Over at our official Facebook page, we are currently posting daily film recommendations, with each week being a different theme. This is a collection of those recommendations! This week’s theme is focused on women-directed films of the 1970’s.

The 1970’s are commonly referred to as the greatest decade in cinematic history, due to the combination of various cinematic movements intersecting at the same time. The rise of arthouse, brought on by the French New Wave was inspiring American filmmakers to change their ways, mixed with the classical Hollywood system that had ruled since the 1920’s had slowly died out due to better technology and an added level of cynicism in the American public.

Due to the studios not knowing what to do, they threw money at everything, giving creative young directors the freedom to experiment and produce some of the best-known films of all time – Easy Rider, The Godfather and more. In between these films, the rise of the women-directed films happened, thanks to a less structured filmmaking system and changes in gender roles in society. Here’s just some of the great films directed by women from that period.

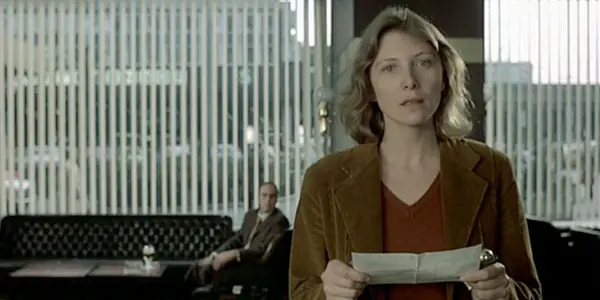

1. Les Rendez-Vous d’Anna (1978, Chantal Akerman)

Chantal Akerman’s deeply personal character study is just one of Akerman’s great films of the 1970’s. Chantal Akerman is one of the most important woman filmmakers of all time, an independent Belgian filmmaker who made shorts, feature films, documentaries and more in her diverse career. After finding huge critical success from Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles in 1975 after a string of successful short films, Akerman made quite a few films from the 70’s up until her death in 2015. Les Rendez-Vous d’Anna was one of Akerman’s most personal movies, a pseudo-biographical film which deals with personal sacrifice for the sake of chasing your creative dreams and the consequences of such actions.

Anna (Aurore Clement), a successful filmmaker, is currently on the promotional tour for her latest movie, which has her visiting various European cities, which increases her growing detachment from the world around her. As Anna visits each city, she meets different people in an assortment of encounters which each highlight different aspects of Anna’s personality. The film has an autobiographical feel as both Anna and Chantal Akerman are both Belgian filmmakers who have both found success in arthouse cinema, which makes the emotion in the film feel genuine.

Aurore Clement does a terrific job as Anna, as Akerman’s filmmaking style demands actors to really communicate their feelings through action, rather than dialogue. One of the trademarks of Akerman’s films is her minimalistic dialogue, characters with quiet reservation who merely shelter themselves from an outside world that they feel separated from. The film is a character study, a protracted jigsaw where the audience slowly starts to piece together the character of Anna as she has a one-night-stand, sees her ex-partner and remains disconnected to all the newcomers in her life.

If you’re a fan of Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation, this is the precursor to that film, a film which really gets into the emotional state of feeling alone in a foreign environment and merely trying to find some connection to those around you.

2. Harlan County USA (1976, Barbara Kopple)

Influential documentary filmmaker Barbara Kopple’s debut feature film, Harlan County USA, is one to be remembered. Since its debut, the film has been added for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” and also ranked 24th on Sight and Sound’s “Greatest Documentaries of All Time” list from 2014.

Harlan County USA is a great example of the limitless stories that can come from documentary filmmaking. Kopple had originally planned the film to be about the union ‘Miners For Democracy’ attempt to unseat the current president of the United Mine Workers of America union, Tony Boyle. Once filming had begun, Kopple started to hear about the Brookside Mine in Harlan County, Kentucky starting to strike, she shifted the focus of her film.

