Camp. It’s a slippery term, easily applied to any grandly staged production by some and rigorously nitpicked and scientifically labeled by others. It’s a certain enunciation, a blinding dress, a glint in the eye. It’s all of that and none of that because camp is an artistic expression that exists outside of written language, one that stands in defiance of boundaries and hence can’t be captured by something as limiting as words.

I apologize up front. Most writing on camp slips into haughty digressions like this in the face of its own inadequacy, and mine inevitably will as well. This one, though, will also have breaks for gratuitous butts, which can’t be avoided when discussing the Fast & Furious franchise.

Yes, that continuously one-upping behemoth of a movie series about street racers turned international operatives loves its butts, cars, and family, a milieu that is generally met with a chuckle by audiences and critics alike. And why not? The franchise doesn’t take itself seriously at this point, and it’s never been one to waste time on complex themes when there’s nitro to inject into the engine.

Most openly acknowledge that it’s an overblown mess of manly men shouting operatic dialogue and making things go vroom while some women play along, a strange charm and a sense that it’s harmless fun protecting it from any sizeable groundswell of criticism or examination (don’t get me wrong, they get plenty of bad reviews, but few break it down with the vitriol that, say, the Bond franchise gets).

But I’m here to stick up for the big guy, to argue that there’s more to the Fast & Furious movies than a vapid exercise in immediate pleasure. In fact, there’s an unnamed current in them that we all get swept up in without having the vocabulary to name it: the Fast & Furious movies are camp in a way we feel in our bones but have been trained by decades of narrow-minded definitions to deny.

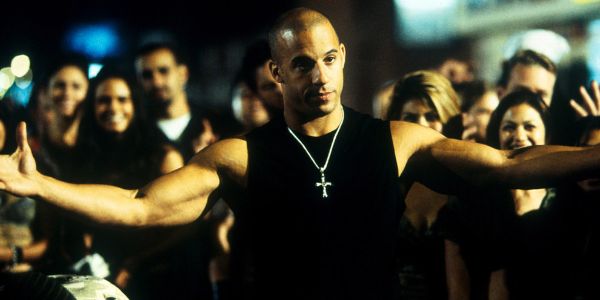

The slipperiness of camp has caused so many false connotations to build up that Vin Diesel strutting around in perpetually sleeveless shirts and droning out every line in a voice so deep you can feel it scraping the floor doesn’t even register as camp, which it should because it is. This deep denial robs not only the Fast & Furious franchise of its rightful place as one of the most successful examples of camp in pop culture, but more sinisterly it denies the potentially revolutionary function of its camp within culture.

Guess What? No One Understands What Camp Is

The inability to recognize camp in all its glory is largely a function of its limited definers. The definitive text is still Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp'”, an oft-quoted (a habit I will not be breaking) sketch of disparate thoughts and observations that deftly reflects the tone of camp but applies the narrow and frankly incorrect scope most still adhere to. Perhaps the most famous snippet pulled from her 58-point dissection is its last: “it’s good because it’s awful.” Sontag herself notes that the phrase is too vague to have meaning without the previous 57 points refining it, and yet that’s the quote that lives most widely in people’s minds. A more precise definition to pull, and one that’s more representative of Sontag’s essay, is “love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” As a basic definition, it’s a good one, capturing camp’s ability to key in on learned behaviors and blow them up until everyone can see just how learned they are, and it’s not at all complicated to see how a series that one-upped Diesel’s masculine display of beefiness with Dwayne Johnson’s fits in.

The issue comes as Sontag notes its history and gives examples, which she uses to frame camp largely as an aesthetic birthed and recognized by gay men. Again, most people probably make this connection in their heads whether they realize it or not, matching it with an effeminate nature or the outright overblown femininity they are associated with. Drag queens? Camp. Dresses so elaborate one can barely move? Camp. Jessica Lange screaming in American Horror Story? Textbook camp. Arbiters and providers of camp since Sontag have largely been gay men, and that narrow perspective has come to limit the otherwise loose and malleable power of camp.

I will note that gay men are a huge group of people with varied tastes and aesthetics, and there’s folly to lumping them, as with any group, together, but for the sake of discussing broad pop-culture lens I’ll move forward by discussing gay men in reference to the effeminate variety that once lifted up Judy Garland and now push Lady Gaga to revered status.

