Remembering Something That Never Was: Dementia & the Horror Genre

Blake I. Collier hails from the flatlands of the Texas…

“Get your pitchforks out

The crowd is coming and they’ve named you

You open up your mouth

You find your language it has escaped you

And it’s too bad

You’re gonna need it now

There’s no system left to save you”—”Unusual” by Typhoon

My father currently haunts the quadrants of his memory facility. Head down, back slightly hunched, and scabbed from previous falls, he stalks the corridors of the building. The nurses, janitors, maintenance, and cooks love his generally congenial presence amongst the other residents who suffer from dementia and Alzheimer’s like my father. He was 58 when he was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s—something that has been discovered in people as early as infancy which seemingly correlates with amounts of air pollution, among other factors. He was doomed to become one number among the 13.8 million Americans that will be diagnosed by 2050.

My father is barely verbal. If he does speak, he does so with only the outer edges of words and repetitive sounds. Sometimes he’ll eat on his own, but often he must be fed or coaxed to eat. He and the other residents of the facility gaze upon the new, same faces every morning. The terror of Alzheimer’s and dementia is the isolating effect it has on its victims. Relationships and the metaphysical grasp on reality they once had is shattered because the linguistic symbols are divorced from their correlative meanings. Their internal Towers of Babel are toppled and their language is confusing. They don’t know their loved ones and they don’t know themselves.

The Blank Slate

When horror takes on such subject matter, it must walk a tight rope, especially in this day and age. Within the echo chambers of social media and the threat of social cancellation, care and attention are needed. However, our society is such that we turn a blind eye to any systemic issues until they become a threat to us. #MeToo and Black Lives Matter came into national consciousness because of increased reporting on famous cases of sexual harassment (and perhaps the occasional non-famous case) and the viral videos of black men and women being killed by police. In the midst of the vocal and physical protest, these movements became threatening to the powers that be. They demanded to be heard.

This is not the case with Alzheimer’s and dementia, because it largely affects the elderly and our society hasn’t had the best track record in caring for the old, or veterans, or, really, anyone. This specific threat, however, is nearing a precipice in the coming years when it will become a significant public health crisis. Yet those who would best be able to start a movement for better healthcare and representation can barely say their names if they can talk at all. In the rare moments when horror utilizes dementia (or really any forms of mental and cognitive impairments), it runs the risk of exploiting a still largely invisible population of people who suffer daily along with their loved ones.

The two main films that corner the market on dementia horror and remain the most critically noted are 2014’s The Taking of Deborah Logan and this year’s Relic. There are few other films that explicitly devote their narratives to dementia horror. 2015’s Dementia plays out more like a Hitchc*ckian thriller than a horror film and its usage of dementia is largely sidelined by the intrigue of the cat-and-mouse game. However, it isn’t devoid of commentary on the nature of memory loss. 2008’s Pontypool, while not explicitly dealing with dementia, strikes a philosophical and emotional chord with, specifically, Alzheimer’s deconstruction of language and what is called “semantic satiation”—the linguistic phenomenon when a word is repeated so often in a short period of time that it temporarily loses its meaning in the mind of the speaker.

The subject of dementia and Alzheimer’s, however, has wider representation in the drama genre. Such films as Still Alice (2014), What They Had (2018), The Leisure Seeker (2017), and Robot & Frank (2012) dealt with the emotional tolls that dementia wreaks on those who suffer from it and the residual effects of it within their families. All of these dramatic narratives have the existential horror that is inherent in placing oneself in the shoes of someone with the disease for a couple of hours. Yet the point of these films is to create an emotional connection and not to terrify their audiences.

In many ways, dementia horror remains a blank cinematic slate. If the culture ever starts to get in tune with the growing numbers of Alzheimer’s patients, then depictions and representations on-screen will hopefully increase along with general awareness of this insidious disease. Yet, as we have learned in the past several years, it’s not just representation that matters, but the type of representation that becomes prevalent. This is where the distinction between exploitation and, what I’m going to call, accentuation is so important within, specifically, horror cinema.

The Devil Lies In Our Minds

The Taking of Deborah Logan is essentially a found-footage, documentary-style horror film that follows a trio of student filmmakers as they chronicle the day-to-day life of Deborah Logan (Jill Larson), who has Alzheimer’s disease, and her daughter, Sarah (Anne Ramsay). The time at their largely rural estate starts off normally as we become witnesses to some of the more trademark symptoms and deteriorations of the disease. Deborah forgets where she is, she wanders off, and she finds herself panicking and striking out in anger in the midst of her memory loss.

