Femme Filmmakers Festival 2022: Competition Shorts, Days 4–6

Film critic, Ithaca College and University of St Andrews graduate,…

Femme Filmmakers Festival 2022 is the seventh year for the event, run by Filmotomy and partnering with MUBI, In Their Own League, and InSession Film. The online festival runs for 10 days, with a showcase selection and a host of feature films. Its competition selection comprises 20 short films this year — all are directed by women. These films show for days one through nine, and the 2022 festival ran from Sept. 23 to Oct. 2. Days one through three brought a series of seven strong, impressive competition shorts; these shorts were programmed on days four through six.

The six shorts on these days are dramas — about abortions, about skateboarding, about dead things and resurrections. They run the gamut from a tender portrait of a Haitian family to a father’s experiences after death to a music video sculpted from clay. Some of the films are available to watch online.

Frimas (Marianne Farley)

On day two of the festival, Polished provided a measured, subtle, vérité look at abortions in the U.S. Now, on day four, Frimas looks at abortions in Canada — this time, with a dystopian twist.

As though real-life abortions aren’t frightening and traumatic enough, the one in Frimas is conducted in the back of an ice-cold meat truck as it drives down a bumpy highway. It’s a hell of a Stanislavski test for actress Karine Gonthier-Hyndman, who somehow finds a way to ground the desperation, pain, trauma, guilt, and ultimately, lack of relief on her character, Kara’s, face.

At the outset of the 19-minute French-language short, Kara needs an abortion — though in this all-too-possible dystopian Canada, the procedure is illegal, prohibited strictly by law, and the meat truck is the only choice she has. The doctor (Chantal Baril) and the driver (Kent McQuaid) empathize with her plight, but they’re sticking their necks out for her. And that’s never more clear than when they’re pulled over by the police, leading to a tense-as-hell sequence where the cops search the truck and the hanging pig carcasses in its back while the doctor and Kara try to stay out of sight.

Many of cinematographer Benoit Beaulieu’s shots, from the smooth, crisp top-down drone photography at the beginning through to the devastating close-ups on Kara at the end, are remarkable and inventive, capitalizing on a bitter Canadian winter and the stark gray and white of a snowy highway. (You can’t set a dystopian story during the summertime, now can you?) And the editing, from Mathieu Bélanger, leans into the difficult nature of the material, threatening every scene to find new ways of taking your breath away.

Writer-director Marianne Farley — who also wrote and directed the Oscar-nominated 2017 short Marguerite — finds in the situation a fascinating metaphor for abortion itself — just as Polished echoes its abortive procedure with the protagonist getting her nail polish scraped off and a fresh coat applied and the ways in which women are destroyed and renewed, Frimas asks you to consider the ways in which women are controlled. Hidden among pig carcasses, Kara is analogized as livestock, a thing to be bought and sold at the whims of a patriarchal system that enacts violence against women as a means of control.

Abortions in Canada, unlike in the U.S., are legal all around, or at least, they are for now. But clinics are far more common in cities, especially those along the U.S./Canada border than they are in rural parts of the country. For viewers in the U.S. or in other countries where abortion isn’t a protected right — including the 24 countries in which it is illegal altogether — Frimas is a familiar horror.

Frimas won the festival’s Dog Tooth (Film Third Prize). Frimas is available to rent on Apple TV+.

Scratched: Lee Ralph (Madeleine Chapman)

Lee Ralph, in his Bob Marley slacks, black shoes, black hoodie, and black beanie, which covers some of his dreads, has a rusty laugh and a pirate smile. He’s a skateboarding legend, especially in his home country, New Zealand — or Aotearoa, as the Māori know it as.

In the 1980s, Lee Ralph was on track to be one of the best. He began skating at a young age, helped by his mentor, Gregor Rankine, who’d broken his leg skating in America and came back to teach Lee everything he knows. And like Rankine, Lee went to the states as a teenager. He finished in the top six in his first contest — no newbies ever make it into the top eight. Soon, Lee got a sponsorship deal with Vision Street Wear, was skating against Tony Hawk, and was making a name for himself. How did he maintain his focus and stay on top? “The time they’re spending doing that [drugs and drinking], I’m hammering at the ramp,” Lee says. “All day. Just getting better and better and better.”

