of trans people.

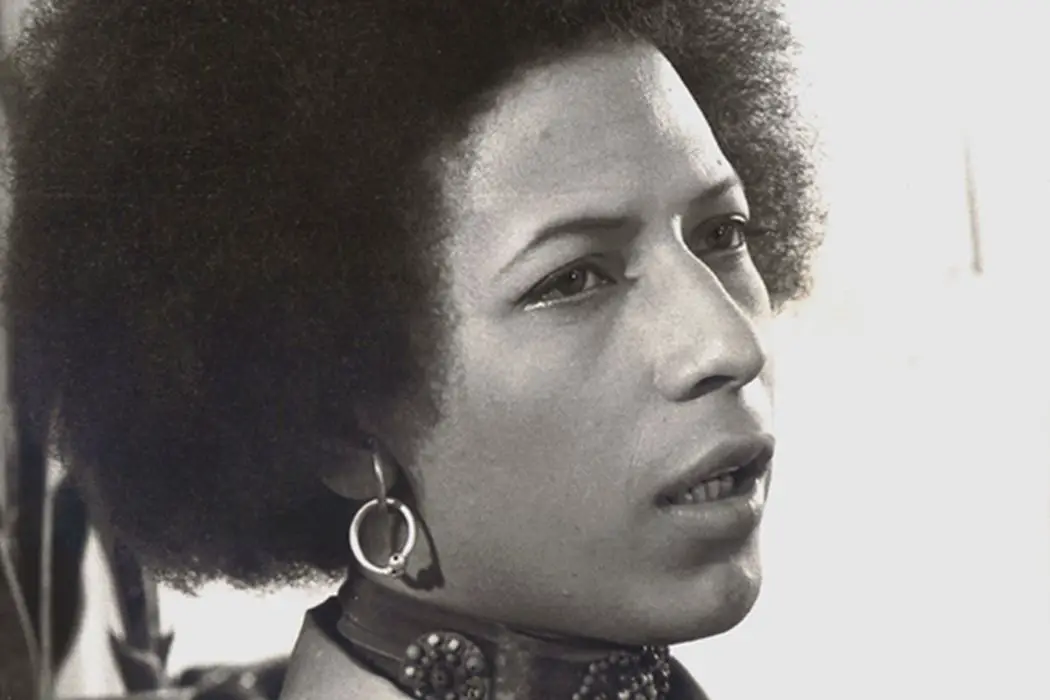

The film, written by Caryl Brahms and Ned Sherrin and directed by Bob Kellett and based on the play Girlfriend by David Percival, tells the story of a young man named Laurie (Clive Francis) who brings his girlfriend, Jo (Peter Straker), home to meet his upper-middle class parents. What is originally set up as a sort of British Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner is thrown for a loop when Laurie and Jo arrive home and Laurie’s mother, Lettice (Joan Greenwood), is immediately struck by Jo’s masculine appearance. Lettice proceeds to go to great lengths to determine whether Jo is a woman or a man.

The idea of using a character’s gender identity as a big mystery that propels a story is dubious, one wrong step and you can seem to imply that trans people are inherently deceitful and hiding a big bad secret. Girl Stroke Boy never makes that mistake because the script always firmly supports Jo. She is never the butt of the joke, but Lettice and her closed-minded attitude are.

Meet the Parents

Before Laurie and Jo arrive home we are introduced to Laurie’s parents: religious school teacher George Mason (Michael Hordern), and best-selling author Lettice Mason. It quickly becomes clear that both parents have very different views on Laurie bringing home a girlfriend. George is thrilled that Laurie is bringing a young woman home, he never knew his son to be interested in girls before, (we’ll come back to that later) and he’s looking forward to meeting the woman who’s caught his son’s eye. Lettice on the other hand, refuses to refer to Jo as her son’s girlfriend, she merely refers to her as his friend. While Lettice considers herself a liberal, progressive woman, she cannot fathom the idea that her son is serious about a black woman, even going as far as to say:

Of course he can’t be serious, But we can’t afford to be narrow-minded George. The message of my work is love. The message of my life is love. I can love the beautiful black daughter of a, thank god, West Indian high commissioner just as well as I can love a shop-girl. More probably, because the relationship is less likely to be permanent.

As open-minded as Lettice believes herself to be, she is, in modern parlance, fake-woke. When Laurie and Jo arrive home the chasm between George and Lettice’s views only grows. George is immediately taken by Jo, he thinks she seems wonderful. Lettice is disdainful, not only is she not happy that her son’s girlfriend is black, but now, she doesn’t think her son’s girlfriend is a girl.

For what it’s worth, Laurie did not expect his overbearing mother to be accepting of Jo – both he and Jo know that it’s going to be an uphill battle. In George, Jo immediately senses an ally and pulls him aside to ask him to help out with Lettice. George is happy to oblige the young couple. He proceeds to spend the movie fighting against Lettice and her schemes to “out” Jo.

While Laurie and Jo go upstairs to unpack their bags, Lettice comments to George that she doesn’t think Jo is a woman. She then tries to convince George to ask Jo about her gender to which George responds, “I like Jo a great deal. I think she’s a good person and she is good to Laurie…That is all I’m prepared to say.” he goes on to tell her that Laurie has the right to be with whomever he wants and Lettice just has to accept that.