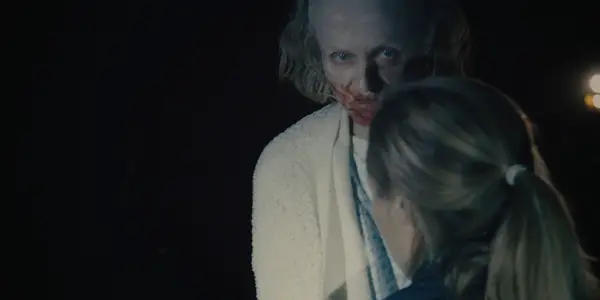

As the film goes on, her behavior becomes more erratic, eerier, as she stands in the hallway watching the cameraman install a cam in the house hallway. He doesn’t know she is there until she walks into another room and slams the door. The young filmmakers get overnight footage that shows Deborah in the kitchen and records her jumping from the floor to the kitchen countertop in a split second with no editing on the timestamp. There is an iconic scene where the sound of an old phone ring is heard throughout the house and they find Deborah up in the attic, naked, attending to the old phone operator unit she used in her earlier days. The unit hadn’t worked in years. It becomes clear that Deborah’s behavior is not merely Alzheimer’s, but something evil and demonic in nature.

From that point on, the film falls into the typical tropes of found footage films and stops really caring at all about the dementia storyline. They just needed a gimmick to get to the onslaught of jump scares. By the end, the film is more concerned with the exorcism of Deborah’s demon than it is about the initial concern for her mental and physical well-being.

There is an ongoing argumentation within American Evangelical circles that equates mental health and cognitive impairments with sin and the evils that we allow in. In my younger days, I am ashamed to say that in my brash Evangelical faith, I, too, made the case that mental health was nothing more than unaddressed sin in the person’s life. Thankfully, I’ve moved away from that erroneous thinking. Yet, I can’t help but think back to that argumentation in the times I have watched The Taking of Deborah Logan. If one looks at the narrative flow of the film, it is essentially making the case that mental illness and cognitive diseases are nothing more than demonic possession which should, therefore, be extinguished. The unsaid presumption behind this logical inclination is that the person suffering somehow invited this evil in themselves.

This form of argument is not only atrocious Christian theology, but it minimizes the real suffering of an increasing number of people throughout the world. The Taking of Deborah Logan, intentionally or not, ends up exploiting a horrid disease for thrills and scares and ultimately shifts the focus from Alzheimer’s and its inherent terrors to typical horror clichés. And, worst of all, it ultimately demonizes the sufferer.

Who We Will Become Haunts Us Now

Those people who have watched and enjoyed The Taking of Deborah Logan probably have some level of detachment from people who have suffered from Alzheimer’s and I can’t honestly blame them. The film came out pretty close to my father’s diagnosis and so it was fresh on my mind. I didn’t like what I saw and when I revisited it recently after having viewed Relic (2020) for the first time, its failures were only made more visible. Relic is an example of what it means to depict those who suffer from dementia and Alzheimer’s without demonizing them or exploiting their suffering for thrills and profit.

It is no surprise then that Relic‘s director, Natalie Erika James, wrote the film based on her experience of watching her grandmother succumb to Alzheimer’s:

It came from a really personal place. My grandmother, who lived in Japan, had Alzheimer’s and I had taken a trip to go see her. She’d suffered from Alzheimer’s for some time and it was quite a slow decline, but that particular trip was the first time she couldn’t remember who I was. And it really had a deep impact on me because it’s obviously heartbreaking when someone who’s only ever looked at you with love is looking at you like a stranger. I felt a lot of guilt and regret at not having gone to see her more often.

Her sentiments are things I have felt myself in the wake of watching my father deteriorate physically and mentally. I beat myself up for all the petty gripes I had with him, all the times I didn’t take to show him that I loved him, and every moment I had with him that I ultimately wasted not being present. It is something that follows everyone who’s loved one is suffering from it. My father is no longer my father, but he is still someone who must be loved and cared for even if he is no longer recognizable outside of physical appearance. My mother’s struggles with being his main caretaker and learning to live life largely apart from him, now, is even more agonizing than my own feelings towards him.

