FRANK VS. GOD: An Important Farce That Gives Atheists A Voice

Alex Arabian is a freelance film journalist and filmmaker. His…

Frank Vs. God likely missed almost everyone’s radar. Apart from Henry Ian Cusick, who played the Emmy-award nominated character, Desmond, on the hit series, LOST, the film didn’t have much star appeal. Despite winning several awards at smaller film festivals in 2014, it only recently secured distribution via streaming with Amazon.

It marks television editor Stewart Schill’s sophomore writing and directorial effort in his nearly-30-year career. However, cinephiles may notice that a descendent of acting royalty is billed in the cast; Ever Carradine, granddaughter of the iconic character actor, John, daughter of Robert, and niece of Keith and the late and great David Carradine, shines alongside Cusick. It is wonderful to see another Carradine on the silver screen again.

The very premise alone that the title, Frank Vs. God, overtly implies could be an apt setup for a a Lifetime film about a man who loses his faith and then miraculously finds god. Had this film had a wider release, a portion of the more devout viewers expecting something religiously propagandistic along the lines of Heaven Is For Real would be more likely to head to their nearest place of worship and advocate for an immediate worldwide ban of Frank Vs. God. Refreshingly, Schill provides an empowering perspective of a historically disenfranchised group: people who don’t believe in god. Atheists. Furthermore, he sheds a necessary light, pardon the heretical wording, on the hypocrisy, corruption, destruction, and abuse of power that possesses the institution of religion.

However logical of an argument Frank Vs. God makes against the validity of god, it doesn’t fall victim to becoming too preachy because it provides a rather empathetic viewpoint of religion through the group of religious leaders taking the stand for god in court. It underscores the good intentions of religious corporate entities, ideologically, while giving their actions a harsh but fair critique.

Blasphemous And Clever Fun

All David Frank (Cusick) wants is accountability for the loss of his house and beloved dog, Brutus, in a tornado. Deemed an “act of god” by his insurance company, and therefore not financially covered, Frank hits a new low. Already having recently lost a wife in a car accident, Frank has nothing left to lose, so he decides to confront the big man upstairs in a court of law. Frank Vs. God starts out somewhat rocky and struggles to find its footing, but by the end of the first act, the film’s tone hits a common frequency thanks to Jonathan Beard’s cunning and cheekily foretelling score; one can think of it as a pleasant ode to Rachel Portman’s fanciful score for Benny & Joon.

