Dancing with Denis Lavant: The 21st Century’s Silent Comedian

23-year-old writer from Newcastle, Australia. Takes some photos too!

For the first class of my degree’s introductory film studies course, our tutor screened, of all things, Holy Motors. He entered the lecture hall, moused through some introductory slides and started the film, leaving us unassuming, would-be media students to grapple with one of the strangest and most divisive films of the 21st century.

It was a bold choice, wringing laughs and squeamish looks from its uninitiated audience. I was later taken on as a student tutor for the course, and I saw the film again with each semester. Holy Motors slowly crept upon me as a favourite, and discussing it with new intakes became a biannual highlight.

Parsing through the bewildering experience, we often agreed on one thing: none of us had quite seen a performance like Denis Lavant’s Mr. Oscar before. Throughout the film, he shape-shifts through almost a dozen discrete roles with an entirely different presence and pathos for each. Having since seen him in many other films, it’s clear to me that he is among today’s most unique onscreen talents; Lavant’s singular ability to express character and emotion physically reads like a modern take on the early silent comedy greats.

Who is Denis Lavant?

Long associated with French arthouse, Denis Lavant first came to notice with his bombastic leading roles in Leos Carax’s equally explosive early films. Having since been poached by filmmaking greats such as Claire Denis and Harmony Korine, his infrequent leading or main-cast roles have become major events in the film world in and of themselves.

With a background in circus, dance and theatre, Lavant‘s roles often put physicality centre stage; whether it’s as a strict, intimidating but emotionally repressed Foreign Legion officer in Beau Travail, a circus performer with a broken leg in Lovers on the Bridge, a literal cave troll (among ten other things) in Holy Motors, or even Charlie Chaplin himself in Mister Lonely. As such, Lavant’s appearances are almost cross-disciplinary, often drawing as much from contemporary dance, theatrical caricature and acrobatics as they might have from today’s film acting naturalism. Lavant has confirmed as much, stating in 2008, over two decades into his film career, that he is, “above all, a theatre artist.“

This is also made apparent by some of Lavant’s notable non-film, or not-quite-film appearances. In the music video for UNKLE’s “Rabbit in Your Headlights” (song featuring Thom Yorke, video directed by Jonathan Glazer!) Lavant‘s featured as a ranting lunatic who obliviously hobbles at speed down a busy tunnel highway; he is repeatedly and comedically hit by cars, limbs splaying out and back in again. Taiwanese auteur Tsai Ming-liang’s 2014 experimental film Journey to the West depicts a Buddhist monk performing the Zen kinhin “walking meditation” practice – walking at a slow, barely perceptible pace through bustling French cityscapes. Halfway through the film, we notice he is being followed by Lavant, who’s tracing the monk’s minuscule movements some meters back.

Despite the obvious disparity between these two examples – slapstick lunacy and glacial stillness – a clear picture emerges: Lavant’s foremost concern in his work, acting or otherwise, is the movement itself, in all its intricacy and possibility.

A Method to the Madness

Lavant is often referred to as a “character actor.” His physical abilities and contortion command of mannerism, posture, and inflection lend well to unusual roles: exuberant weirdos, tortured artists, sewer monsters, and staggering drunks. I think it would be a disservice to paint him as an actor of extremes and nothing else, however; Denis Lavant is as capable with the subtleties of emotion as he is with the madness of movement, and his ability to marry the two and work across their spectrum elevates his performances.

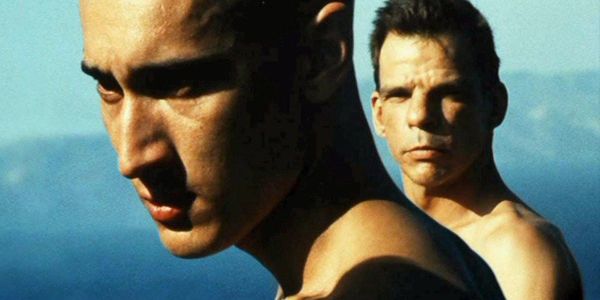

Look no further than Beau Travail, Claire Denis’ masterpiece on colonialism and masculinity in crisis, to see this play out. Lavant stars as Galoup, an orderly Foreign Legion Officer leading a small outcrop of soldiers stationed in distant Djibouti. For the film’s first 90 minutes, Galoup is tense, understated, and conflicted. Aside from its intense military training sequences, we see nothing of Lavant’s signature exuberance. With the introduction of Sentain, a handsome and charismatic new recruit, cracks appear in Galoup’s visage, and eventually, whether, through repressed desire or hateful jealousy, Galoup unfairly punishes Sentain by leaving him stranded in the desert. He is expelled from the Legionnaires as a result.

