CPH:DOX 2020: SONGS OF REPRESSION, CAUGHT IN THE NET & More

Musanna Ahmed is a freelance film critic writing for Film…

The whole world is in disarray at the moment and the ban on public gatherings has seen the postponement or cancellation of film festivals around the world, from SXSW to Cannes. The festival organisers of CPH:DOX, Copenhagen’s international documentary festival, one of the largest in the world for docs, deserve applause for finding a solution at the most uncertain period of the global coronavirus outbreak by fully digitizing the festival.

2020’s edition was able to go ahead online with viewers in Denmark able to view films for just €6 and tune in to live-streamed events for free (all available on YouTube), including a talk with Edward Snowden. As usual, the selection was vast and varied, from strong social issue films (The Fight for Greenland, I Am Not Alone) to dazzling impressionistic features (Ecstasy, I Walk On Water), highlights from previous festivals (The Kingmaker, Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets) and biopics on icons including Charles Aznavour, Margaret Atwood and Andrei Tarkovsky. I had the privilege of virtually attending CPH:DOX 2020 to write about what I saw.

Here are reviews of five films, including the aforementioned Tarkovsky biopic and the main competition winner Songs of Repression.

Andrey Tarkovsky. A Cinema Prayer (Andrey A. Tarkovskiy)

There’s a certain style of posthumous biographical documentary filmmaking afforded only to iconic cultural figures such as Marlon Brando (Listen to Me Marlon), Fred Rogers (Won’t You Be My Neighbor?) and Tupac (Tupac: Resurrection), who had such a big imprint in the culture. This particular style is composed of entire archive footage narrated only by the late subject themselves, the bits and bobs of their stories extracted from a variety of sources throughout their storied career.

Andrey Tarkovsky, one of the greatest filmmakers in history, gets the same treatment in this film directed by his son Andrei A. Tarkovskiy, who should be commended for utilising this format when he had all the tools to make a more traditional tribute to his old man. Andrey Tarkovsky: A Cinema Prayer is a wonderful service in the church of art. We listen to Tarkovsky recount the production and reception of his masterful filmography and his thoughts on the intersection of religion, culture and cinema, as well as key details in his life such as the guidance of his parents through his youth during wartime.

Andrey’s own father, Arseny, is a major part of the film. Arseny was an esteemed poet and this film gives us the opportunity to listen to him recite his poems, never heard before. Tarkovskiy skillfully assembles the vocal extracts and scenes from his father’s work, including behind-the-scenes footage of Tarkovsky directing Stalker, Andrei Rublev and his sole play Hamlet, whilst maintaining the hypnotic, serene aesthetic that characterised his father’s films.

More than just a warm remembrance of the great films that he made, this documentary serves as a strong conversation starter for fans to discuss the points Tarkovsky made, whether they be his thoughts on spirituality, his stance on the development of the auteur theory, or even his overly critical reflection on the success of his debut feature Ivan’s Childhood. Of course, this documentary is a must-see for Tarkovsky’s devotees but it’s a must-see for cinephiles in general.

Caught in the Net (Barbora Chalupová & Vít Klusák)

This might be the most disturbing, uncomfortable, sickening documentary film I’ve ever seen. I could continue with the synonyms but there aren’t enough to describe how awfully widespread is the epidemic of online child abuse, as depicted here. Caught in the Net is a Czechoslovakian structured documentary centred on an experiment devised by directing duo Barbora Chalupová and Vít Klusák, who want to investigate the world of online child sexual abuse. Their experimental project takes three baby-faced adult-age actresses, attires them in pre-teen wear and places them into makeshift bedrooms in a single film studio.

Social media accounts are made for them on Facebook, Skype and Lide.cz, a live chatting service similar to Omegle. Following a strict code of conduct, the actresses are directed to act as 12-year-old girls and talk to strangers across the web whilst the directors sit psychologists, lawyers and other experts across the film studio and examine how easily young girls are being exploited online by predatory adults.

For a film where you want to look away from the screen almost the whole time, Caught in the Net is impossibly gripping. It documents the text and video-based conversations between the actresses and the endless amount of predators they encounter, who have their faces censored in such a way that they can still be identified – a great trick for any Czech viewers to identify them as possibly someone they know and must report.

Much of the film depicts the chilling Skype conversations where men sexually harass the girls, try to coerce them for nude images and repeatedly affirm that they don’t mind that the girls are 12. The repetitive nature of these conversations – the quantity of which destroys any faith in humanity – captures just how wide-spanning the problem is, how many children are at risk online, and how little moderation there is on the internet to mitigate it all.

The shooting style is quite dynamic, switching from digital interfaces to live reactions in the studio from the actresses and their observers, but there’s only so many conversations between creepy men and young girls one can stomach before wanting to turn the film off – or worse, lapse into numbness. Mercifully, though, at some point the observational piece transmogrifies into a straight-up social intervention, To Catch a Predator-style, with the crew agreeing to fulfill the requests of several predators who want to meet face-to-face over coffee. Secret cameras and strategically placed bodyguards keep our heart rates in check as the potential for horror grows in parallel to the chance of vigilantism.