Scratched: Lee Ralph, a 12-minute documentary, is part of a longer YouTube series produced by The Spinoff that shines a spotlight on Aotearoa’s forgotten sporting icons. Directed by Madeleine Chapman and edited by Eddy Fifield, the short gracefully mixes footage of Lee’s time in America in the ’80s with his life now, on a farm in Taranaki, on the west coast of New Zealand’s North Island.

There’s much writing already about Lee as a skater — so let’s talk about filmmaking. There’s no flab on Fifield’s edit. It’s all essential to crafting Lee’s persona for the audience, right down to the opening seconds, which see a skateboarding dude (being coached by Lee) fall right on his side in a skating bowl in front of us and Lee joking and prodding at him from the railing.

But just as the trick to skating a bowl is keeping your speed, so too does Chapman plow ahead unobstructed through Lee’s history, and personal philosophy, and right ahead to where he’s at now. Kelly Chen, as director of photography, doesn’t get many opportunities to flex her muscles, but the final shot, of Lee in a field at his farm playing guitar and singing beside Tina Tiller’s stark, beautiful end titles design, is as gorgeous a shot as they come. The skateboarding photography isn’t as showy as, say, Skate Kitchen or Betty, but it searches for and unearths the “heaps of flair and humanity” that Lee says he tries to put into his skating.

As all skateboarding movies are, Lee Ralph has a buoyant, scraping kineticism to it, even in the footage from the ’80s, tracking Lee as he kills it on the ramps, or getting a closeup of his wry yet humble smile before he holds his board aloft for the crowd. Juxtaposing this elegantly is the following shot, which isolates Lee away from the noise and the ramp and gives you a look at him playing guitar in a loft, this down-to-earth, chill guy Lee still is — a guy who, by his own admission, only ever thinks about skateboarding and guitar.

Scratched: Lee Ralph is available to watch for free on YouTube.

Joutel (Alexa-Jeanne Dubé)

Joutel, a French-language short that played on day five, is about discoveries and rediscoveries. Specifically, the discovery of a dead raccoon in Gérard’s (Pierre Curzi) leaf pile, and the rediscovery of a childhood home when Gérard and Jocelyne (Marie Tifo) go back to the namesake Joutel to bury the raccoon.

The third short from Alexa-Jeanne Dubé, who is also an actress and writer and who wrote Joutel as well, is brimming with confident direction and faith that its bizarre elements will roll together into a satisfying snowball of a short film — or at least, that they’ll be whimsical and melancholy enough to be memorable.

Joutel is a deeply weird film. Honestly, I’m not even sure if it makes sense — I am not Canadian, so much of the cultural context is lost on me — but the short is so palpably sad and upsetting that it’s extremely hard to watch once, let alone twice, so some of my questions about the plot and themes will have to go unresolved. I get that Gérard and Jocelyne are supposed to be symbolic, or at the very least a fun couple to follow and the film has no shortage of French weirdness up its sleeve, but man, it’s hard to watch any old person, fictional or otherwise, do things like cradle a dead raccoon, as Gérard does, and whisper, “I’m scared of dying.” Like — f*ck, man.

Among the strange touches in Dubé’s film are an orange glow that emits from Jocelyne’s body and seems capable of reanimating the dead; a wonderful, fun use of split-screen throughout, aided by the precise timing of editor Marie-Pier Dupuis; and a wheelchair-bound stranger (Peter James) who pursues Gérard and Jocelyne as they journey through the autumnal Canadian countryside to bury their dead raccoon. (Just as Canadian winters are perfect for dystopias, autumn is the perfect season for Joutel — a season of dead things and change, cozy sweaters, and stiffening earth.)

The Joutel in question is a real place. The title card says “1965–1998” as though it’s an epitaph. The lifespan is Joutel’s, from the time it was established around local gold, copper, and zinc mines, to the time it was completely abandoned. The main street image on Wikipedia is, coincidentally, the filming location for Joutel’s finale.

