The fifth feature film from legendary Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr, Damnation chronicles the sad stasis of a depressed alcoholic who is obsessively in love with the married singer at one of his favorite watering holes. First released in 1988, a new 4K restoration from the film’s original 35mm camera negative debuted as part of the Revivals section at the 2020 New York Film Festival and will soon be screened in virtual cinemas across the United States. And while Damnation won’t provide the escapist entertainment that many today are hungry for, it does give us a bleak but beautiful glimpse behind the Iron Curtain, courtesy of a deeply poetic script and some of the most gorgeous black and white cinematography you will ever see.

Stuck in the Mud

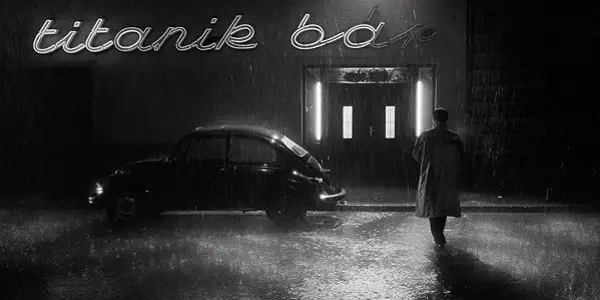

Karrer (Miklós B. Székely) wakes up every day in the shadow of the mining carts that clank back and forth in a seemingly endless cycle above the decrepit village in which he lives. He spends his life meandering from one rundown bar to another while espousing his thoughts and opinions to a series of people who have heard it all before. At one of his favorite spots, Titanik, there is a singer (Vali Kerekes) with whom he is currently involved; however, she is unfortunately married — and has told Karrer that she wants to end their affair.

The elderly coat room attendant at Titanik warns Karrer to stay away from the singer, telling him, “That woman’s a leech. She’s a bottomless swamp, who swallows you up and sucks you in.” But Karrer is unwilling — or, more accurately, unable — to hear her. Madly in love and desperate to get the singer’s debt-saddled husband (György Cserhalmi) out of the way, Karrer sets him up with a smuggling job that was brought to him by the bartender at Titanik. While the husband is away on this mission, Karrer tries to convince the singer to abandon her marriage, telling her, “If I were to lose you, it would be the unforgivable end of me.” Alas, like so many of the best-laid plans, things seem destined for failure from the start.

Hungarian Noir

On the surface, the plot of Damnation could almost belong to a traditional Hollywood noir: ragged antihero falls in love with a married woman and must get rid of her husband by any means, including criminal. But Tarr scrapes every last bit of cinematic gloss from those tropes, forcing us to look beneath the glamour peddled by classic Hollywood at the real, unvarnished people entangled in this so-called love triangle. Indeed, when Tarr gives us a sex scene between his supposedly star-crossed lovers, it lacks the steaminess one would expect from an extramarital affair; instead, it ends up being one of the least erotic and most emotionless sex scenes in cinema.

As Karrer, Miklós B. Székely has one of those wonderfully unpolished faces that, when you look at him, you instantly feel that he has seen what the world has to offer and found it not to be of his liking; his experiences are etched on his skin, impossible to wash away. Meanwhile, as the singer, Vali Kerekes is grungier and more rundown than your typical movie torch singer; when she sings, she is practically doubled over in exhaustion, and her lyrical stylings are closer to spoken word. Yet in her scenes with Karrer, you can understand why he is so set on not giving her up; in a town that seems on the verge of death, she at least contains some spark of life.

The script for Damnation marked the first of many collaborations between Tarr and writer László Krasznahorkai, whose novel Sátántangó formed the basis for the epic drama for which Tarr is probably best known. Their philosophical dialogue above love and life, and the meaning the former can give to the latter when it feels that you have nothing else worth living for, stands in elegant contrast with the often brutish behavior of the humans speaking it. At the same time, there are long stretches of Damnation where there is no dialogue at all, including the opening scene, a shot that lasts for several minutes as the camera slowly and gracefully pulls away from the endless circuit of the mining carts through the bedroom window of Karrer, who stands at the mirror shaving his haggard face.

The almost hypnotic movement of the camera highlights the stasis that the majority of the film’s characters find themselves in, trapped in a dead-end town and dead-end relationships without any means of escape. They’re stuck in a loop, just like those ever-present mining carts, whose almost ominous clanking is as much a part of the film’s soundtrack as Mihály Vig’s minimalist music. Such long, wordless shots, crafted in a pristine black and white that in its shadows almost shimmers silver, form the bulk of Damnation, and their beauty is what helps the film maintain its appeal even as the storyline becomes more and more of a downer.

Damnation is the exact opposite of a mood boost, but when you’re watching the camera slide smoothly through sheets of pouring rain on the almost abandoned streets of the town or hover at a distance above a circle of dancers in a bar that resembles an ouroboros, it’s hard to not feel your spirits lift. Even the ever-present mud that seems to bog down all of the characters both physically and spiritually feels strangely beautiful. Simply put, cinematographer Gábor Medvigy’s work is masterful, and as perfect a fit for the subject matter as one will ever see in the movies. If you watch the restored Damnation for no other reason, let it be that.

Conclusion

If you’re looking to wallow in despair, rather than escape it, then Damnation is the film for you.

What do you think? Are you familiar with the films of Béla Tarr? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

The 4K restoration of Damnation begins screening in virtual cinemas in the U.S. on October 30, 2020. You can find a list of locations here.

Watch Damnation

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.