It’s extremely sad that nothing seems to be done to eliminate this problem but I applaud these filmmakers for what they achieved here by tactically capturing the worst of the worst – we’re informed in the closing credits that the materials have been handed to the police and I’m positive that this footage could lead to a number of arrests. Certainly, there already are statistics to tell us how bad things are online but such an experiment gives the directors a chance to confront the problem head-on.

There are some unexpected surprises in the film, not least of them being a dose of extreme gallows humour like when a stray dog walks towards a seated pervert, who’s in the middle of pressuring of the girls to go home with him, and pisses by his feet. Thank you, dog.

Songs of Repression (Estephan Wagner & Marianne Hougen-Moraga)

When I sat stunned at the end of watching Songs of Repression, I was not surprised to see Joshua Oppenheimer’s name in the credits as an executive producer. This momentous documentary, co-directed by Estephan Wagner and Marianne Hougen-Moraga, is akin to films such as Oppenheimer’s The Look of Silence and Spanish doc The Silence of Others in how it remarkably creates space for victims to open up about long-repressed memories.

The title of this film is a clever description of the tradition that binds the past and present together in this portrait of a German colony in Chile. It was back in 1961 when a group of Germans, led by the infamous Paul Schäfer, formed an isolated religious community in Chile called the “colony of dignity.” All members spied on each other and they collaborated with Pinochet’s regime to torture political prisoners.

The colony was the basis for a forgotten Emma Watson thriller – imaginatively titled The Colony – which buckled under Hollywoodization of the subject matter, resulting in something too hackneyed as entertainment and, as history, too ignorant of the issues at heart. However, some of the presentations in the film were spot on – brutal group meetings were everyday practise, there was strict gender segregation, and the children were separated from their parents and systemically sexually abused.

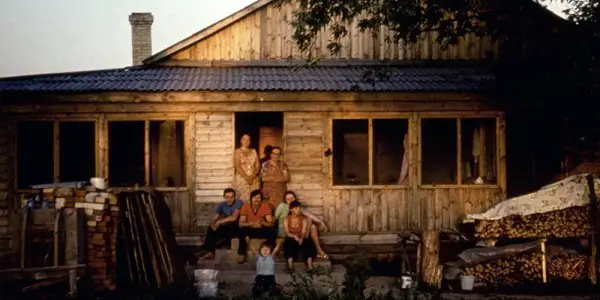

Songs of Repression takes us to the community today where there are still around 120 people living there, many of whom were once those kids. Those children are now adults living under a “forgive and forget” pact whilst Schäfer’s living colleagues (fellow abusers) are frail and in nursing homes. The leader himself is gone, having died in jail in 2010 following an arrest in the mid-’00s. Men, women and children co-exist now, and choir sessions continue. For many, the folk songs from their youth are a bonding experience but, for others, it’s too difficult to participate. Therefore, songs of repression is an apt descriptor.

The film unfolds with great sensitivity and nuance, capturing the many subjects in their day-to-day lives and steadily providing them with the time and space to discuss the abuse that took place all those decades ago. Naturally, it’s extremely difficult for the subjects to open up but, once they do, there’s a clear consensus on how evil this cult was and how religion was used as a tool of control for the residents. They couldn’t even recognise the lifestyle as cruel.

In addition to their superb interpersonal abilities to carefully acquire insight and openness from their subjects, where Wagner and Hougen-Moraga really achieve in making the most powerful and tactful film that their subjects deserve is in the craft. They’re always moving their lens towards faces and hands to identify the subtle body language when conducting talking heads rather than probing any subject to talk, especially those who visibly break when recalling such a traumatising time period.

They don’t employ a score, keeping things raw and avoiding sensationalism, and they let their shots breathe in the edit, thoughtfully showing how the subjects process themselves before and after the heavy discussions. To have earned the trust of this community for a documentary film was significant enough, and the finished result proves to be really important. Simply put, Songs of Repression is one of the most compelling documentaries of the year. One hopes the subjects have found peace in being able to share their stories after living under the umbrella of “forgive and forget”.

American Rapstar (Justin Staple)

Hip-hop recently saw the rise and decline of a trend dubbed “SoundCloud rap”, synonymous with “emo rap” and “mumble rap”, distinct for its ad-lib-heavy rapping, little emphasis on lyrical quality and use of lo-fi beats with distorted bass. Many young artists found success through the easily accessible distribution platform Soundcloud, earning big contracts from major record labels following their digital success. Some of their careers have stagnated but names such as Lil Pump, Lil Xan, Trippie Redd and Playboi Carti still float about in the zeitgeist. Some of them, such as Juice WRLD, XXXTentacion and Lil Peep, unfortunately, saw an early death.

