FEAR ITSELF: A Half-Hearted Exploration Into A Fascinating Subject

Laura Birnbaum is a proud film critic and writer from…

Every second, they’re poking you, prodding you, trying to get you to look in a certain direction or feel a certain way. Before long, they have you exactly where they want you. You can tell yourself it isn’t real – tell yourself it’s all just manipulation, but it’s no use. As you sit there and take it all in, you feel the fear they want you to feel.

“They” are horror movies, and these are the words recited at the start of Fear Itself, an experimental “documentary” film (we’ll get to the reason for those quotations later) by director, Charlie Lyne. Throughout the film, a wearisome narrative voice waxes rhapsodic about the role of horror movies in her life, while correlative clips from such films fill the visual space. As a whole, the film acts as spoken word recited against the backdrop of thoughtfully selected scenes from movies. With a premise as intriguing as this, the real question is: do these melancholic meanderings add up to something?

The answer is not so simple (oh, but would that it t’were so simple). Thus, before diving into what worked about Fear Itself and what didn’t, let’s try to indulge your spirit of inquiry, and look at what this film sets out to achieve and how it sets out to achieve it.

Between Two Windows

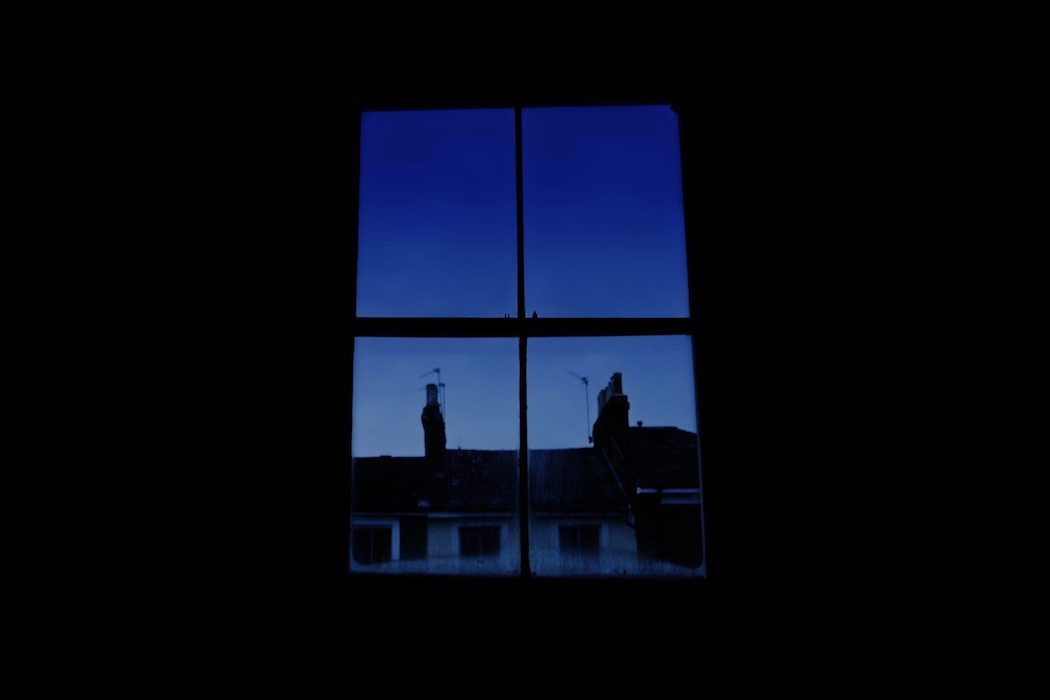

The film opens and closes with an image of a window. This is the only shot outside of the 80+ films Fear Itself features that is original to the film. It’s a striking shot – we are in a dark room facing a closed window from a low angle, looking out at the neighboring roofs and dusky sky. It feels as though we are getting our narrator’s visual perspective, as she begins to verbally process her thoughts.

The image is eerie, as could be the primary sensation-descriptor for the remainder of the film, but outside of the ‘inside looking out’ sense that it elicits, it foremost serves, or tries to serve, as an ephemeral sojourn outside the flood of moving images of terror and suspense that it contrasts. However, due to the near two hour space between these quiet window moments, its minimalist weight is lost to the mere length of what precedes it and what follows.