As the two couples sit down to dinner, Lettice zones in on Jo, asking her questions about her name (“it’s an odd name for a girl”) and her job (stewardess). At one point she asks Jo how it is being a steward and Laurie snaps back “stewardess.” As the night wears on, so do Lettice’s snide remarks. When Jo uses the bathroom, Lettice goes in after her to check whether the toilet seat is up or down. When she sees that Jo is wearing similar pyjamas to Laurie instead of a nightgown, she inquires whether Jo has ever worn a dress. George throughout the night tries to convince Lettice to give it up and just go to bed.

Mother Doesn’t Know Best

The next morning, over breakfast, Laurie mentions that he’s thinking of having his childhood best friend, Arthur, over to meet Jo. Lettice intervenes asking won’t Arthur be jealous, implying here that Arthur is gay and will be jealous that Laurie chose to date Jo instead of him. This goes back to the earlier remark from George about Laurie not seeming interested in girls before, and the incorrect notion that a cis-man dating a trans-woman makes the man gay. Laurie thinks his mother is being foolish, his interest in Jo and lack of interest in the girls he grew up with is not because Jo is trans, but because Jo is interesting and exciting and the small-town girls with whom he grew up were dull. Seeing that his Mom will not drop this topic though, Laurie decides that he and Jo will go meet Arthur at the local pub instead of have him come over.

While Jo and Laurie are out Lettice resolves to get to the bottom of this supposed mystery. As she continues to badger George to help her he responds with,

Laurie says she’s a woman, she says she’s a woman. With such evidence, I am prepared to take her femininity on trust…Sooner or later you have to take somebody at her word and I think she’s a girl.

Of course, Lettice refuses to let it go and in a true move of complete disregard for boundaries, she calls up the operator to ask for Jo’s parents phone number. When she does receive the number she tries to convince George to call them and ask if they have a daughter. She figures since George has been sure that Jo is a woman, it should be no issue for him to clear it up with her parents.

This is where something really interesting happens. Lettice calls up Jo’s parents and forces George onto the phone with them. Despite the fact that George has just spent the entirety of the film referring to Jo with female pronouns, he refuses to use gendered terms while speaking to her father, instead he only refers to her as Jo. This infuriates Lettice of course, who continues to prod him. George waits until almost the end of the conversation to slip into the conversation that he likes their daughter immensely, Jo’s parents respond by saying they are looking forward to meeting his daughter Laurie, as well. Jo’s parents do not deny that Jo is their daughter, they just assumed that she was with a girlfriend based on Laurie’s name.

It has to be asked why, if George firmly believes Jo is a woman, was he so hesitant to ask her parents that. Was it because Lettice’s words were getting to him and he was beginning to question Jo’s gender? Or, does he inherently understand that Jo is trans and while he accepts her, he does not know if she is out to her parents and does not want to potentially put her in a situation where he outs her and her parents don’t accept her. Lettice cannot understand why it was so hard for him to ask her parents, even he can’t completely understand what stopped him from using female pronouns while on the phone but he intrinsically knew to protect Jo and he has had more than enough of Lettice’s behavior. He snaps at her, saying,

Lettice, I’m a liberal coward. But everyone has a right to live his own life, make his own decisions. It’s a right that I will defend for my son even against my wife.

He goes on to say he does not care whether Jo was born biologically male or female, all he cares about is that his son has found someone he loves who loves him back and clearly makes him happy. Lettice cannot accept this and threatens to leave, but this is a fight George will not let her win. This is why, for all its flaws, the movie works because it firmly understands that Lettice is in the wrong.

Wrapped up with a Bow

Laurie and Jo return home and the movie starts to prepare its ending. This is probably where the movie falls apart most. It knows it can’t keep dragging on, but the script also knows that Lettice is so dead-set in her views there’s no way of her accepting that she was wrong. In trying to neatly end the film, it becomes rather clumsy. Lettice again tries to confront Laurie about Jo, Laurie responds, “Mother dear, doesn’t it ever occur to you that I might know everything that she is, and isn’t by now?” He then decides to tell his parents that he and Jo have actually gotten married, in a church, the day before they came to visit. No, they have not really gotten married, but Laurie does this to create a charade that his mother will accept. And she does, immediately. George understands what Laurie is doing and goes along with it, comprehending that the only way Lettice will drop this subject and accept Jo is by allowing her to live in a bubble of her own delusion.

In the end does Lettice really learn from her mistakes? No. Were this movie any genre other than an all-out farce, perhaps the film would have ended with George, Jo and Laurie cutting Lettice out of their lives until she can truly accept Jo. As a farce, the film wanted to wrap up neatly, and it did, albeit clumsily. All that being said, Jo and Laurie get their happily-ever-after, and isn’t that really what matters?

Girl Stroke Boy came out August 12, 1971 in the U.K. It was never theatrically released in the U.S. It is currently available to watch on Amazon Prime UK.

How do you think Jo compares to representations of trans people in cinema today? Do you think there as been progress made here? Let us know in the comments!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Amanda Jane Stern is an actress, writer, and director from New York City. She received her BA in Film, Television & Interactive Media and Theater Arts from Brandeis University. She loves regaling whomever will listen with her endless lists of fun facts and knowledge of film history. Follow her on twitter and instagram @amandajanestern