The rise and decline of SoundCloud rap is the focus of this documentary by Justin Staple, who previously produced the Viceland series The Therapist, which revolved around musicians sitting down to discuss their lives in a therapy setting. His clout in the audiovisual field lets him reign in some of the well-known Soundcloud rap stars including Lil Xan, Smokepurpp and Bhad Bhabie, who sit down to discuss their music, their lifestyles, their coming-of-age, and that of their peers.

Shockingly, despite being the least likely to display any self-awareness, the 16-year-old Bhad Bhabie – real name Danielle Bregoli – whose career was born after an appearance on Dr. Phil (the “cash me outside” girl) makes some of the more salient points, criticising the hypocrisy and exploitation in the music industry and chastising how the SoundCloud community began with a strong sense of individuality but became homogeneous when everybody started cloning each other, imitating the same taste for coloured hair, face tattoos and prescription drugs.

It might have been an interesting experiment to let Bregoli narrate the documentary but those duties go to the more historically informed New York Times music critic Jon Caramanica. As one of the first to write about the emerging wave, Caramanica is the hand the film needs to guide us through this biography of SoundCloud rap. He provides great insight, succinctly connecting the dots with punk rock to help the audience understand how new tech and the contemporary political context has created a new generation of stars, and how their non-conformist aesthetic has resonated with a new generation of Americans.

With all the joys the music has provided, though, there have been several high-profile early deaths and extremely controversial personalities, such as those of XXXTentacion and 6ix9ine, both of whom would be fascinating subjects for solo documentaries. With good access, great footage of rowdy concerts and a solid talking head at the centre, Justin Staple has made a cinematic bible for this intense but short-lived hip-hop movement.

But whilst American Rapstar provides a good understanding of the big picture, it’s also one of those films where an individual portrait would be more compelling than the panorama. In fact, one such doc is out there – Lil Peep biopic Everybody’s Everything, which dissects the artist by putting his youth, family and friends under a microscope.

Sunless Shadows (Mehrdad Oskouei)

Like Songs of Repression, Sunless Shadows is significant for the filmmaker’s ability to create the time, space and mutual trust with his subjects to get their best contributions around a difficult, sensitive topic.

Docmaker Mehrdad Oskouei has been down this road before, chronicling the stories of jailed Iranian women. His previous feature Starless Dreams brought him into the imprisoned world of women who had committed robbery or dealt drugs and in Sunless Shadows he returns to this territory with a refreshed focus and a profound narrative element. This is a very poignant portrait of adolescent girls who are serving time at a juvenile detention centre for the murder of a male family member.

Honing in on the dialogue around patriarchy, Oskouei prefers not to get to know the cohort of girls in a conventional manner – their hopes, fears, dreams, etc. – at least not on camera. Instead, he cuts straight to the issues at heart and talks to them about the details of the crime, the legal process, and their feelings on the environment they’re locked in.

They’re very frank in detailing the actions of their husbands or fathers and how a knife or poison seemed like the only way to confront them. The majority of them could lay a claim for self-defence. Oskouei asks, how does it come to the point where you have to kill your father? His subject plainly responds, “A total lack of support from society and family.”

It’s impossible to tell how long the filmmaker spent at this facility to gain such openness and honesty from his subjects but the girls affectionately refer to him as Uncle Mehrdad, so the level of trust is self-evident. Three of the girls are particularly interesting cases because they killed their fathers with their mothers, who are now on death row, and thus their interviews revolve around the worries on mortality in relation to the parent-child dynamic. How long will they be able to see each other for?

Oskouei’s immersion catches great actuality, especially an intense discussion between the girls on toxic marriages and gender roles, referencing society at large. “The moral? Never let family members force you to marry”, summarises one of the girls directly to the camera.

Another one, who was freed whilst her mother still sits on death row, goes further with the sociopolitical subtext by stating that she enjoyed her years locked here with this community of girls more than her life outside. You hear a few testimonies stating how the years in the detention centre, free from Iran’s patriarchal attitudes, have been the best in their lives.

Sunless Shadows is such a brilliant documentary because it treats the subject matter with the gravitas it needs. To accomplish this, Oskouei uses an intimate observational lens and his excellent relationship with the subjects to encourage their best talking heads and takes it a step further by employing a powerful confessional element. Throughout the film, the girls are encouraged to go into a room with a single camera and record a message for any family member of their choice – including the late male ones – for as long as they would like to speak.

Some viewers may never be able to ignore that these girls are in for murder but it’s impossible to listen to their plights and not be moved. In this prison movie, social reform is more urgent than personal reform.

Check out the trailer for Caught In The Net below and stay tuned for more coverage of CPH:DOX 2020, including a look at Barbara Kopple’s new film Desert One and the award-winning We Hold The Line, which follows Filipino journalists under the threat of Rodrigo Duterte’s government.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Musanna Ahmed is a freelance film critic writing for Film Inquiry, The Movie Waffler and The Upcoming. His taste in film knows no boundaries.