Relic succeeds because it understands the fragility of the remaining connections between the sufferer and their family. It seeks to accentuate the horror of dementia and Alzheimer’s without demonizing or exploiting that specific suffering. James’ eye never veers away from examining the havoc of the disease on the person affected and how that fear (not to mention the potential genetic inheritance) of the disease changes those who are bound by those relationships.

Relic focuses in on three generations of women: Edna (Robyn Nevin), the matriarch who has Alzheimer’s, Kay (Emily Mortimer), Edna’s daughter, and Sam (Bella Heathcote), Kay’s daughter. Edna wanders off from her house one night and no one can find her, so Kay and Sam drive to her residence to join search teams looking for her. Edna arrives back at her house randomly one morning, but something about her is different. In a similar way, Relic echoes the early beats of The Taking of Deborah Logan by showing her absentmindedness, her lashing out in anger, and her inability to recall names and other aspects of her short-term memory.

Yet, this is all the films share in common. Relic instead ratchets up the dread and tension of Kay and Sam’s realization and recognition of their matriarch’s disease where The Taking of Deborah Logan chose to detach its viewers from the inherent suffering more than they probably already were. James, instead, enters into that suffering, giving her audience a piece of what it means to live life with a person who is becoming someone new, someone, alien, someone diminished from who they once were. This new person is portrayed as a shadowy figure that lives in the house and can mostly be seen in the darkened corners of Edna’s house. This apparition is who Edna is to become, we and her daughter and granddaughter just don’t know it yet.

There are a couple of moments at the end of the film that exemplifies the care taken to accentuate, not exploit, the horrors of Alzheimer’s. The conclusion of the film incarnates near perfectly the emotions that those of us who have traveled down this road have felt on that journey. The horror of seeing that which our parent, sibling, significant other are becoming and the eventual acceptance of this new person, no matter how decrepit and alien they have or may become. Yet instead of allowing the audience to detach themselves from this specific suffering, the film chooses to bring its audience into the embrace of that suffering. To find mercy and a new love for someone familiar, but altogether new.

The final scene of the three generations of women together in their new reality is simultaneously haunting and hopeful. Instead of demonizing this new person, they draw near to her and identify with her to the point that the final reveal echoes a reality that every child who has walked alongside their parent wonder about in the back of their heads. I know that I definitely do.

Moving Toward The Future In Light Of The Past

There is a lot of room for film to explore the ravages of dementia, especially within the horror genre. However, my hope for the future of dementia horror is one that takes account of the fragility of the disease and the largely invisible nature of their suffering. When the culture doesn’t have their sights set on a specific cause, then poor representation and unintended (or intended) minimizing take place without corrective. As the numbers of people in this country—let alone the world—who are given this diagnosis increase, may their stories increase within popular culture and film, for the sake of awareness, but also understanding.

I hope Hollywood chooses to follow the path of Relic rather than The Taking of Deborah Logan and that they find filmmakers who have experienced this horrid disease on a personal level. No one who has experienced it would minimize or demonize their suffering, because, as our loved ones change, we, too, change. The explorations of the subject don’t have to be depictions of the disease either. There is a lot of fertile ground for more abstract art to be done. Like I mentioned earlier, Pontypool remains one of the most important films for me in empathizing with my father. It helps me see what it would be like to communicate via broken words and sounds. Dementia gives a fullness of character to the person suffering, they aren’t always good people, but they are human and no one deserves to suffer from this disease.

Relic embodies the emotional core of watching the deterioration and finding love and acceptance of this new person that we barely know. Where The Taking of Deborah Logan makes us afraid of and despise the sufferer, Relic teaches us how to enter into the suffering and love who the sufferer is becoming no matter how terrifying that might be.

What do you think of the portrayal of dementia if? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Blake I. Collier hails from the flatlands of the Texas Panhandle, but currently resides in Tulsa, Oklahoma with his wife and son. He draws lines (and the occasional circle) for his day job. He has written for various websites mostly about horror and film, but occasionally about the other various facets of existence. He is co-host of So Grosse Such Pointe Much Blank, a podcast focusing specifically on the 1997 film, Grosse Pointe Blank. He, also, has a chapter on QAnon and the 2008 film, Martyrs, in Toxic Cultures: A Companion from Peter Lang Publishing. You can reach him at [email protected].