Despite the widespread connotation brought on by associating camp with these gay men, it is not, by any valid definition, related to femininity. It’s true that the exaggerated expression of femininity that is most easily recognized as camp is artifice, nothing but outward cues that this culture at this time has designated as feminine. But there’s also artifice in how we communicate masculinity, in how we express the mix of the two many of us feel within ourselves, and in how we get across a variety of identities that reach far beyond gender.

All of this artifice makes prime territory for camp, but considering the way we should walk, talk, dress, do our hair, etc. is drilled into us by nearly all aspects of culture, it’s hard to recognize the artifice unless we actively rub against it. The brand of gay men who have largely defined and made camp rub against only specific aspects of the wealth of artifice in society, and as more diverse people claim their work and that of others as camp, the true extent of what it can be, the delight in all of what Sontag called the “theater of life”, can be recognized and placed under its wide, probably bedazzled, umbrella.

Premiering just two years before Fast & Furious hit us with their first round of unnecessary butts is a film that took direct aim at doing just that, Jamie Babbit’s pastel blue and pink extravaganza But I’m a Cheerleader. The lesbian romance at a ridiculous gay conversion camp was, as Babbit put it, a “feminization of the camp aesthetic”, which she meant more as adding the genuine emotion she thought was missing from the domineering gay male-driven version of camp. What others have latched onto in the ensuing years, particularly as it came under renewed appreciation at the 20th anniversary of its release, was in what her camera was capturing as camp. The staple of lurid, lingering shots of female bodies in movies as a whole, a side effect of the industry being dominated by men, was reclaimed in its opening moments by shots of female cheerleaders from the perspective of the titular closeted lesbian protagonist of the film, Megan. I’ll let Jessica Moore in Mubi’s ‘Visualizing Liberation in “But I’m a Cheerleader”’ take it from here:

“Though the camera lingers on sexualized bodies, because this scene is from Megan’s point of view it also elevates feminine detail: intimacy, pompoms, pleats of polyester. Thus, although this sequence recognizes a male, especially American, sexual role-play, it omits men from their own fantasy; it is reconfigured to include the gaze of women.”

The specificity of what Megan is attracted to here is its own bit of camp, the intense zoom on points of appeal that are typically aimed at men but have been funneled viewed through a queer woman’s eyes are overblown to highlight the difference (and yes, it includes butts). The film continues on with the amplification through skewed perspective, taking aim at so-called lesbian traits (vegetarianism! Melissa Etheridge!), of gender stereotypes (girls must iron and meticulously scrub floors), and of the too cool and seductive lesbian dream girl (the succulent smoking of Clea DuVall). This makes for camp that is as much about highlighting the oddities that queer women notice (and gay men might miss) as it is about pointing out this perspective’s previous absence, planting its flag with a display so gaudy it’s hard to miss even as it consciously pushes the boundaries of what camp is supposed to be.

Other queer women have picked up this baton and run with it, forming a mini-movement that’s infiltrated all levels of entertainment. Mikaella Clements outlines the breadth of this in her article “Notes on Dyke Camp”, some of her quick hits being Janelle Monáe’s vagina pants, the Instagram account Butchcamp, and Kate McKinnon, full stop. But even these examples are limited by their queer perspective, and the death grip the queer community has over camp is ultimately choking out much of camp’s ability to highlight and bring into question artificial social constructs. So let’s expand it to straight men ogling butts, shall we?

Make Way For The True Revolutionaries

The Fast & Furious series, a smorgasbord of souped-up cars, extreme stunts, and guys being dudes, is so awash in cishet men’s masculinity that camp’s association with the queer and the feminine has seemingly filtered it out of contention. Yet many of the ways its men strut through the series is pure performance, leaning on displays that dominant culture would have you think are natural but are, in reality, pure artifice.

In case this is confusing, let me give a personal example. When I was in high school I dragged myself around the mall trying to find a polo shirt for my department store job. I recoiled again and again at the delicate options in the women’s section until my fed-up mom brought me one from the men’s and proclaimed that no one would notice the buttons are on the other side. This was the first time I consciously realized that buttons on men’s clothes are on the right and women’s are on the left, a gender signifier so unmoored from masculinity, femininity, being a man, being a woman, being a nonbinary person, from being anything besides a rule that had subconsciously implanted itself in my brain and had caused my masculinity revolt against the polos I was finding in the women’s sections (I wore the men’s polo, was quite happy, and no one said a thing).