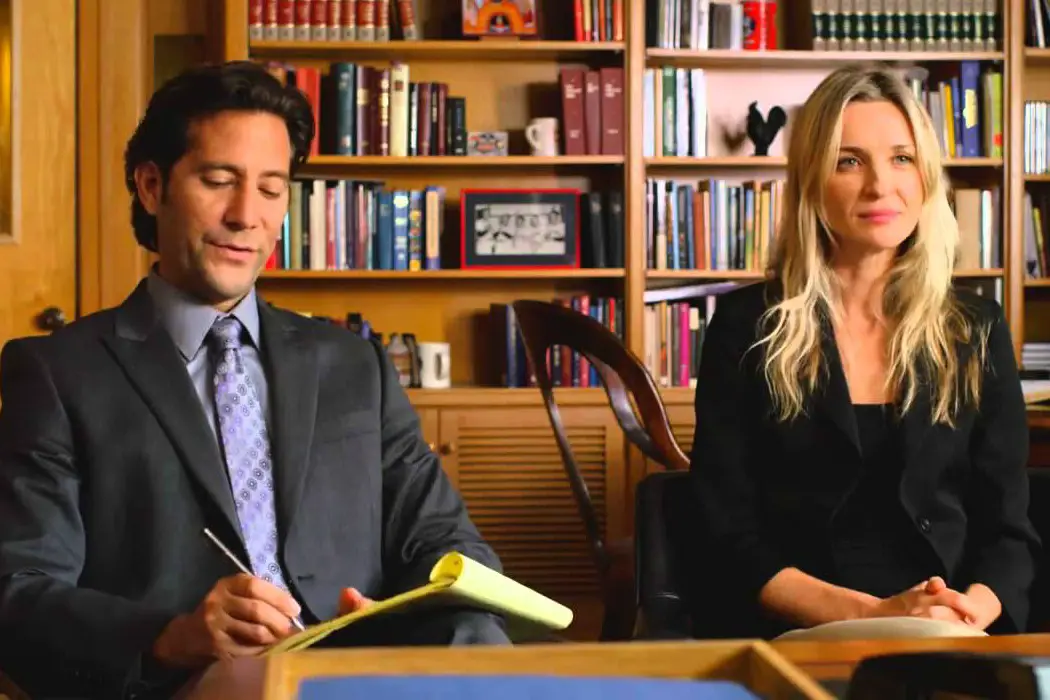

Schill does his fair share of research, garnering a wide enough overview of the law to indirectly make glaringly inarguable loopholes in the argument for the existence of god through disproving the validity of the term “act of god.” Cusick, having proved himself to be more than adept at playing unhinged characters in the past, immerses himself into the courtroom. Carradine as his legal counterpart defending god offsets Cusick’s intensity with a somber, sulking, and inspirational performance as a person struggling with demons of her own.

Low Budget? No Problem

There are certain scenes in Frank Vs. God that ride the fence of quality, bordering Hallmark Channel territory. The only critique about Schill’s second film that is worth noting is that, ironically, the editor gets in the way of himself. The directing is entirely adequate, particularly given the film is character and actor driven. However, Schill, known for editing episodes of Charmed, Dexter, American Horror Story, and American Crime Story, hasn’t been able to escape the jolting transitions that cable television inherently begets. Television is built around keeping the viewer in constant suspense, waiting for the commercial break to end, the next episode to arrive, the next season to be released. In that capacity, Schill is still in television mode.

However, the choppy editing can’t slow down the film once it gains steam. The angelic lighting and the fantastical cinematography of Stephen Campbell provide for a well-executed contrast to the complexity and controversial nature of the subject matter. At its heart, it is a film about human redemption through love. At its brain, it is a film about the infinite fundamental paradox of god. Rays of poignancy shine through at times, and elements of grittiness can be seen through some of the more raw courtroom speeches and media coverage of the event.

Schill makes sure to keep Frank Vs. God lighthearted enough, adding a slapstick backstory of the trial’s judge, who’s hellbent on using this case to elevate his own fame and strengthen his chances of becoming a congressman. In the process, by adding to the satirical tone, it also sheds light on the absurdity of the blurred lines between church and state. Separation of church and state has been a constitutional pillar of the First Amendment, yet religion and government have become increasingly codependent in America.

Thought-Provoking For All Viewpoints

When an audience is engaged in compelling subject matter that is expressed by emotionally intuitive actors through dialogue that is realistically constructed, budget is seldom an issue. Frank Vs. God is no exception; it is a thoroughly watchable, intelligent, slightly schmaltzy albeit sporadically profound satire about religious differences.

There is a rather sizable population that doesn’t believe in god, and an even larger one that doesn’t adhere to a particular religion. These groups are the minority, but likely vaster in volume than any poll would suggest due to the societal consequences of outing oneself as either atheist or agnostic. They will find comfort in viewing this film, which takes this demographic seriously. The Jewish rabbi, the Catholic bishop and priest, the preachers of various protestant sects, the Buddhist monk, the Jehovah’s Witness, the Rastafarian minister, etc. are all represented as human beings.

Thankfully, though likely still not enough to atone for its blasphemy in the eyes of certain religious extremists, Frank Vs. God does not villainize these people, but rather simply vocalizes what the word god means to them. The idea of god is not always as mystical to many who believe as is commonly perceived. Many devout religious and spiritual people interpret god as a verb, not a noun; an action, like loving, caring, or helping others.

In Conclusion

Frank Vs. God brings up many questions, makes solid arguments for and against the effectiveness of religion and the existence of god, but, like reality, this fairytale doesn’t offer any life-changing answers. Who could justify all of the destruction and countless innocent slaughter that religion has caused over the last 5,000 years and continues to cause by the thousands each day? Who could ever truly prove or disprove the existence of a higher being? Instead of trying to do so, Frank Vs. God offers a more humanistic perspective on the nuances and sensitivity of interpersonal connection in an innately cruel and harsh world.

Are you excited for Schill’s next directorial effort? What was your favorite moment in Frank Vs. God? Tell us in the comments below!

Frank Vs. God was released on certain digital streaming platforms on March 7, 2017, and became available on Amazon and iTunes on June 12, 2017.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Alex Arabian is a freelance film journalist and filmmaker. His work has been featured in the San Francisco Examiner, The Playlist, Awards Circuit, and Pop Matters. His favorite film is Edward Scissorhands. Check out more of his work on makingacinephile.com!