Fantasy Science Pt. 19: GATTACA, Genetic Engineering & CRISPR

Radha has a PhD in theoretical quantum physics. Apart from…

Genetic engineering. CRISPR. Designer babies. Have you heard terms like these flying around the science fiction sections of the film/TV world? Have you ever wondered just how accurately these films portray real science? Well, my friends, today is your lucky day: this column, Fantasy Science & Coffee, aims to bridge the gap between science and science fiction in films and popular culture. My hope is to explain things in a fun way – like we’re chatting over coffee.

You may be thinking: who is this person, why does she think she can explain science, and why the heck would I want to have coffee with her? Well, I’m Radha, a researcher in India, who recently submitted a PhD thesis in theoretical quantum physics. I quite like hot beverages. I’ll also pay.

In this nineteenth part of the series published on the second and fourth Tuesdays of every month, we are going to look at a biotech tool called CRISPR that may have the potential to bring the future depicted by Gattaca to life.

Gene Editing in Gattaca

Imagine a world in which you can select whether your unborn child has green eyes or a propensity for mathematics. A geneticist shows you four fertilized eggs, “pre-embryos”, each with a unique set of optimal traits and no predisposition to conditions like premature baldness, myopia, or addiction. The geneticist says something like this:

You want to give your child the best possible start. Believe me, we have enough imperfection built-in already. Your child doesn’t need any additional burdens. And keep in mind, this child is still you, simply the best of you. You could conceive naturally a thousand times and never get such a result.