The strike was a dire 13-month affair, which finally ended in tragedy. Using no narration, allowing the images to speak for themselves, Kopple paints a tragic picture of the lives of the miners affected, where she spent several years with the different families, some who were living in states of poverty due to the poor working conditions.

The frequently violent scuffles between authority figures and the increasingly desperate striking miners is some quite engaging footage, a raw, unedited depiction of the struggles that many have had to go through just to get fair working conditions. At one point in the film, Kopple and her cameramen are attacked themselves, all depicted on-screen in a very famous scene. Kopple’s unflinching look at the struggle between greedy upper-class corporate figures and the rebelling lower class is one of the definitive documentaries of the 1970’s, a great example of the pure filmmaking that can be captured by smart documentary makers, much like Kopple.

3. A New Leaf (1971, Elaine May)

Elaine May is a comedienne whose long and still continuing career is filled with quite a few influential and important moments. She initially caught fame from being the female half of the comedic duo Nicholas and May, with Nicholas being Mike Nichols, who would go onto be a successful comedic director. Their sarcastic style of humour, which critiqued the usual gender stereotypes in comedy, was largely influential to all comedy duos that followed, especially those that were gender mixed. After they split up, May went into films as well, directing A New Leaf as her feature debut, a snarky rom-com which avoids falling into the standard rom-com tropes.

Henry Graham (Walter Matthau) is a lazy playboy who has coasted all of his life living off his parent’s large inheritance they left him. Now Graham is screwed because the money has run out but Graham refuses to try and get a job. Instead he plans on marrying a rich girl, killing her and inheriting her wealth. He meets Henrietta Lowell (Elaine May), but his plan starts to come apart when he starts falling in love with her.

Despite immediate critical acclaim and several award nominations, the film did poorly at the box office and was quickly forgotten by mainstream audiences. Elaine May’s last directed feature film was the infamous Ishtar, the critical and commercial bomb which became the talking point when referring to any form of other movie bomb.

Due to these two commercial failures, the mainstream reputation of Elaine May was ruined and, sadly, many modern audiences are unaware of her comedic talent. A New Leaf is a terrific comedy, a female version of Woody Allen’s better films, a darker turn on the typical predictable rom-com.

4. Seven Beauties (1975, Lina Wertmuller)

Lina Wertmuller is a very controversial Italian female director, who, throughout her career, has pushed the cinematic boundaries when it comes mixing different sensitive subjects together, such as gender and political debates, sex and comedy and much more. She is the first woman to receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Director (for this film, Seven Beauties). She received her start when meeting Federico Fellini through a mutual friend and he offered her a part as assistant director on his hit film 8 1/2. She made several features, but achieved international acclaim from her streak of films in the 1970’s, with Seven Beauties being the one to bring her name into moviegoers’ attention.

Pasqualino Frafuso (Giancarlo Giannini, who would become a regular of Wertmuller’s) is a regular everyday Italian man, who deserts the army during World War II. Eventually captured by the Germans and sent to a concentration camp, the film explores Pasqualino’s lengthy past which has lead him to this moment. His past includes start as a petty thief taking care of his seven sisters, his eventual murder of one of his sister’s lovers, his imprisonment in a mental asylum and his eventual decision to join the army in order to avoid jail-time. As he regularly tortured in the concentration camp and treated horribly, he decides to plan his escape by seducing a female German officer.

Seven Beauties is a harrowing depiction of masculinity and the uncomfortable internal decisions that people must make sometimes in order to do the right thing. Despite his regular, normal personality, Pasqualino is a character who, due to his upbringing in a female-dominated environment, mixed with the demands of a very masculine Italian neighbourhood, has always stuck to a dated, somewhat flimsy code of honour, which as the film shows, always leads him to trouble. His arc of having to sacrifice his code when detained in the concentration camp in order to escape generates the film’s great emotional impact.

