So-Bad-It’s-Better-Than-Mediocre: On The Craft & Language Of Trash Films

Hazem Fahmy is a poet and critic from Cairo. He…

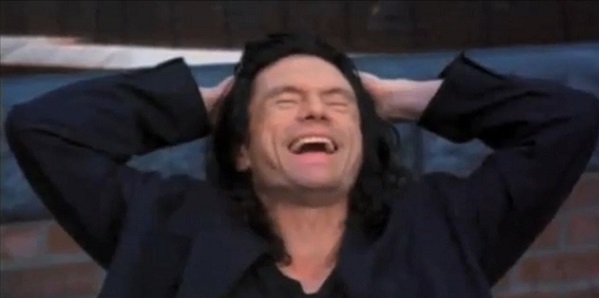

In a recent Vox video essay, Dean Peterson interrogates the popularity of Tommy Wiseau’s legendary cult classic, The Room. Interspersed with commentary by Tom Bissell, the co-author of The Disaster Artist, Greg Sestero’s memoir of his experience as a friend and co-star of Wiseau, the video attempts to answer a question that’s almost as old as feature filmmaking: why do ‘objectively bad’ films often develop very serious, very widespread popularity? If films like The Room and Birdemic are such ‘trash’, why have they endured in the hearts and minds of so many people?

‘Good’ Taste of ‘Bad’ Taste

For Peterson and Bissell, the answer lies in audiences’ propensity to ironically appreciate works of art that completely fail at embodying the aesthetic norms of their mediums. They see the popularity of The Room, and similar films, in tandem with the popularity of camp and paracinema, an academic term that refers to essentially any film product outside of the mainstream industry. Quoting Susan Sontag’s famous essay, Notes on Camp, they reaffirm the notion that: “Camp asserts that good taste is not simply good taste; that there exists, indeed, a good taste of bad taste.”

While I fully agree with their analysis, I think it’s limited, as are many of the conversations critics and fans often have about ‘trash films’. As Sontag points out, there is most certainly an element of cultural and social capital to be had in the ironic appreciation of ‘bad’ movies. If you’re a member of the Manos: The Hands of Fate cult following, there’s immense pleasure to be had in encountering fellow fans of the 1966 classic, and often even more pleasure in luring folks who’ve yet to see it to a screening. But this still begs the question: why do certain ‘bad’ films achieve a cult status while most simply slip into obscurity? If appreciating ‘bad’ films is still a matter of ‘taste’ does that mean there also exists criteria for measuring how ‘good’ a ‘bad’ film is?

I firmly believe there is. I’ve never been comfortable with the ‘so-bad-it’s-good’ label. I find it at best incomplete and at worst simply paradoxical. ‘Bad’ movies that rise to prominent cult status, often leaving an impact on film culture, do so because they are memorable and they are memorable because they, as texts, sustain a consistent aesthetic language and identity. In the aforementioned video, Bissell describes The Room’s aesthetic as: “like a movie made by an alien who has never seen a movie, but has had movies thoroughly explained to him.” Though exceptionally accurate for The Room, this statement is applicable to a large number of cult classics and B-movies, and it explains why, I dare say, they work.

It is true that popular trash films are usually detached from objective and traditional standards of filmmaking, but that in itself is not what makes them so endearingly watchable. Rather, it is the consistency of their detachment, across all facets of the craft, that gives them their genuine appeal. In steering so far off course from what we expect of a film, these works become something entirely unique and, arguably, incomparable to mainstream filmmaking.

In a 2013 essay in The Atlantic, Adam Rosen proposed drew a strong comparison between trash filmmakers (like Wiseau and Ed Wood) and Outsider Artists, a term commonly used to denote visual artists whose work has little to no connection to the mainstream art world, but may still deserve merit and scrutiny. These films are so distant from anything that resembles mainstream filmmaking, it should seem odd that we would label them as ‘failures’ by comparing them to the standards and techniques of mainstream filmmaking.

Kill the Director

Of course, one could cite the author’s intention as a basis for these films’ ‘failure’. After all, Wiseau was dead-set on crafting a moving dark, romantic drama. When he’d conceived of Birdemic: Shock and Terror, James Nguyen genuinely set out to craft a serious homage to Hitchc*ck’s The Birds. Joel Schumacher never intended for Batman & Robin to be perceived as a parody of the franchise he was trusted with. But criticism is long gone passed the tyranny of authorial intent as a measure of a work of art. If each of these films present a cohesively anti-mainstream vision, one that is consistent in its defiance of our expectations, why do we continue to evaluate them based off of the very standards they so viscerally defy?

When I first saw The Room, I was struck by how immaculately every ‘bad’ thing fits with the other. Evaluated separately, every element of the film is an absolute disaster, but together they create a fascinating approach to telling the story of what would otherwise be a trite and forgettable love triangle. Such odd, illogical lines could only have been uttered that coldly and distantly. The choppy editing, epitomized in such non sequitur shots as those infamous ones of the Golden Gate Bridge, only heighten the haphazard plot pacing. Even the bizarre art direction, from hair styling and costuming to décor, seems to serve a purpose, emphasizing how absurd it is that someone like Johnny, with his ill-kempt hair, ostensibly thrifted clothing and collection of framed spoon photographs, is a big shot at a bank. There is no single element of Wiseau’s filmmaking that stands out on its own from the rest, rather they all work with each other to deliver a uniformly whacky vision of love and betrayal.

