COSMOS: POSSIBLE WORLDS (S3E5) “The Cosmic Connectome”: How The Universe May Come To Know Itself

Digital Media Program Coordinator and Professor at Southern Utah University…

“The universe is a pretty big place. If it’s just us, seems like an awful waste of space.” – Carl Sagan

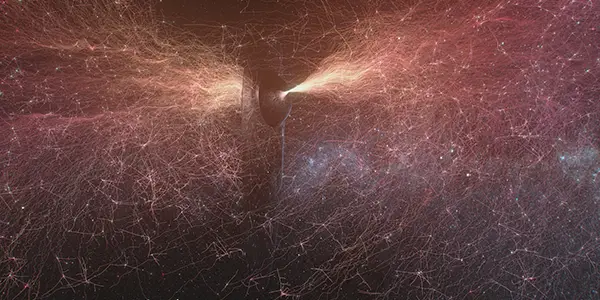

Carl Sagan once pointed to our ability to comprehend the vastness of the universe, and, at least by some small measure, the incredible diversity of “starstuff” throughout, and eloquently referred to that cognitive understanding as “a way for the universe to know itself.” We are, after all, made from the very same “starstuff” that we are slowly coming to understand. In the fifth episode of Cosmos: Possible Worlds, we explore our greatest asset in the journey toward knowing the universe, the vastly complex and intricate galaxy within each of us, our individual “cosmic connectome”: the mind.

Episode Summary

For thousands of years, we have been working to understand the complex secrets of the mind. Paradoxically, epilepsy, a disease caused by a malfunction in the brain, provided the means by which we would ultimately come to understand the organ as much as we do. Rather than aligning himself with the popular view of the time, that epileptic seizures were some kind of punishment from harsh gods, Hippocrates, the Father of Medicine, insisted: “nothing happens without a natural cause.”

Over the next few millennia, many of the mind’s mysteries were unlocked, step by step, by various pioneers in the field of neuroscience. Today, we’ve come to define this critical tipping point between mere consciousness and radical self-awareness, that moment when the “spark of life,” whatever it may be, creates not only life, but true understanding, as “emergence.”

Experiments in Connecting Reality

If the mission of Cosmos, and the endeavor of science at large, could be illustrated in a few brief words, we could do far worse than something like: “Connecting the truth of reality with how we experience it.” To that end, Cosmos continues to experiment with compelling ways to connect the truth with our experience of reality.

With Vavilov, the last episode, the choice to employ stop-motion was a brilliant stroke in the fulfillment of this endeavor. In this episode, another technique was used that bridged the gap between our present experience and a significant moment in scientific history. In the 19th century, at the Manicomio di Collegno, a psychiatric hospital in Turin, Italy, now long abandoned, physiologist Angelo Mosso invented new ways to measure activity in the brain.

Among these many experiments was a perfectly balanced table, on which volunteers would lie and engage in cognitive challenges. He theorized (correctly) that blood would rush to the brain when the subject was engaged in deep thought, and that the harder the brain was working, the more blood would be needed. By simply measuring the tilt of the table, he could measure brain activity. One of his greatest breakthroughs, however, occurred as he measured a young epileptic patient in a deep sleep. Host Neil deGrasse Tyson explains: “On that snowy night, Angelo Mosso gave the brain its first pen to write with. He had invented neuroimaging.”

To depict this incredible breakthrough, the team behind Cosmos used real images of the hospital as it stands today in Turin, with dilapidated furniture, broken windows, and crumbling walls, and projected ghostly, transparent apparitions of the people and equipment that were in the room on that fateful night. This literal “blending” of tangible, contemporary reality with the dramatized images of history put Cosmos’ compelling ability to fulfill the lofty goal of connecting the truth with our reality fully on display.

Advocating for Secular Thought

Throughout history, great men and women have gifted to mankind incredible strides in scientific thought. Still, for all their amazing ability to think ahead of their time, these people were still just as susceptible to whatever prejudices were prevalent in their contemporary societies. An example depicted in the episode is the French physician Paul Broca. He discovered which area of the brain is responsible for speech (now referred to as “Broca’s area), and was a progressive in many ways, but prejudiced in many others. Regarding our historically conventional tendency toward prejudicial thought, Tyson says:

“His falling short of humanist ideals shows that even someone as committed to the free pursuit of knowledge as Broca could still be deceived by endemic bigotry. Society corrupts the best of us. It’s a little unfair, I think, to criticize a person for not sharing the enlightenment of a later age, but it is also profoundly saddening that such prejudices were so pervasive. The question raises nagging uncertainties about which of the assumptions of our own age will be considered unforgiveable by the next.”

The message of Cosmos, however, is that these prejudices can easily become a thing of the past, if we would simply shed false illusions, and step into the light. As Carl Sagan himself profoundly said in the first episode of the original Cosmos series:

“Science is generated by and devoted to free inquiry. The idea that any hypothesis, no matter how strange, deserves to be considered on its merits. The suppression of uncomfortable ideas may be common in religion and politics, but it is not the path to knowledge. It has no place in the endeavor of science.”

These prejudices were (and still are) a by-product of the prevalence given throughout our history to myth and unsubstantiated religious claims. Indeed, “pattern recognition” is the greatest factor behind the perpetuation of religion to this day. Tyson refers to pattern recognition as one of humanity’s greatest strengths and greatest weaknesses. False pattern recognition is borne of “the confusion of correlation with causation and the wishful thinking that prevails when people feel powerless.” Speaking specifically of working to find cures for a child suffering from epilepsy, his words can easily be applied to society’s striving for any advancement: “As long as we search for it in the whim of the gods, we had no hope of helping him, or ourselves.”

Imagine, therefore, if we gave secular scientific thought the same precedence we currently allow for religion, or capitalism, or indeed, any number of society’s backward priorities. Prejudice would have no place in a scientifically-minded society, simply because the prejudicial thought would have to be proven before it would be allowed to take hold. In addition, we’d be far more advanced in every way, and neither climate change nor COVID-19 would be pressing upon us now. By giving sway to the “whim of the gods” (religious and capitalist gods, among others) we’ve allowed prejudice, greed, and destructive processes to take hold, and threaten our very existence. How backward we are!

And yet, “for all our failings,” as Sagan says, we are still “capable of greatness.” The key, of course, is for all of us as a society to grow up. Even in Christian scripture, we find a powerful endorsement for leaving behind the childishness of mankind’s early religious thought: “When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.” (1 Corinthians 13:11) Why not “put away childish things” now, as a society?

Conclusion

Tyson explains the key to our collective ability to “put away childish things,” what we must do for our species’ “emergence” to overcome antiquated regressive ideas, in order that we may one day know the universe:

“This is the essence of emergence: tiny units of matter operating collectively to become something much more than themselves, to enable the cosmos to know itself. But there is a vision of emergence that takes it even higher. Can we know the universe, and will it ever come to know us?”

With Cosmos, Carl Sagan and the team that carries on his legacy stand as a beacon for the truth, a powerful light in the darkness. How do we leave the darkness behind? Simple: turn toward the light.

Cosmos: Possible Worlds Season 3 Episode 5: The Cosmic Connectome, aired on March 23, 2020 on National Geographic.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Digital Media Program Coordinator and Professor at Southern Utah University and Southwest Technical College; M.Ed.; Author at Labyrinth Learning and Film Inquiry. Passionate educator of film theory and history. World-class nerd with a wide array of interests and a deep love for many different fandoms.