Wertmuller’s strong direction, effortlessly moving between the brutal depictions of concentration camps, the sexual nature of Pasqualino and sometimes into light comedic territory, is done without any abrupt shifts in tone.

5. The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (1975, Volker Schlondroff and Margarethe Von Trotta)

Directed by the husband and wife team of Volker Schlondroff and Margarethe Von Trotta, The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum is a merciless attack on sensationalist journalism and the deep effects of tabloid exhibition. It was made in West Germany during a time of troublesome political controversy and a nimble period in history where journalists where frequently crossing moral boundaries for the sake of getting famous or fabricating stories to sell papers. The film is based on the novel of the same name by Heinrich Böll, who experienced similar experiences to that of the titular character, Katharina Blum.

Katharina Blum (Angela Winkler) is an innocent housekeeper who has a chance encounter with the mysterious Ludwig (Jürgen Prochnow) at a party. After spending the night with him, he escapes and Blum is immediately arrested. Ludwig is revealed to be a radical terrorist and bank robber and in a desperate attempt to track him down, the police relentlessly harass Blum. Moreover, Blum is put in the centre of a media storm, with the various German publications condemning Blum, which starts to test the limits of sanity and her physical health. Nearly snapping, Blum decides to fight back against the journalists that have made her life hell.

The film’s heavy criticism of the mainstream media’s vindictive nature towards their innocent targets is one issue still relevant today, one which has been heightened due to the easier avenues of communication brought by the advent of social media. Whilst co-directed by the married pair, this was the directorial debut of director Margarethe Von Trotta, who, after this film, started to direct on her own, making several feature films still to this day (Her latest film, Die Abhandene Welt, came out only last year). Whilst the ending may seem jarring to some, the film takes some interesting narrative twists and turns, a gritty political drama which was luckily revived by the Criterion Collection several years ago.

6. The Night Porter (1974, Liliana Cavani)

The Night Porter is Liliana Cavani’s best known film, a highly controversial exploration of sexual relationships, dealing with the past and the repetitive nature in which humans act in. The film uses the framing of a Nazisploitation (Nazi exploitation) film in order for Cavani to tell her story, a decision which divided many critics at the time. Some critics, such as Roger Ebert, saw Cavani’s use of World War II and Nazis are exploitive in a offending nature, giving dimensions to the Nazi characters who were usually relegated to two-dimensional villains in most mainstream entertainment.

Whilst opinions are subjective, these criticisms seem to be viewing the film on a surface level – merely witnessing the combination of a complication sexual relationship mixed with the contextually evil Nazis makes for complicated viewing – especially when viewed through the filter of exploitation, which adds a dimension of heightened male gaze and enjoyable engagement into the mix, which is a dramatic shift in what audiences are used to when it comes to depictions of Nazis on-screen.

In 1957, Lucia (Charlotte Rampling) a former teenage Nazi concentration camp inmate, accidentally meets her former tormentor Max (Dirk Bogarde) in a Vienna hotel where Max now works as the night porter. The former SS Officer engaged in a sadomasochistic relationship with Lucia during World War II, where she suffered mentally and physically at the hands of the Nazis. Striking up a conversation, the pair reignite their previous relationship, but when Max’s old Nazi friends find out about this, they decide to try and put an end to it once and for all.

The film is a study of insanity without condemning the main characters who are both suffering. Charlotte Rampling is always a terrific actor to watch, whose crazily diverse career has seen her go from arthouse (The Damned), to horror (Amicus’ Asylum), exploitation (this film), mainstream trash (StreetDance 3D) and much more, and she just earned another Oscar nomination for her lead role in 45 Years (one nomination which is deserved).

Whilst the film is quite disturbing and the frequent Nazi imagery may put off some viewers, Cavani’s brutal study of two damaged people is well-crafted film which sheds its exploitation trappings and becomes a much deeper film than one may expect.

7. Wanda (1970, Barbara Loden)

Are there any other 1970’s films directed by women that you can recommend?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.