GANJA & HESS: Beyond The B-Movie Aesthetic

Data analyst living in Manchester. Writes for Film Inquiry, The…

A story doesn’t have to make sense or even be any good. Ganja & Hess is neither coherent in its storytelling or particularly interesting when some of it sticks together. Yet when Dr. Hess Green wanders the fields around George Meda’s estate, having seen Meda shoot himself and having licked “da sweet blood” from the gun wound – at that moment, I felt the buzzing in my ears and sizzle in my chest that great films have the power to ignite. This sensory reaction to the alchemy taking place on screen has nothing to do with the power of storytelling, and everything to do with the energy created when certain sounds and images react with one another.

Gunn Wound

Ganja & Hess was chopped up, re-cut and re-titled because of disappointing box office figures after a limited first release in the US, despite making a show at Cannes Critics Week in 1973. Bill Gunn – director, writer, and actor – wasn’t disappointed, rather his producers were, thinking they were about to cash in on a black vampire picture when similar films were earning good money.

But Gunn made the film he wanted to make, and we are lucky that his original cut was taken in by the Museum of Modern Art and preserved for our pleasure. The supposedly inferior re-cuts were called Blood Couple, Black Evil, Black Vampire, Vampires of Harlem. Its original title, Ganja & Hess, suggests Gunn wasn’t interested in making the film that he had promised his producers. The film is a collage of images and sounds. For the most part, it can be mesmerizing, but it demands attention.

The Addiction

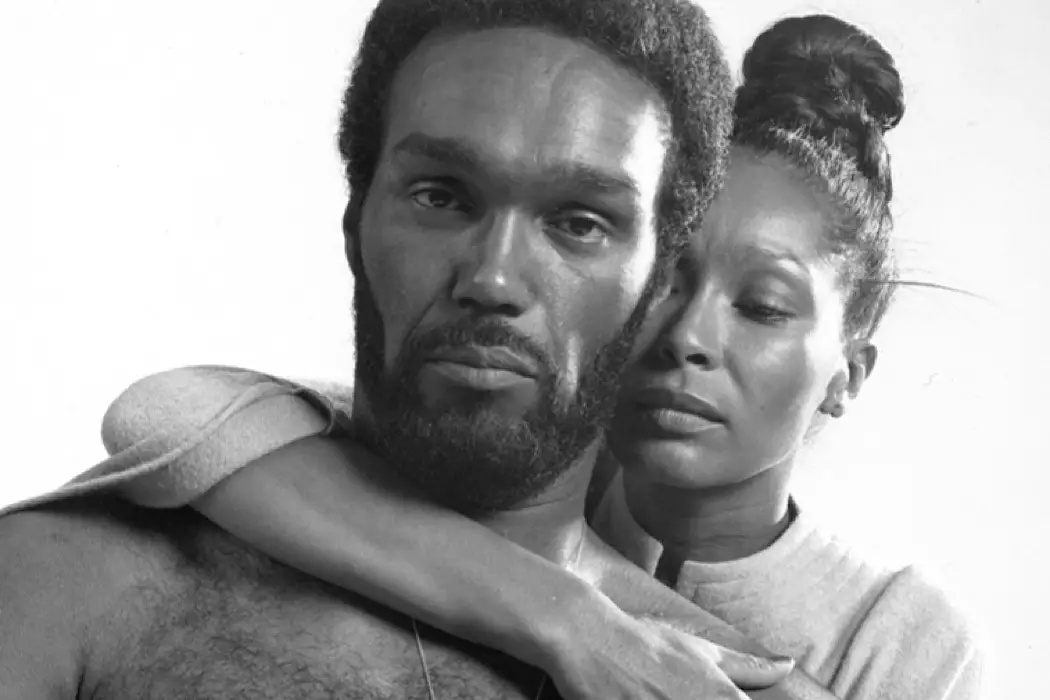

Under the guise of a vampire movie, Gunn intended to make a film about addiction. Ganja Meda, having been turned into a vampire by Dr. Hess Green, lays in front of the fire in his arms and says, “Are you always cold?” The doctor replies, “Grown used to it.” Sadness takes over the two characters once they have settled into their new (everlasting) lives together.

There is wonderful documentary-like footage of a church congregation, led by a charismatic preacher. It becomes clear that he is a friend of Dr. Hess Green, but his inclusion in the film is somewhat perplexing. This is until the end of the film when there is a moment of salvation for the doctor. At first, these scenes are inexplicable, but they become the emotional end to a film that was seemingly only interested in intellectualizing the vampire myth.

Conclusion

The film making is far from flawless, but what Ganja & Hess really projects is the sense that it came from a person who wanted the work to reflect himself. It is a personal film, its creator having put his art and intellect on the line. Much of the dialogue is played for how it sounds, sometimes even buried under great sound abstractions that deepen the otherwise absent feeling of dread usually expected in horror films. But when the actors do get a chance to take on a monologue, there is a sudden expansion of the world Gunn has created, and the poetic, philosophical riffs surpass the B-movie aesthetics to create an art movie with real blood on its lips.

Have you seen the film? What are your thoughts? Let us know in the comments!

Watch Ganja & Hess

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Data analyst living in Manchester. Writes for Film Inquiry, The State Of The Arts, Vague Visages.