With two moving performances at the core from Curzi and Tifo, assured direction from Dubé, and a supremely depressing score from Pierre-Philippe Côté, who is known best perhaps as the composer of the recent Zoey Deutch film Not Okay, Dubé’s film succeeds as an exhumation and exorcism of a ghost town, as well as a statement on the importance of survival. “We aren’t dead!” Gérard yells at the stranger at the film’s end. The framing situates them in a tableau, alone on a vacant lot in an abandoned town, the defiant standing above the graves of the past.

Ten Degrees of Strange (Lynn Tomlinson)

Johnny Flynn and Robert Macfarlane’s “Ten Degrees of Strange” is exactly the kind of 2010s falsetto–enhanced earthy indie folk I live for. From their 2021 album Lost in the Cedar Wood, “Ten Degrees of Strange” is a mythical fable about the flight from a black dog, and the music video dramatizes that gorgeously.

Director and animator Lynn Tomlinson bring her unique clay-on-glass style to the music video, which is dazzling and impressive, bringing the story to life like a series of rapidly flickering oil paintings — one thinks of Loving Vincent, the film composed entirely of oil paintings, but perhaps that’s just because Tomlinson’s style perfectly evokes the twirling, cloudy branches and oceans of grass that characterize Vincent Van Gogh’s landscape art.

The song, though literally about trying to outrun a dog, can be about any number of things one is avoiding — and given that this was a pandemic production, it probably best symbolizes stress, anxiety, or depression. And Tomlinson’s fantastic, dynamic animation brings all sorts of mythological and Biblical allusions to the table to dramatize that. From the relentless animal imagery — the main character is transmogrified into a deer, crow, and seal, and barn owls and voles also make appearances, plus the dog itself — to a massive flood, the video is rich with intertextuality. That’s not to mention the clay-sculpted look of many of the shots — “man born of clay” is a fairly common origin story in myth and religion, isn’t it?

Tomlinson’s use of clay is a perfect fit for the song, too. Its malleability makes it the perfect medium for communicating a story about a character always on the move — “Got this old bag of bones through seven time zones,” Flynn and Macfarlane sing — and who seems to outrun his pursuer at every turn. The video is a poetic meditation on nature in general, particularly in stunning transitions that see a man become a deer, or see the black dog sidewind out, blur into a black S, and become a rolling river.

Ten Degrees of Strange won festival awards for mixed media and visual design. Ten Degrees of Strange is available to watch for free on YouTube.

Fanmi (Sandrine Brodeur-Desrosiers and Carmine Pierre-Dufour)

On the surface, Fanmi is about a routine visit of a mother to her daughter after the daughter experienced a heartbreaking breakup. But it soon becomes apparent that the mother has other motivations for wanting to visit — that she has a life-threatening condition and is seeking to… what? Make amends? Find a way to tell her daughter? Or just see her again, before things take a turn for the worst? Even once the big reveal comes — that the mother is not well — Fanmi retains its mystery and dreamlike rhythm.

Co-directed by Sandrine Brodeur-Desrosiers, a trained musician, actor, and writer who’s directed over 15 short films and has a feature — Pas d’chicane dans ma cabane! — due out this year, and Carmine Pierre-Dufour, who also wrote the film, Fanmi has a smooth, naturalistic warmth to it. It’s a very autumnal picture — and not just because of the cold weather, awkward family conversations, and great scarves and sweaters. Like Joutel, Brodeur-Desrosiers’ and Pierre-Dufour’s short is about renewal and discovery, though Fanmi has more dramatic and tragic discoveries in mind.

As Martine and her mother, Monique, Marie-Evelyne Lessard, and Mireille Metellus are magnetic presences. Little is said between them, yet there is silence in that gulf. And because so much of the short is dependent on what is unsaid rather than spoken, Lessard and Metellus are able to communicate pages of emotion and backstory with a glance, an eye shift, a far-off stare. A two-shot of the women sitting on a bench in the woods, or a shot through a window at night, provide clean prosceniums for tender conversations, the film taking on the dimensions of a play under cinematographer Léna Mill-Reuillard’s careful framing.