That space in between is filled to the brim with scenes of all kinds – from gore to terror and suspense – the whole of which is edited beautifully and bound together by a disconcerting score that hums and pulses throughout. Lyne utilizes a wide variety of clips that span over a hundred years of horror history, including an impressive abundance of esoteric and foreign language films (fear not, I added the ones unseen to my Letterboxd watchlist, as I encourage you to do as well).

Faults and Where to Place Them

I said that the answer to the question I posed at the beginning of this article wasn’t so simple, and it’s not. Almost everything about Fear Itself works – from concept to scene selections, to editing and the score – all except for the core thing it sets out to do; to explore why she (we), through film, seek out the sensation of fear in the most dire moments.

The well-chosen and thoughtfully correlative clips serve as a homage to all the films being featured, though not much else. The words spoken over them quickly became a hindrance for two main reasons: 1. What is being said is not of much value and 2. The slow pace in which the narrator speaks made it feel like I was sitting in traffic, moving slowly every couple of minutes, only to find myself inches ahead of where I was in the first place.

The narrator, whose face remains unseen, talks about how she is drawn to horror movies after being in a car accident, trying to correlate this “real-life” trauma she experienced with her need to cope through film. Do you remember those quotes around the word documentary above? Well, after a little research, it seems that the narrator is a fictional character developed and played by Amy E. Watson.

While this is not a huge deal, I admittedly felt a bit played by the “documentary” classification. I usually love unreliable narrators, but this is something else entirely. The film had transformed itself from being an authentic and deeply personal genre study (that went on too long) into an illusionary and incomplete work of fiction (that went on for far too long).

Oh the runtime, how I felt you so. Despite being drenched in the richness of one of my favorite genres, it started to feel like a laborious chore to get through. While there are moments of sincere profundity that genuinely stirred me and gave me reason to think about my own relationship with fictional horror, these moments were disappointingly few and far between. The insight within the film’s overall message, epiphanies and all, could easily be condensed to about 20% of the film’s run-time.

Exquisite Corpse: The Fusion of Fear and Pleasure

People are fascinated by the visceral sensation of being scared. Real life vulnerable fear is one thing, but when a screen is placed between us and a fictionalized version of that same thing, the screen then becomes a barrier between it and us; creating a safe space to feel and process out fear without the consequences. Watching a horror movie after dealing with real trauma has this wild potential to go back to that awful feeling and place pleasure on it – kind of like a really weird Freudian band-aid. Therefore, what we are ultimately seeking is healing through knowledge.

Eugene Thacker explores the varieties of esoteric thought as it applies to horror in three volumes, beginning with In the Dust of this Planet: Horror of Philosophy Vol 1. He suggests that:

We look to the [horror] genre… as offering a way of thinking about the unthinkable world. To confront this idea is to confront the absolute limit of our ability to understand the world in which we live.

Whether or not watching horror movies is an effective form of coping, I’m not sure. I doubt that it will be prescribed by psychiatrists any time soon, but the fact remains that some people (*ahem*, me) turn to it, whether or not they (I) fully understand why. Horror movies have always reflected the neurosis of societal pain and fear, but it absolutely reflects it back at you. It’s up to you as to what to do when confronted by it.

Conclusion

This propensity to watch horror movies as a way to cope with a traumatic experience is something that I certainly relate to, and as studies seem to show, as do many of you. In the words of Stephen King, “We make up horrors to help us cope with the real ones.”

I don’t know if I expected Lyne to get into the Id or into hierophantic principals, but let’s just say that it would have been nice. Perhaps my somewhat banal experience with Fear Itself is a classic case of expectations vs. reality. Was I Joseph Gordon-Levitt getting excited about going to Zooey Deschanel’s party? Are my expectations to blame?

You tell me, dear reader. Please watch Fear Itself and tell me what you think. Will you search for the logic in it all or simply, “feel the fear they want you to feel?”

Fear Itself is currently available on streaming platforms in The UK and does not yet have a set release date in the US. Check out the Fear Itself Official Film Site for more information.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Laura Birnbaum is a proud film critic and writer from Chicago. When she's not watching independent horror films, she's likely smoking a cigar on a rooftop somewhere, thinking about which indie horror film to watch next.