This level of consistency can also be found in Joel Schumacher’s wildly underrated Batman & Robin. Though its studio budget and position as the fourth installment in a tremendously successful franchise set it apart from the low-budget and amateur quality of the average ‘so-bad-it’s-good-film’, it nonetheless is as persistent in its complete disregard for the established aesthetics of 90’s action blockbusters. Every character delivers their decadently cheesy dialogue in an earnest, over-the-top fashion.

Though the film’s predecessors in the franchise, both of Tim Burton’s and Schumacher’s Batman Forever, were by no means short on camp, Batman & Robin completely committed to the aesthetic. Its Gotham looks like a dystopian neon play set, rife with impossible architecture and colorful gangs with decked out, unique uniforms. Of course, none of that was exactly in demand in the late 90’s, and in that sense, it was a failure, especially given the fact that it cost more than Batman Forever, but ultimately made less. Yet, who really remembers the latter? We can mock Schwarzenegger’s Mr. Freeze all we want, at the end of the day, his are the lines we quote, not Tommy Lee Jones’s Two-Face and certainly not Jim Carrey’s Riddler.

This disparity in memorability between Batman & Robin and Batman Forever, an ‘objectively better’ film, highlights Sontag’s assertion that: “that there exists, indeed, a good taste of bad taste.” This is why ‘solid’, competently made mediocre films practically never become cult classics, or any sort of classic for that matter. Moreover, it’s not enough for a film to be a ‘disaster’ for it to develop a following or just be memorable, it has to be a comprehensive ‘disaster’ that is so distant from our traditional standards that it becomes its own thing, incapable of fair comparison to the mainstream.

Consider David Ayer’s Suicide Squad or Neill Blomkamp’s CHAPPiE, both widely considered to be among the worst films of the decade. The only kind of dialogue either has generated has revolved solely around how bitterly disappointing each was to fans of DC and Blomkamp respectively. In other words, they’re only remembered for what they could have been, not what they are, and this brings us back again to the issue of consistency.

Suicide Squad actively attempted to adhere to what we expect out of a good comic book movie, and it lays a lot of the groundwork for just that. CHAPPiE does have some strong elements of good science fiction in its narrative. And that’s exactly why these films ‘failed’. As viewers, we can see the polished stories they were trying to be, so we’re left with a much more potent sense of disappointment, whereas The Room or Batman & Robin are so far off the mark that we can only see them for what they are. That’s why they’re the ‘good’ kind of ‘bad’.

Conclusion

It’s interesting that Jim Sharman’s The Rocky Horror Picture Show, the undisputed king midnight cult movies, seems to have evaded the classification of ‘so-bad-it’s-good’ even though it was also widely panned and dismissed upon initial release for its plotting, scripting and editing among other things. This has drastically changed over time, however. Besides being generally held favorably among contemporary critics, the film is also commonly subject to serious analysis for its influence on pop and queer culture, even though it was widely panned and dismissed upon release back in 1975. In addition to the feverish quality of its cult following, I believe the film has managed to earn this respected position in film history through its explicit homage to earlier B-movie horror and science fiction cinema.

Richard O’Brien, the writer of the original stage musical from which the film is adapted, grew up on these films and wanted to make a work that would draw from their rich canon. Add a dash of Steve Reeves muscle flicks as well as 50’s rock n’ roll and you get the will pastiche of influence that made up Rocky Horror. In that light, it makes perfect sense why the film is written, paced and cut like it is. From the get-go, vis-à-vis the mesmerizing tune of ‘Science Fiction/Double Feature’, Sharman establishes that this is a film that is in direct conversation with the giants of B-movie cinema, so the audience receives concrete context as to what the hell is going on.

But we shouldn’t celebrate Rocky Horror fascinating and dynamic cultural collage simply because we know the creators’ intentions in retrospect, rather we should celebrate it because it speaks for itself and, over forty years later, still delivers a truly bold and unique vision. So if authorial intention shouldn’t matter, and we can accept aesthetic subversion as a form of commentary or aesthetic in and of itself, why do we still consider trash films as some sort of failures? Can’t The Room be read as a scathing mockery of the American Dream, embodied in the hardworking, but inevitably doomed Johnny? Is Batman & Robin not an ode to the glory days of Batman camp, one that also allows itself to be freer and more honest about the innate sexuality of the character? I’m not entirely sure they are, but I know they could be.

What are your favorite trash films?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Hazem Fahmy is a poet and critic from Cairo. He is an Honors graduate of Wesleyan University’s College of Letters where he studied literature, philosophy, history and film. His work has appeared, or is forthcoming in Apogee, HEArt, Mizna, and The Offing. In his spare time, Hazem writes about the Middle East and tries to come up with creative ways to mock Classicism. He makes videos occasionally.