The 14-minute French-language short, which showed on day six of the festival, is bittersweet, especially in the details of how this Haitian family shows love — mostly through cooking. The daughter serves her mother a meal when she first arrives, but her mom politely picks at the plate, not really eating. Later, they make djondjon together, and the tight framing of the two women together in the kitchen evokes a companionship through imagery that the characters hardly ever broach with their words.

On My Way / Neige (Paule Beaudoin)

It’s hard to say if I’ve ever seen anything like On My Way before. At least, the way the film communicates trauma, pain, and death is something I don’t think I’ve ever seen portrayed on-screen quite like this.

The film, a nine-minute French-language short, is writer-director Paule Beaudoin’s second short film. It opens on a snowy street over the sounds of yawning, the windshield wipers thumping, and a screech that implies a car crash. But we see very little, only the gently falling snow.

When the man, Jules (Benjamin Déziel), wakes up, he’s covered in snow, and he’s in his home with his daughter, Sara (Olivia Leclair). Vincent Gonneville’s warm photography favors the dim yellow light of the nearby lamps, which suggests both paternal warmth and conjures images of a roaring fire just off-screen. Déziel and Leclair are touching in the way that Jules feels out this mundane night with his daughter, while in the back of our minds, the opening stinger of the unseen car wreck lingers.

Jules finds in his daughter a respite from the cold and from his oppressive thoughts, and his daughter finds the same thing in him — she can’t sleep, so she articulates a dream about a malevolent snow monster to Jules. And Jules, a comic book artist, sketches out the dream and suggests an alternative ending — he saves her on the back of a sled, and they ride off down the hill, away from the snowy giant.

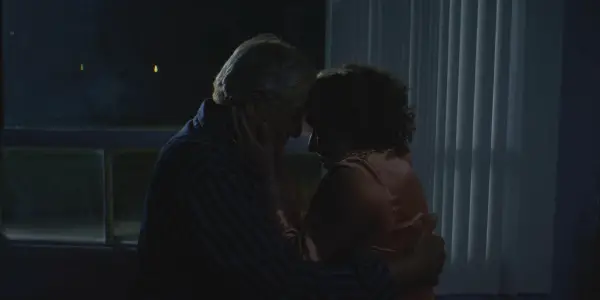

On My Way would be profound if it were chronological — a father kept awake remembering a tragic car wreck and seeking solace in his daughter. But Beaudoin’s script instead gives us a twist, one that may not sink in with the final shot of a car crash in the middle of the desolate road — that Jules, in fact, is dead, transported into a sort of bardo in which he’s allowed one more conversation with his daughter before his soul moves on. On a second watch, Beaudoin’s dialogue is more revealing and cleverly double-edged, Gonneville’s cinematography more morose, and Déziel’s and Leclair’s performances as perfectly affectionate, tender, and close as they are on a first viewing.

On My Way won the festival awards for directing and cinematography, tied with Cansu Boğuşlu for Down From the Clouds on both counts.

Conclusion:

Each day also saw a showcase film and several features. Day four saw L’autre Rive from Gaëlle Graton; Planet Prescription by Dayna Reggero played on day five; and Two Eggs, Scrambled from Melissa Dimetres played on day six.

On the feature film side, day four saw screenings of Angelina Jolie’s Cambodian war drama First They Killed My Father and Maya Forbes’ Mark Ruffalo-Zoe Saldana comedy drama Infinitely Polar Bear. Day five saw showings of Alice Rohrwacher’s Italian Cannes contender Happy as Lazzaro and Mélanie Laurent’s 2014 French coming-of-age film Respire. On day six, FFF7 screened Radha Blank’s breakout Netflix film The Forty-Year-Old Version and Emma Seligman’s celebrated MUBI release Shiva Baby.

Learn more about the Femme Filmmakers Festival and see their 2022 selection here.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Film critic, Ithaca College and University of St Andrews graduate, head of the "Paddington 2" fan club.