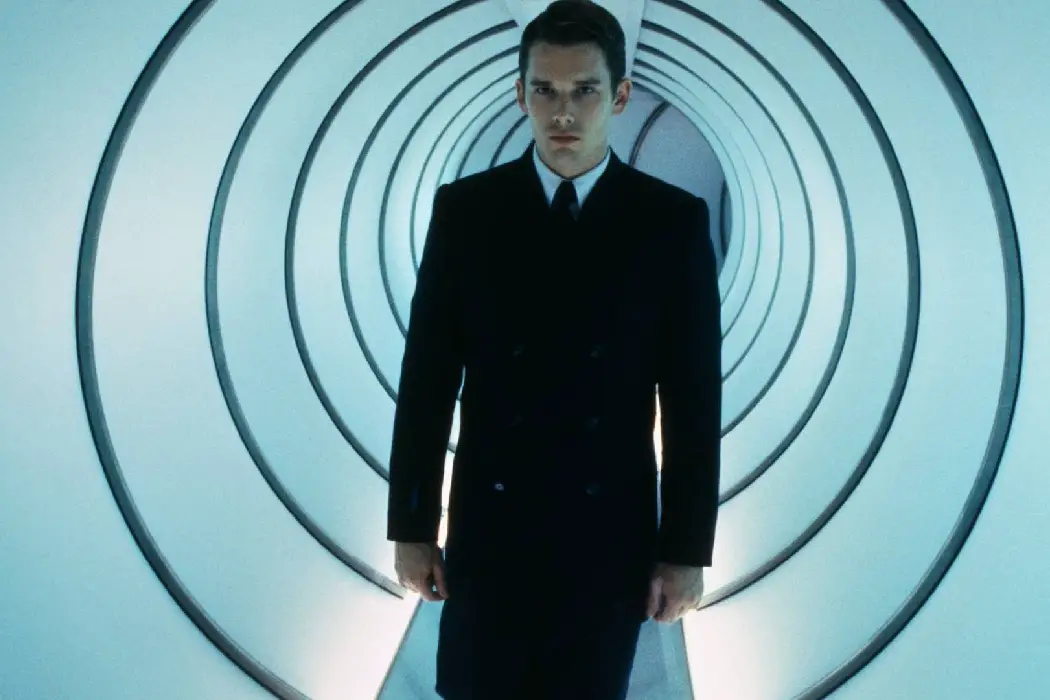

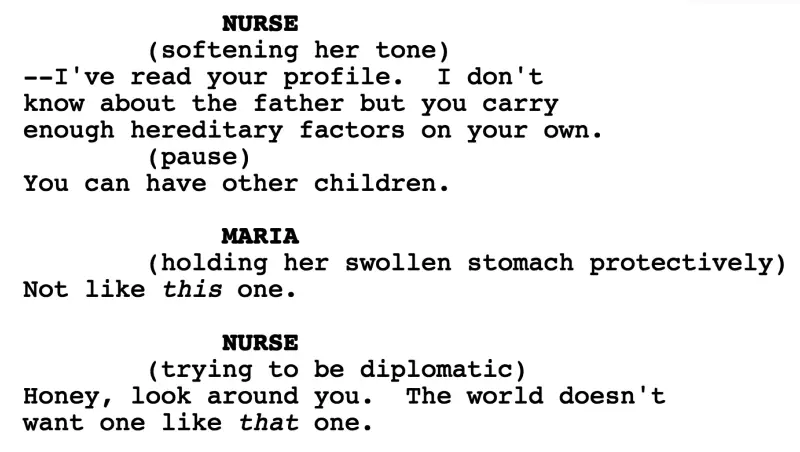

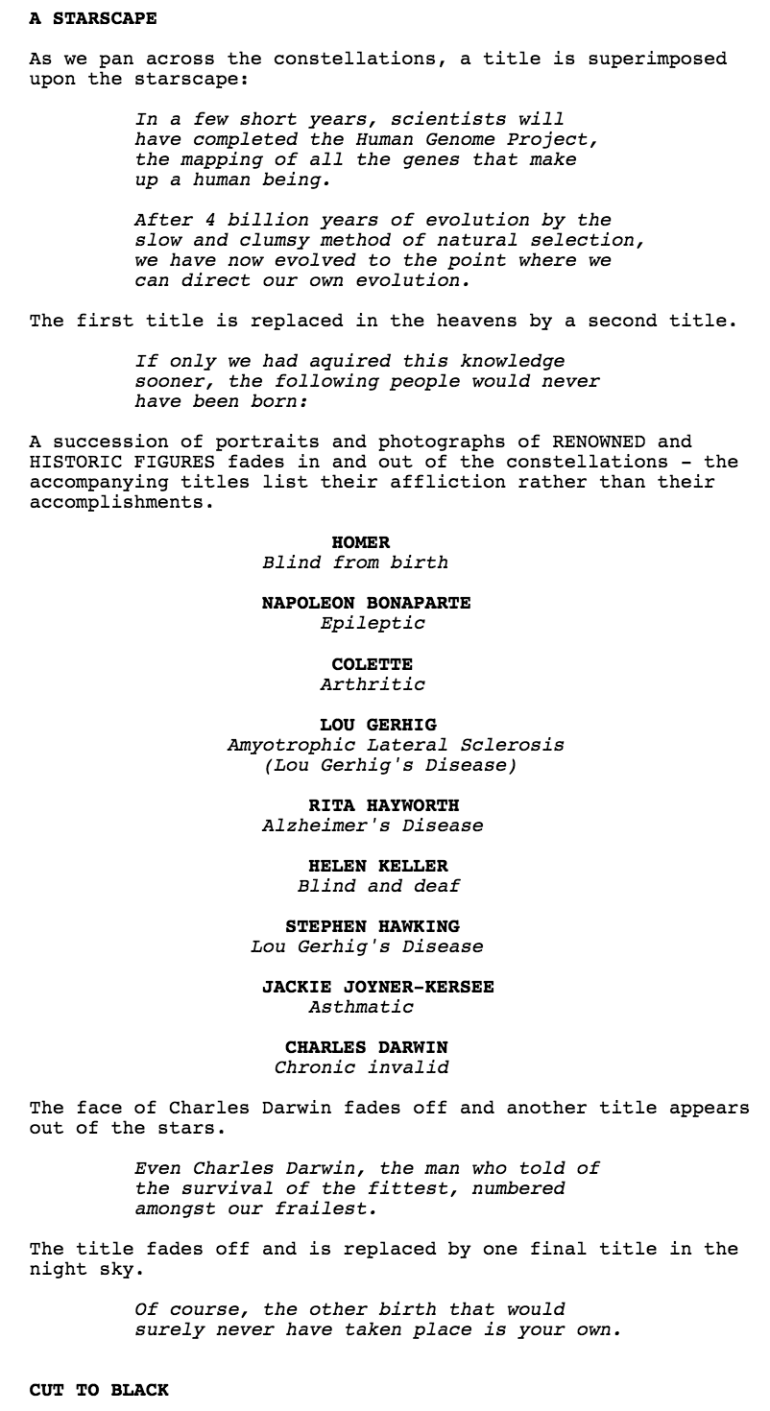

This is exactly what happens in the 1997 science fiction film, Gattaca, and this is exactly what the geneticist tells the parents of a boy named Vincent when they decide he needs a baby brother. Vincent, however, is a product of love, conceived in a Buick Riviera, and not in a petri dish. The story follows Vincent, genetically ‘inferior’ in the eyes of society, an outcast who wants to become an astronaut but by default cannot. Interestingly, in Andrew M. Niccol’s original script, a nurse tries to convince Vincent’s mother to abort him before he was born:

This never made it to the final cut, but reflects well the society depicted in the film. Vincent eventually takes on the persona of a crippled genetically ‘superior’ Jerome Eugene Morrow, henceforth known simply as Eugene. The new Jerome wears lenses, uses tiny pockets filled with Eugene’s blood under fake fingertips for fingertip blood sensors, carries packets of Eugene’s urine in his pants for random urine tests, along with a number of other clever tricks to make his new identity solid as he rises through the ranks of the space agency Gattaca.

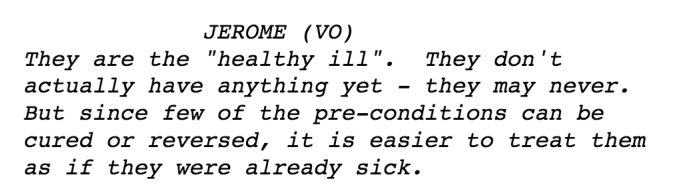

No one suspects him because a genetically inferior human who may develop a heart condition later in life could never have achieved so much, of course. There’s a piece in the original screenplay that I feel beautifully captures the stark dichotomy between the the underdog and the privileged:

