Meeting Fear With THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT

Tessa is a writer living in Boston, where she spends…

It’s easier for me to write about movies I hate than movies I love. When I don’t like a movie I can push it through the machinery of my brain and form it into something with a shape; when I love a movie, everything I say pours half from my heart and half from my stomach, and the resulting red globs are soft, amorphous, and vulnerable. Teeth and tongue in a little wrapped package.

The Blair Witch Project is one of my favorite movies of all time, from any genre. I talk about the Blair Witch like she’s an old friend who just gets me, even after all this time; she knows what scares me, but beyond that, she encourages me to revisit my general relationship to fear. I talk about this movie so much and so intimately I sometimes forget that’s what it is –– a movie, and not a living, breathing loved one. What we have feels like true love.

A Horror Icon Takes Its First Steps

The Blair Witch Project was filmed in 1999 with a famously low budget, and would go on to explode in popularity and cement the found footage format as a horror staple. The film’s introductory title cards inform us that its footage was salvaged from the sparsely populated Burkittsville, Maryland, a year after three college students wandered into the town woods and disappeared. The rest of the movie unfolds through the scraped together footage, with lots of shaky cam, and very little obvious high-stakes action.

Our protagonists (leader Heather, and her crew/classmates Mike and Josh) enter the woods with plans to shoot a student documentary on the local legend of Elly Kedward, the Blair Witch. The documentary project morphs from a scholastic endeavor to a coping mechanism as the three become increasingly lost in the woods, begin to sense that they are being pursued, and finally succumb to whatever dark power has been following them through the woods.

Quick confession: I’m scared of lots of things. As a horror fan, this is lucky or unlucky, depending on your perspective (my mother would say luck has nothing to do with it, that it was the movies that made me this way). In my most satisfying experiences as a horror viewer, the films lay out this kind of deep fear delicately, creating a path that can lead to catharsis, or fascination, or a deeper understanding of myself as a viewer. If there is a positive side to being a scaredy-cat horror fan, at least it indicates you are willing to approach a movie with an extremely open heart.

This sort of close encounter between viewer and film is a lot harder to accomplish when the audience has their emotional barriers up, and there have been plenty of emotional borders erected against the The Blair Witch Project since its release. Almost any reflection on this film will dissect the War of the Worlds-esque impact it has on early audiences, who, not yet inundated with found footage films, wondered if the story they were seeing could possibly be true. Even years later, focusing exclusively on realism can become a kind of armor. You can’t possibly be affected by a film if you’re busy searching for holes in its plausibility.

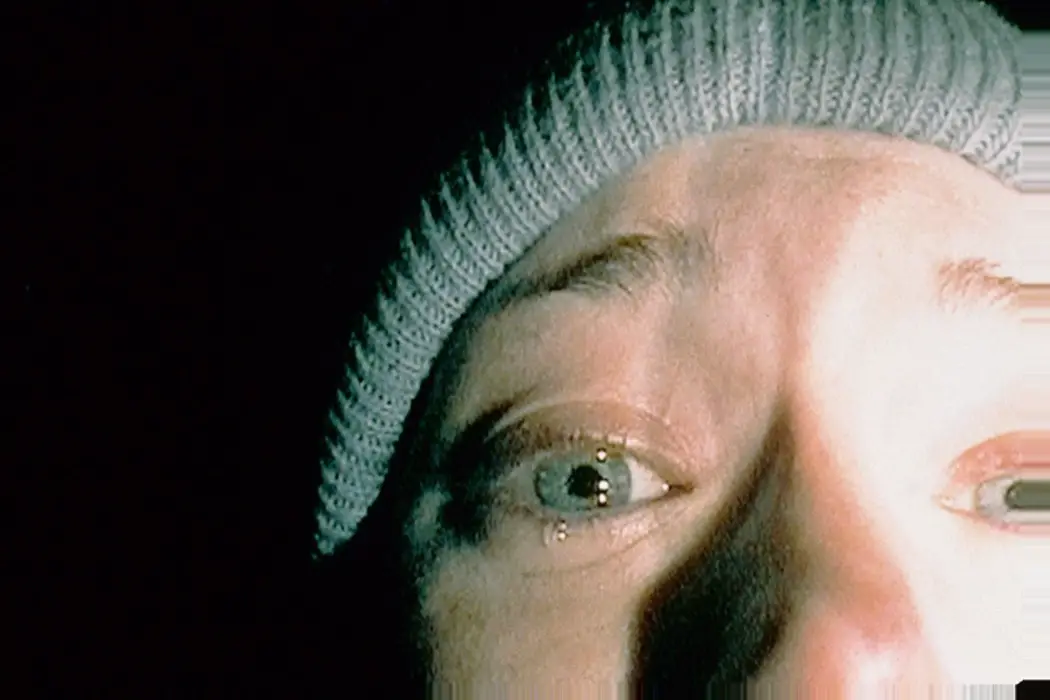

The fact that this attitude persists is too bad, especially considering how aptly The Blair Witch Project works within its parameters, manipulating its limited budget to encourage intimacy. Without the aid of high quality equipment or studio lighting, your eyes have to search the screen, seeking scares that appear for only a moment, if at all. Lean in, if you’re willing; keep leaning; pretty soon you and the film are nose-to-nose.

I was five years old when The Blair Witch Project was released, so I was spared this type of “gotcha” viewership. From the start, I knew this film as a film, with grainy footage that was grainy on purpose, and lines of dialogue that were largely improvised. Still, I had my own armor up. On my first watching of The Blair Witch Project, I misattributed its potential for fear. I assumed, considering the camping-gone-wrong narrative, that it belonged to the category of horror that considers the wilderness an alien landscape; I also assumed, as someone who grew up in the woods and is not afraid of them, that it wouldn’t quite land with me.