The world is full of inane ‘which side of your shirt are your buttons on’ signifiers, and it’s these that the Fast & Furious series relishes and blows up, exuding a hyper-masculinity so overwrought that it shoots past cool and goes straight into camp.

Early on this seemed to be a calibration issue, with the movies seeming to genuinely think their swaggering men were the epitome of guys you should aspire to be like. When the main characters assemble for the first time in 2001’s The Fast and the Furious the communication of alpha masculinity, from the suggestive stuck out belt ends to their shoulder-swaying strut is all operatic tough guy-ness that, naturally, ends in a fight set to the on-the-nose tune “Watch Your Back” by Benny Cassette. More posturing is called for as Paul Walker’s Brian is made to prove his worth to the rest of the group, the flame-shooting car races with women (and their butts) lining up for the winners being pure exercises in hierarchical battles, testing grounds for worth, loyalty, and respect (because driving fast connotes all of this). By the time Brian earns his place and the girl, you’ve been pummeled with so much performative machismo that its garish disregard for the measured way people communicate in real life either leaves you frazzled by or chuckling with the thrill of camp.

As the series moves on it hones in on this unintentional exaggeration as the source of its charm and makes it very intentional, managing to thread the needle of having real, human men (for men are not its target) while its masculine displays morph into acts of heroism that are constantly one-upped until the joke is that reality has been abandoned, its every affectation a gaudy display meant to bring its audience together in recognition of its silliness. The cars get bigger and faster until they aren’t even cars anymore (and yes, there’s compensation jokes), muscled arms expand as if in competition with each other, and what seems to be the ultimate display of heroism, a man launching himself through the air while cradling his beloved, goes from a trucker bailing from a speeding vehicle with his iguana nestled softly in his arms to Johnson diving with his partner from a building high enough to pancake their bodies, but they’re both fine because he is a man, I guess.

Fast & Furious has taken masculinity as its theme not to provide a detailed exploration of what it means to live within its boundaries but to revel in everything it is to be the main beneficiaries of its construct, to be the big guy with money, toys, and the ability to change the world. It’s a fantasy land of traditional masculinity as the apex of society, which yes, is exactly what society tells us it is, but by placing masculinity on a pedestal built entirely on affectations so absurdly inhuman that it wobbles from the gleeful laughter of its own audience, Fast & Furious shows it for precisely the house of cards that it is.

Sontag referred to camp as putting things in quotations, that a lamp becomes a “lamp” and a woman becomes a “woman”. She didn’t expand that out to a man becoming a “man”, despite all the glorious artifice that the Fast & Furious series has found to wallow in. How its “man” has gone unnoted by purveyors of camp is hardly a mystery. While culture at large wouldn’t consciously register the quotes because we’ve been trained to think of it as normal, those looking out for camp have designated it as too strong a target to aim for and filtered it out as well. As J. Bryan Lowder put it in his often brilliant dissection of camp for Slate:

“Camp allows us to see the paradigms in operation all around us and recognize them for the arbitrary and possibly undesirable doxa that they are. But that power of critique is also the thing that makes true camp ultimately incompatible with any notion of normality, for normality, like masculinity, is too dependent on going unquestioned to bear camp’s dissecting gaze.”

How sad, to imagine any of the fragile social constructs that make up normality being outside of camp’s range. Isn’t normality constantly shifting below us? Aren’t aspects of it always being pointed out as absurd and worthy of being left behind, things that simply are the way they are now things that were the way they were? Is not the “dissecting gaze” of camp a tool that can bring the whole concept of normality (and masculinity, for that matter) crumbling down?

To Lowder’s credit, he goes on to recognize that camp as he describes it would likely become something much more, perhaps through being led by groups other than gay men. What he seems not to have recognized was that their were already groups taking aim at all-powerful masculinity, that dyke camp (with its inherent but not exclusive fascination with masculinity) had picked up gay men’s fumble and straight men themselves were bringing it in for a touchdown.

Lowder was correct that masculinity, sitting atop the world, would be a hard one to wrench from its unquestioned perch. And at the risk of tooting their own horn even further, perhaps the only ones that could widely proselytize about the house of cards it sits on were cishet men. That we got a group so fascinated with their own construct is pure luck, and that they explored it as camp through one of the biggest movie franchises in the world is a minor miracle. Now we just need to speak of it so we have a chance at knocking it down.

Do you think Fast & Furious qualifies as camp? What do you think defines what camp is in film? Let us know in the comments!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.