DYING TO LIVE: The Waiting Game

Alex is a 28 year-old West Australian who has a…

Despite the fact that eight out of ten Australians say they support the idea of organ donation, only 36 percent have registered as donors, an alarming disparity that Richard Todd’s emotionally devastating documentary Dying To Live hopes to change.

This problem isn’t just limited to Australia, America has similar statistics, a 95 percent support rate amongst US adults, compared to the 54 percent that actually sign up. Shot over an intense 3 year period, Todd’s tender follow-up to his controversial feature-length debut Frackman is equal parts heartbreaking and heartwarming, following the lives of 6 everyday Australians as they wait for vital organ donations, capturing the constant anxiety and angst that comes with being on the long waiting list.

Starting With Zaidee’s Story

The film opens with an animated re-enactment of an unspeakable tragedy; In December 2004, at the young age of just 7 years old, Zaidee Turner died suddenly from a cerebral aneurism. Her whole family had previously signed up to become organ and tissue donors, so from one devastating loss, the lives of seven people were saved, a miraculous act that immediately emphasises the benefits of registering to donate.

This prompted her father Alan to start Zaidee’s Rainbow Foundation, an association which aims to promote organ and tissue donation awareness – at the time of her death, Zaidee was the only child under the age of 16 in Victoria to be registered as an organ donor. We first meet Alan as he’s speaking at a benefit for Kate, a 29-year old tattoo model who suffers from PRES Syndrome and has waited several years for a kidney and pancreas transplant. As she points out, it’s not just her that’s waiting on that transplant list, it’s her friends and family who are all kept in limbo, constantly waiting for the one call that could change her life before it’s too late.

From here we meet a collection of people with similar stories from all around Australia; Wood-burning artist Peter “Wood” Woody and 18 month-year old Levi both need kidney transplants (Levi receives one from his parents, the single case of living donors represented in the film), Holly who has lived with cystic fibrosis all of her life, waits for a double lung donation, Tony is a cancer survivor who requires a new liver and then there’s Henry, an elderly Aboriginal painter who lives up in the Kimberly, who wishes for a cornea transplant so he can return to his love of painting.

The film details the stress that comes with the wait, and then the eventual relief for those who finally get the donation they need (unfortunately, 15% of people on the list for an organ donation in Australia die whilst waiting), which brings forth a whole new type of anxiety – the strong possibility of organ rejection.

Touching Tales

Todd and his hard-working camera crew manage to capture every new development, with their intimate access creating an incredible level of empathetic engagement. As the clock ticks on, I found myself constantly hoping for the best – whether it be witnessing their domestic dramas, learning the news about receiving a donation, interviews with the surgeons mid-operation, meeting the recipients post-surgery or even getting to see how the lucky few saved recipients choose to use their new lease on life. The film makes sure to highlight the gentle moments in-between, to help illuminate each of these personalities beyond their health problems.

One particular sequence where we see Kate compete in the Miss Ink Melbourne contest is thoroughly inspiring, displaying both her bravery and resilience during the most difficult time of her life, whilst getting to exhibit her favourite tattoos to an enthusiastic crowd.

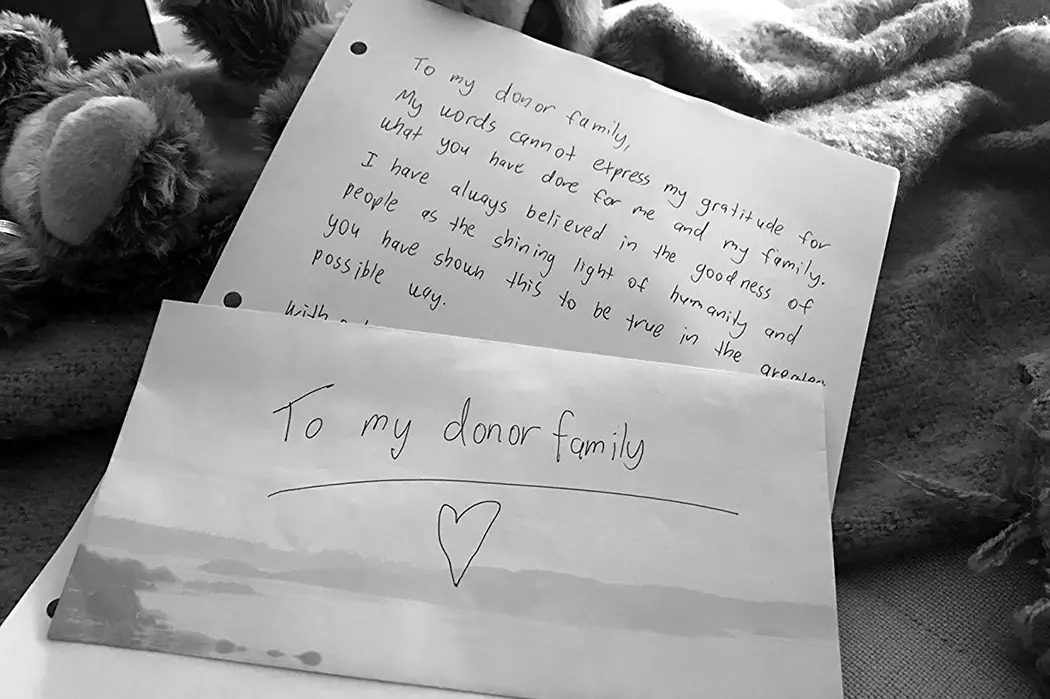

The film can quite confronting too, both in its raw depictions of those who are in need, but also in terms of confronting the audience with their own personal reasons as to why they haven’t signed up to become organ donors, as Dying To Live makes a pretty convincing argument that it’s an incredibly beneficial act of kindness. This sentiment is especially solidified in the film’s magically soul-stirring ending, one which is guaranteed to draw tears of both happiness and sadness from any crowd, as it’s hard not to be touched by the genuine humanity on display.

Todd’s naturalistic cinéma vérité style displays a truthful honesty towards his subjects; it’s obvious behind the camera that he has a readiness to listen and learn from them, capturing each of the different recipient’s subjective visions of the world and what it means to them.

Dying to Live: Conclusion

Richard Todd’s Dying to Live is a sincere portrait of the state of Australian organ donation, a weirdly taboo topic with the highest of stakes. Life and death hang in the balance as people, both the recipients and those around them, wait in suspense for that one call that may change all of their lives.

The sympathetic approach to the often-painful stories is bound to affect any viewer, both young and old, and prompt them to start the chat; because as this film is keenly aware, every social movement starts with a simple conversation, and this time it can begin with this: what’s stopping you from becoming an organ donor?

Dates and Ticket information for upcoming screenings of Dying to Live, as it currently tours Australia, can be found here.

For any Australians interested in becoming organ donors or would like more information regarding #HavetheChat, can register at DonateLife. Americans who are also interested can sign up here.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.