The frightening thing about this film is how believable it is. Humans are quick to point out differences as opposed to similarities. And now, more than ever, the world is on the cusp of mainstream genetic engineering thanks to something called CRISPR. It’s a technology that makes genetic engineering more accessible, affordable, and quite precise.

How CRISPR Works

CRISPR is an acronym for “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats”. It’s an adaptive immune system found in bacteria that targets undesired genome sequences. In the words of the co-discoverer, Professor Jennifer Doudna of Berkeley:

Bacteria have to deal with viruses in their environment, and we can think about a viral infection like a ticking time bomb — a bacterium has only a few minutes to defuse the bomb before it gets destroyed. So, many bacteria have in their cells an adaptive immune system called CRISPR, that allows them to detect viral DNA and destroy it.

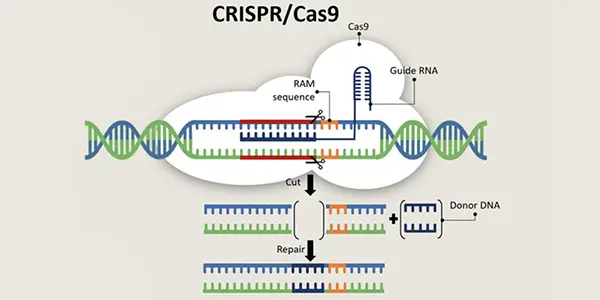

Part of the CRISPR system is a protein called Cas9, that’s able to seek out, cut and eventually degrade viral DNA in a specific way. And it was through our research to understand the activity of this protein, Cas9, that we realized that we could harness its function as a genetic engineering technology — a way for scientists to delete or insert specific bits of DNA into cells with incredible precision — that would offer opportunities to do things that really haven’t been possible in the past.