Shattered Reality and Loss of Identity

But there’s more to this film, and that something more is the reason it still hits me so hard. Heather, Josh, and Mike walk all day and end up in the same spot where they began; they pitch a tent and wake up to find it surrounded by perfect little piles of rocks; the find twig dolls that don’t fit any of the legends they’ve collected. Being lost in the woods with limited food (and cigarettes) is scary, but more so is the knowledge that the woods are not behaving the way they are supposed to. There is someone else in the forest with them, breaking rules that are supposed to run deeper than human logic.

The feeling of reality cracking open is both terrifying and familiar. Some of us may have experienced this while processing the realization that our definitions of justice aren’t reflected in the political or social conditions around us, and that those people who are meant to represent justice reject it wholly. If you are okay with the rules of reality as you understand them, it’s not frightening to follow them; if you find the rules are different than what you thought, or that the rules seem to have vanished entirely, that can be incapacitating.

Remove every whiff of the supernatural from The Blair Witch Project and this theme remains. While Heather is still emphatically denying that the trio is lost, she falls back on the belief that truly bad things don’t happen, not like this, not to kids like them. She has two persistent arguments: that they aren’t really lost because she understands where they are; and that they can’t really be lost, because this is America.

National identity is one of Heather’s core methods of self-defense, but all of the characters draw upon it at one time or another. She reassures Mike and Josh that “it’s very hard to get lost in America these days, and it’s even harder to stay lost,” and revisits this idea in a later scene, insisting that Americans can’t stay in the woods indefinitely because “we’ve exhausted all of our natural resources.” Frustrated and pushing up against hopelessness, Mike walks away shouting America the Beautiful. When we cut to a new shot, Josh and Mike are singing together, but quietly, running out of the energy necessary to recite the words that are meant to evoke freedom and protection.

Facing actual danger, national identity won’t protect them, and neither will personal identity –– Heather makes this clear during her iconic monologue scene, in which she apologizes directly to the camera, swallowing each of her defining characteristics to take the blame upon herself. The film asks us to discard the cultural self, and then the personal self, and then refuses to provide an ending that would at least allow for some existential meaning.

The Continued Relevance of The Blair Witch Project

Fear of shattered reality is so deep and hard to articulate, it amazes me when it’s caught on camera. Film itself is a medium full of rules and logic and evocation, which makes it a less-than-ideal method of exploring true meaninglessness. A movie takes place within the confines of a screen, and it has inevitably been edited, and when the hundred-ish minutes run out, it’s over. The best any film can do is to represent meaning crumbling within its devised world.

The Blair Witch Project gets a lot of flexibility by creating a film within the film, using film language itself as a stand-in for other kinds of everyday logic. In one scene, Josh grows sick of Heather insisting on filming everything, and shouts his disbelief that even in the most terrifying moments she’s “still making movies.” Angry, scared, and tearful, she shouts back that the camera is the only thing she has left. At least looking through a lens, she can give herself the facade of control.

This moment is so overwrought it tends to mark my one good eye roll in the movie, but as I’ve been getting older, it’s been making a sicker and sicker kind of sense. It’s scary to remember that outside of the comfortable boundaries of socially accepted human activity, the universe is vast and unknowable. We are small, and most of the time we do what we’re supposed to do, and there is very little about our reality that we fully understand. Someday this world is going to swallow all of us up, and then the universe will swallow the world, and there will be no comfortable human reason for that at all.

As a species, we are hurtling toward destruction. We are designing our own unsurvivable conditions; with the recent UN climate report, this outcome suddenly feels closer and more inescapable than ever before. I would never make a claim about a 90’s horror film parallelling the precise existential dread of 2018, but I will say that, for me, the type of fear The Blair Witch Project represents will never be irrelevant. Digesting the idea that you might die without any satisfying resolution is hard, and at this point human history, we are being forced to do just that.

If you were to set up a spectrum of attitudes toward death in genre fiction, you could put movies about space exploration on one side, and The Blair Witch Project on the other. In the world of this film, there is no future in which humanity gets to shoot away in pursuit of new hope. Instead, we are reintegrated into the earth, in a fate that is less supernatural than hyper-natural –– inevitable, powerful, and wild beyond human understanding. A feral witch might not gobble me up, but eventually, the earth below me will.

Understanding the things that scare you is a kind of self-exploration. We turn the corner with flashlight in hand, anxious and shaking, but still determined to discover what’s hiding in the shadows. If you’ve seen enough horror movies (especially if you’re a jumpy person), there’s a good chance you have a grasp on your own sensitivities. Finding the perfect horror involves all the same joy as discovering any favorite movie, but sometimes with even a deeper level of resonance. So many boxes need to be ticked.

To me, The Blair Witch Project works, and will work forever, because it maintains an underlying philosophy that simply feels true. Some things are too much to grasp, and our concept of safety relies on us staying in a very narrow lane. From my comfortable couch, doors locked, this idea is intoxicating. Sometimes there’s nothing to do with your fear but fall in love with it.

Despite this, it’s the interpersonal relationships that ground The Blair Witch Project and make it interesting. There’s one more piece of philosophy here, one that movies like this need in order to function (and which I need to function, too, and will probably need to repeat to myself for the rest of my time on earth): death comes, and it can’t be stopped, but in the face of death, life still matters.

What do you think of The Blair Witch Project‘s approach to representing fear? Does it resonate with you?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Tessa is a writer living in Boston, where she spends her time eating falafel and falling asleep on public transportation. Her greatest personal goal is to learn how to allow someone to dislike horror films without trying to convince them they just haven't seen the good ones yet.