The film is punctuated by scenes of the soldiers dancing in a Djibouti nightclub, advancing upon the local women in a clear sexual hierarchy. The film’s exalting final minutes stand in stark contrast to all before; we see an expelled Galoup, alone on another dance floor, wearing all black other than his white ballroom shoes. He makes vague trails, odd sways, and flicks in time with the music – “Rhythm of the Night” – as if mustering up courage, testing new waters. Finally, he explodes into movement with a shrieking dance routine, the first fluid then angular, flying through the air and spinning in dazzling, possessed circles. It’s an incredible moment of catharsis and liberation, an exclamation point to Galoup’s repressed military life. No one but Lavant could have pulled it off.

Holy Motors

And then, of course, there’s Holy Motors. Carax’s post-modern mega-farce stands as a signpost of the times, an examination of where cinema has been and all that it can be. The film is interspersed with flashes of the earliest moving images – hands opening and closing, a man smashing a boulder on the ground – as a testament to film’s beginnings as a documentation of movement. Almost every genre and emotion put to film since then is squeezed into Holy Motors. Who better than Denis Lavant to take the helm?

Lavant’s Mr. Oscar is, essentially, an actor. He is delivered, by limousine and driver Celine, to various ‘assignments’, where he performs a moment of someone else’s life before returning to his mobile dressing room to prepare for the next. In one day, Oscar acts out touching, emotive highs – an old man on his deathbed reunites with a distant niece; a father chides his daughter for her shyness at a party he has picked her up from early – and strange, sometimes hideous lows – a gleefully absurd scene in which Mr. Oscar, as a gangster, attempts to murder a spitting lookalike, and it remains uncertain which of the two returns to the limousine; or as a sewer-dwelling goblin who kidnaps a model and bites off the photographer’s fingers.

During my first screening of Holy Motors, I spent a lot of time trying to extract or organize some narrative from it. Is it a reality gameshow? Is Mr. Oscar paid to enact moments from people’s lives that they may not otherwise wish to live through? But why then act as an unnoticed beggar, and what of the magical realism moments – casual resurrections, the fourth wall breaks, and musical numbers? I came to peace with the ambiguity only by returning to Denis Lavant’s performance, which twists and turns with each new assignment, from attentive emotive nuances through to literal acrobatic feats. Again, there’s only Denis Lavant with the range and depth for such a role.

Today’s Silent Comedian

Leos Carax is notoriously unenthusiastic about interviews, often dismissing questions or giving silly non-answers. When asked about Lavant’s leading role for Holy Motors, however, he was more direct: “If Denis had said no, I would have offered the part to Lon Chaney or to Chaplin. Or to Peter Lorre or Michel Simon. All of whom are dead.”

Carax isn’t the only one who sees the similarity between Lavant’s manic on-screen energy and the exaggerated emotions of the early silent comedians listed in his answer. Harmony Korine even cast him as a Charlie Chaplin impersonator in Mister Lonely, where Lavant‘s pitch-perfect Chaplin lives in a Scottish Highlands commune of celebrity impersonators. The comparison is strong, as Lavant’s sense for physical comedy, tragedy, and everything in between is often as sharp as those of the early 20th-century greats, though transposed to complex emotional landscapes of today.

Case in point would be Lavant as Alex, a broken-footed, homeless, addict circus performer in Lovers on the Bridge. Alongside Juliette Binoche’s equally great performance as the also homeless, lovesick, slowly-going-blind painter Michele, Lovers on the Bridge is a heightened, fantastical look at crazy, doomed love. Such ridiculous, adjective-heavy character descriptions would become clumsy in most actors’ hands, but Lavant’s deft turns of emotion and physicality keep perfect time with the film’s manic pace – from the joy of new love, which has him literally climbing walls, through the drunken despair of betrayal, which sees him stagger across the Pont-Neuf Bridge, bottle in one hand and crutch the other.

There is a unique joy of movement in Denis Lavant‘s work that is rare to see elsewhere. In recent decades, the range of on-screen expression has slowly shrunk into various shades of lifelike naturalism (obviously, there are plenty of exceptions, and this isn’t inherently a bad thing). Lavant‘s bold exaggerations and emotion-through-movement offer both a breath of fresh air and a distinct call-back to the early greats.

Do you know any other actors with uniquely physical, movement-based performances? Is there anyone else you’d consider a “21st-century silent comedian?” Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.