Essentially, Cas9 identifies the undesired sequence in the DNA, cuts it out, and repairs it by inserting a new sequence. This winning entry for a Freelancer contest by graphic designer, Ga1ina, captures the process pretty well:

Not only does CRISPR give us access to extremely precise genome editing, it’s less expensive than earlier techniques as well. It’s so affordable that DIY CRISPR kits are available for purchase on Amazon. CRISPR has already been looked at for treating things like sickle cell anemia, and may be the tool that brings the extinct woolly mammoth back to life.

It’s a very exciting technology with much promise, but there’s a dark cloud of ethical uncertainty looming ahead: does the future of CRISPR lead to designer babies a la Gattaca?

Designer Babies

Before we address this ethical conundrum, we must first understand the two different types of genetic engineering. Somatic cells are cells like skin, blood, brain — basically any cell that does not involve reproduction. When somatic cells are edited, the edits are not passed on to future generations — they die when the patient dies. However, germline edits involve sperm, eggs, and embryos, which means the edits can affect generations to come. And therein lies the problem. There’s a very fine line between therapy and enhancement when you cross over from somatic to germline editing. Essentially, the evolution of the human race can be steered.

Genome editing using CRISPR has already been done on human embryos, but the embryos were destroyed after experimentation. However, a scientist in China recently claimed to have implanted CRISPR edited embryos, leading to a healthy birth of female twins. This naturally triggered global condemnation, and unfortunately the claims were confirmed to be true by Chinese authorities this past week. A line has been crossed from which we cannot go back.

We are dangerously close to a world in which made-to-order babies are accessible to the rich, thereby widening the divide and discrimination among people with different economic backgrounds. We could trigger a Gattaca-esue world of genetic discrimination, if proper regulations aren’t created and adhered to. Responsibility and ethics are key. I am reminded of this line from Jurassic Park:

Ian Malcolm: [To Hammond] Genetic power is the most awesome force the planet’s ever seen, but you wield it like a kid that’s found his dad’s gun.

It is tempting to say that inherited diseases should all be eradicated, but who gets to decide what qualifies as a genetic flaw that needs fixing? Are things like deafness and blindness flaws? What happens if the technology falls into the wrong hands? Where do we draw the line? There are no solid correct answers to these questions, and so, instead of signing off with questions the way I usually do, I present to you the ending from the original screenplay of Gattaca that never made it to the screen.

More to Explore

Articles

The Quint: China’s Gene-Edited Babies: One Step Closer to ‘Flying Pigs’ (2019)

South China Morning Post: China confirms birth of gene-edited babies, blames scientist He Jiankui for breaking rules (2019)

Business Insider: Bill Gates warns that nobody is paying attention to gene editing, a new technology that could make inequality even worse (2019)

Statnews: Gene drive should be a nonprofit technology (2018)

Mirror: Woolly mammoths could be brought back to LIFE as scientists begin cloning DNA to resurrect the extinct species (2018)

The Atlantic: A Reckless and Needless Use of Gene Editing on Human Embryos (2018)

Reuters: China orders investigation after scientist claims first gene-edited babies (2018)

Inverse: Japan Is Drafting a Rulebook for Ethically Editing the Genes of Human Embryos (2018)

MIT Tech Review: First Gene-Edited Dogs Reported in China (2015)

Videos

Netflix: Designer DNA – Explained

Last Week Tonight: Gene Editing

TED: How CRISPR lets us edit our DNA

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Radha has a PhD in theoretical quantum physics. Apart from research, she consults on sci-fi screenplays/books. In her free time, she cosplays and irritates her three cats. Bug her on Twitter: @RadhaPyari