THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES: A Film That Found Beauty Everywhere

Ben is a former student of cognitive science who is…

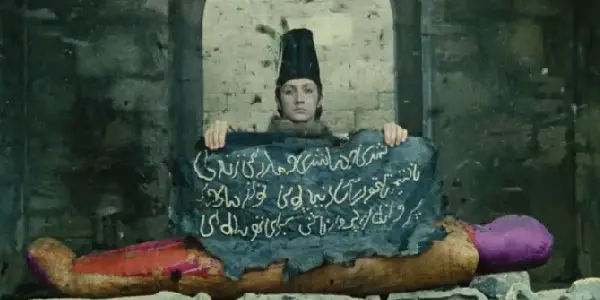

Sergei Parajanov‘s 1969 experimental film The Color of Pomegranates, follows the life of the multilingual 18th-century poet Sayat-Nova, but it opens with a disclaimer: it is not concerned with teaching us about the poet’s life, but rather giving us a perspective on how Sayat-Nova personally experienced the world. As such, the characters and events are not explicitly named; instead, we get sequences and compositions suggesting themes. We can sense love, death, faith and other aspects of human life at various points in the film but The Color of Pomegranates does not tell us what specific person or circumstance we might associate them with. The film consists of a series of tableaux, of static and orderly compositions, and the actors don’t act so much as perform interpretive dance.

That said, there is much to understand in the film that won’t be straightforward to viewers who don’t have background knowledge about its subject matter. The clothing, customs, and decor it uses are drawn from Armenian culture, and the film’s settings and plot (insofar as it has any plot) are drawn from the historical record of Sayat-Nova. Also, some facts about Sayat-Nova‘s life aren’t depicted in the film at all, but still may hold a strong influence on how a viewer receives the film.

For example: the film depicts Sayat-Nova‘s death but does not tell us anything about how he died. His death is conveyed only by the actor portraying him (Gorgi Gegechkori) lying down on the floor. In reality, Sayat-Nova was beheaded for his refusal to abandon the Armenian Church. Knowing this, and inferring Sayat-Nova‘s religious devotion and acceptance of death, illuminates the film.

In The Color of Pomegranates, everything from major life events to mundane activities are made to look like tapestries or religious icons. It finds beauty everywhere in the world, and its way of bringing out that beauty is through a particular kind of abstract representation and spiritual reverence; though, at the same time, it depicts death and recites poetry about suffering. This is the world as seen by someone like this film’s conception of Sayat-Nova: someone who lives an ascetic, pious life and ultimately accepted execution, but still maintained a great mind for romanticism.

The World as a Window

In the film’s opening shots, we see pomegranates laid on a sheet of white fabric; their juice stains it red – hence, The Color of Pomegranates. Shortly after that, we see a knife lying on the red stain – now it’s the color of blood. The entire film works like this. It shows us objects and people carefully arranged in suggestive ways, though they don’t always suggest anything as straightforward as a knife laid on a red stain. But even when it’s hard to parse what the images before us mean, we understand them as symbolic.

Sayat-Nova encounters death at a few points points in The Color of Pomegranates. The first time is probably the most captivating: after an especially lavish sequence of tableaux, we see the inside of a tomb. A body wrapped in a multicolored shroud lies there, and a powerful gust of wind fills the air with debris. This is one of the few moments in the film that feel chaotic, as though the organizing principles governing the rest of the film’s imagery was, for a moment, broken through.

Later on, Sayat-Nova is present at a funeral. A pair of angels guide a blindfolded man into the scene, take a rolled-up flatbread from him, and offer it to Sayat-Nova. A voice sings that Sayat-Nova has known suffering “beyond measure”, and the funeral attendees chant: “The world is a window”.

A window to what? Presumably, a window to God, to a spiritual realm more perfect and more justified than the world we live in. But the nature of what lies beyond the window is not what is impressive in The Color of Pomegranates. What is impressive is Sayat-Nova‘s ability to see through the window, and the film’s effort to let us see through his eyes – to look upon suffering “beyond measure” and see something better and purer behind it.

At various points in the film, characters are depicted holding flatbread, pouring a mound of dirt on it from a bowl, and then folding the flatbread over the dirt. Indeed, we see the blindfolded man perform this ritual shortly before he brings the flatbread to Sayat-Nova at the funeral. Late in the film, an inter-title says: “The bread you gave me was beautiful, but the earth more beautiful still. I shall return to the earth.”

The experience The Color of Pomegranates tries to evoke is one of seeing the world in a way that can reconcile the bread and the earth, the pomegranates and the knife. In some of Sayat-Nova‘s poetry (though mainly not that used in the film), you can find lavish comparisons and grandiose personal truths articulated in ways that are hardly religious. But this film seems to have ritualistic order: its uses symbols and strict design in a way that suggests reverence for something unseen. Each scene resembles a religious icon or tapestry, even when depicting something mundane. The beauty expressed in Sayat-Nova‘s poems is worldly beauty: it’s wonderful, but easily lost, and it stands in opposition to suffering. This film’s Sayat-Nova sees such beauty as a window to something beyond suffering.

Reverence of Memory

But there’s a layer to some of the imagery in The Color of Pomegranates other than its solemnity. There are scenes that bring back imagery from earlier in the film, from different points of Sayat-Nova‘s life; there are also actors recurring in multiple roles, and even shots that are repeated twice.

We may, in part, take this to evoke Sayat-Nova‘s experience of calling on his memories to understand his present life and formulate new representations of beauty. But there may be more than that to the apparent significance of memory.

There’s an interesting trend in how film critics and other figures have discussed this film. They say it feels ancient, as if the viewer were watching something made centuries ago. This is only natural, considering that it strives not to give us history, but to give us the experience of a historical figure. Melkon Alekyan, Sofiko Chiaureli, Vilen Galstyan, and Gogi Gegechkori play Sayat-Nova as a pensive figure, regarding the events he witnesses with the same careful wonder that an engaged viewer has when parsing this film’s unusual visual language.

So, even though the film is no clear exposition of history, it does inspire a sort of reverence for something we can recognize as historical. It’s no wonder, then, that some view The Color of Pomegranates as a display of the resilience of Armenian culture in the face of violence done against Armenian people.

The Color of Pomegranates: Battle without Hatred

Aesthetically, there is perhaps no film like The Color of Pomegranates. The sensations it offers and the symbolism it constructs are both extensive, but it thrives on even more than that: it thrives on the notion of symbolic importance itself, the idea that we’re looking at speaks to something significant, even if we can’t tell exactly what that is.

It will probably be impenetrable for some people, or insufficiently entertaining. But for those receptive to it, The Color of Pomegranates offers an experience of careful, questioning celebration that combines appreciation of artistic beauty with cognizance of worldly suffering. One may approach it as an achievement of creativity, as an historical film, as a religious film, or even as a political film; in any case, it’s rich cinematic ground for those who wish to explore unconventional art. The extras available with the Criterion edition discuss many of the film’s different angles, and they include a documentary by Mikhail Vartanov, a friend of Sergei Parajanov and a great commentator on his work.

What aspects of The Color of Pomegranates stand out to you the most? Tell us your thoughts in the comments below!

The Color of Pomegranates is available on Criterion.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Ben is a former student of cognitive science who is currently trying to improve his writing style and ability to understand and appreciate films containing unfamiliar perspectives. He tries not to hold films to a strict set of criteria, but does believe that strong movies can change your outlook on the world. His favorite films include Whisper of the Heart, Hellzapoppin', Foolish Wives, 42nd Street, and the work of Charlie Chaplin.