I remember walking into the living room one day around Christmas time, my sister was sat on the sofa playing video games. One character, in particular, caught my eye. She stood out because she was wearing a bikini top and ripped trousers next to several men dressed for heavy combat. My sister told me that her name was Quiet, she couldn’t speak.

Probably guessing that I was going to question the costume design for this character she told me that the reason was “she breathes through her skin.” Now, although this is a video game which is a whole other ball game in terms of discussing sexism in character design, this is something prevalent in the films we watch at the cinema, mostly action/adventure films.

What is a “Strong Female Character”?

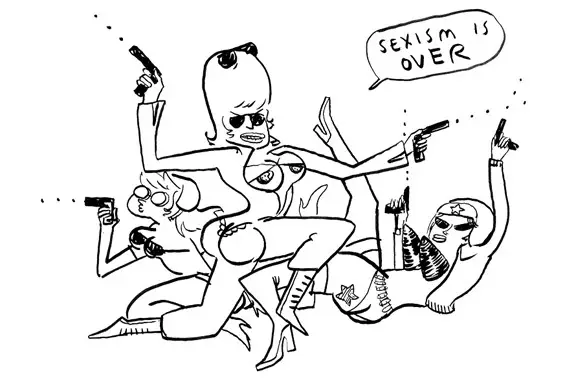

A term that is tossed around a lot in terms of the women in these films is that they are a “strong female character” But what does this mean? What is not my definition of a strong female character is throwing together an overly sexualised outfit for a female actress and giving her a gun and some one-liners and then declaring that “sexism is over”. It’s such a broad term, in fact, that it’s thrown around constantly in film reviews when a female character appears to have her own mind.

It’s often said that the representation of women on-screen is far better than it used to be. We have seen recent films such as Mad Max: Fury Road depict women as equals, strong and capable without the need to sexualise them or degrade them in any way. The titular character becomes secondary to Charlize Theron’s fierce Furiosa and her mission to protect the women she has saved from the villain in the film.

Similarly, in Star Wars: The Force Awakens no female characters are subjected to impractical or sexualised costumes. Daisy Ridley’s character Rey’s costume is fully designed with functionality in mind. The tan-colour lets her blend into the desert surroundings, the design of her trousers and boots that make her look like a capable character who isn’t restricted by unnecessarily tight clothing.

The belt, the one thing that adds a “feminine” curved shape to the outfit is also practical and is used by the character at points in the film. Everything the character does in the film – fighting, running, jumping – is more than believable due to the design of her clothing.

Sexual Empowerment vs Sex Appeal

But this is where it gets confusing. There has been a surge in female superheroes on our screens in the past few years from Halle Berry’s portrayal of Catwoman, to more recently, Scarlett Johansen’s portrayal of Black Widow across the Marvel cinematic universe, such as in Iron Man 2 and The Avengers , and while that’s great, it wrongly suggests that the representation of women on screen in these genres is no longer an issue.

Often, women appear to be empowered: they are the protagonist or antagonist, carry great strength and dialogue. However, although the actress appears to be acting on her own terms, i.e. owning her sexuality, in reality, her movements, particularly while fighting, are sexualised, and the camera will pan up and down her body, focusing on aspects of her tight fitting or revealing costume that are pleasing to the heterosexual male viewer.

It caters to the male gaze; a term coined by Laura Mulvey in her 1973 essay titled “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, in which she explains that in film, women are typically the objects, of gaze rather than the possessors of it. This is due to both the choice of the typically male filmmaker and the assumption of heterosexual men as the default target audience for most film genres.

This concept, when applied to these action/adventure characters was summed up by Caroline Heldman in the documentary Miss Representation, in which she explains “When you peel back a layer or two you discover it’s not really about their agency, I call this archetype the fighting f*ck toy because although she is doing things supposedly on her own terms she very much is objectified and exists for the male viewer”.

This takes away much of the appeal of these characters because when you build a character on the basis of appearance and sex appeal there is little left for the audience to empathise, creating a dynamic in which the audience objectifies rather than sees this character as a human.

Looking to the Future

The most recent example of ridiculous costume for a woman in an action/adventure film, a promotional image released from the upcoming Jumanji, in which actress Karen Gillian stands in tight, skimpy clothes inappropriate for her surroundings with three fully clothed men (much like Wonder Woman with the rest of the Justice League at the top of this article). After backlash to the image, she took to Twitter to say “Yes I’m wearing child-sized clothes and YES there is a reason! The payoff is worth it, I promise!”

However, I’m not so convinced, it’s likely another “She Breathes Through Her Skin” or “She Owns Her Sexuality” style excuse but time will tell on this occasion. The main problem with these costumes on these women in these films is that it sells an idea of what a strong female character is whilst also selling her short. Giving less to character development and less to showcasing an actresses performance in order to focus on looks and sexual appeal.

Because at the end of the day, when I see a film, I don’t want to see a strong female character. I want to see a human character. Someone who is multifaceted and relatable whilst also able to hold her own in an action/adventure story and due to costume choices and choices made by the directors of these characters are being sold short and I believe they can do better.

What do you think about the promotional image released for Jumanji?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.