The Reemergence Of Charlie Chaplin Through Cosmo Kramer

Jack is a recent MA Graduate from the film department…

Seinfeld is, and consistently was throughout its run, a comedy of words and ideas. Often labelled “a show about nothing”, it would actually be more accurate to call it a show about everything, about the little moments and stupid details of life that can build and build into moments of comedy. The show’s characters barely change throughout its nine seasons and, season four aside, ‘nothing’ really happens in their lives – but each day for them seems a cavalcade of bizarre, just-about-believable situations that escalate rapidly over the course of 25 minutes, often to be forgotten entirely by the next installment.

It is in its script, and the delivery of said script, that Seinfeld shines so bright; even on repeated viewings the show is funny simply in anticipation of lines being delivered. It is a show that is high on its own writing, infectious in its laughter, even when the characters portrayed are barely doing anything at all.

And often when that happens, there is a bang of the door, a skid of shoes on the floor, and Cosmo Kramer has entered the scene.

Cosmo Kramer

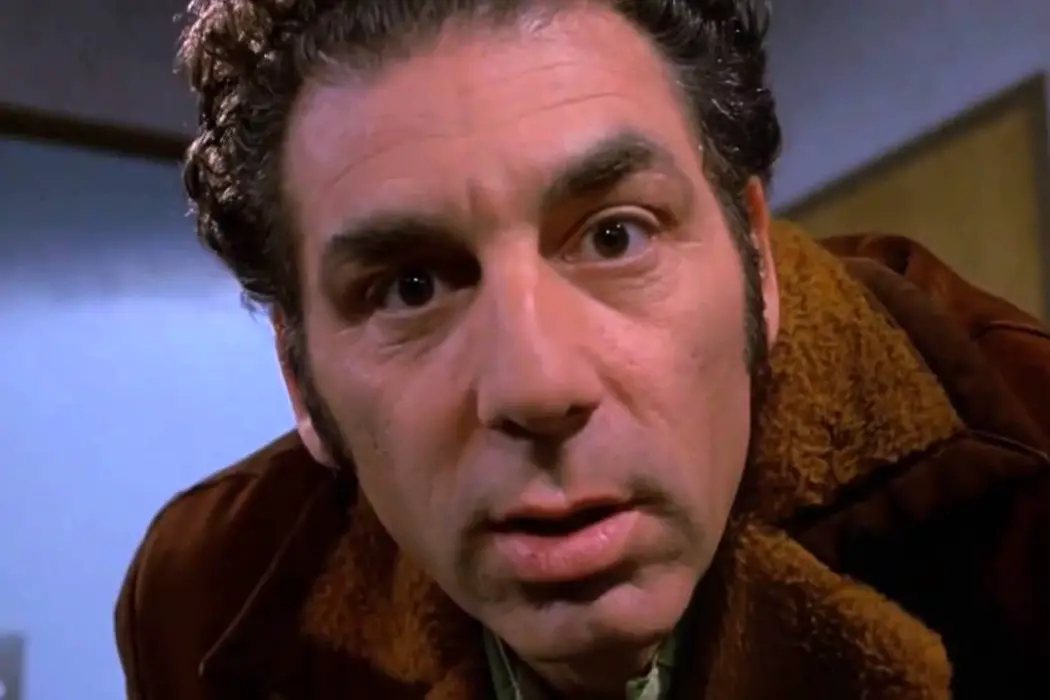

Kramer, played by Michael Richards, is a burst of lightning that would be just as much at home in a silent 1920s comedy as he is in a smash-hit NBC show. For every character in the show, we laugh at what they are saying, or how they deliver a line, or in anticipation of what situation they’ll find themselves next. With Kramer, he is funny simply by existing, simply by entering a room; Richards has a remarkable gift of physical presence that eclipses everybody else on the show (although it must be noted that Jason Alexander, playing George, is underrated as a physical comedy actor). Kramer is the comedy relief on a comedy show, the character to turn to when the words aren’t quite as sharp as usual, when the actors don’t quite believing in the story they’re telling – Richards, with all of his twitches, mannerisms, is the ultimate quirk on a show that was pretending to be about real life.

Most importantly of all, he is funny, deeply funny, funny to the point where he seemed to reinvent the art of falling over and getting back up in comedy. It is almost revolutionary in its simplicity, a bizarre, consistent sub-plot on this comedy that leans so heavily on its script and the delivery of its words; three characters get on with their lives, while occasionally, a cartoon character joins in on the drama.

There is no necessity for Richards to have played Kramer in this way – if we look back at similar physical actors, of early cinema, early comedy, their instinctual means to use their body as a vehicle for laughter was borne out of a lack of choice. Keaton, Chaplin: these were physical actors who turned their bodies into a new form of art because, in a verbal sense at least, jokes were not an option. Richards was not under this constraint and, as already noted, Seinfeld was a show that above all else was revolutionary and indeed, hysterical, because of its script, what each character said and how they said it. Kramer was often funny through the verbal but it is the choice of Richards to create a character that, as well as interacted with the other characters through language, but also interacted with the environment, the scenery, in a way that opened up the entire scene – the whole world was a prop and Kramer was dedicated to using it.

In this physical sense, the comparisons between Richards and Chaplin are impossible to ignore.

Charlie Chaplin

Charlie Chaplin was so many things throughout his career; a revolutionary stage-performer, a pioneer of the art of falling over and looking totally silly. An amazing director of both the comedic and, in something like A Woman of Paris, the dramatic and the romantic. Late career he made the anti-fascist film The Great Dictator, which turns its attentions to words rather than actions, and, in his last great picture, Limelight, an autobiographical film that seems to dissect his life and self on screen in tragic ruthlessness. Later releases of some of Chaplin’s most famous works have, remarkably, new musical scores and cues that were written by Chaplin himself – a final late flourish of yet another talent of this auteur.

These achievements and talents do not necessarily have much of bearing of Chaplin’s influence on the character of Kramer, but they do well to highlight how much of Chaplin’s career is forgotten in the face of his enviable and unforgettable talent in front of the camera. Chaplin used his body as a means to communicate when there were no spoken words in the cinema – a title-card is fine for exhibiting speech, but lacks the timing and the tone of a real punchline. Instead, Chaplin’s body was his first and final joke – he made the process of dusting off a shoe, or walking from one room to another, or simply sliding up to a woman in order to win her affections, incredibly funny. The character of ‘The Tramp’, Chaplin’s early signature persona, never switches off his ability to make the audience laugh – even when expressing passivity, or when he is not the focus of the camera, he is always there, always doing something.

In The Kid, Chaplin’s young son is being examined by the doctor. The boy is the centre of the frame, with the doctor to his left and Chaplin to his right. The boy and the doctor are the important characters in this frame; one is being examined while the other is doing the examining, and the audience should be eager to know what the outcome will be. Yet, to the boy’s right, is Chaplin, stealing the show, whether that be through traditional jokes (he says ‘ah’ when instructed instead of the boy) or through less traditional, more interesting means, like at one point giving the audience a knowing look, almost saying through the camera “is this guy a real doctor?”. Chaplin the character demanded the attention of his audience, even when he shouldn’t have, and this is the same skill that is embodied so similarly in Michael Richards and in Kramer.

Modern Reemergence

Kramer, unlike the glory years of Chaplin, had the power of language at his disposal, the ability to deliver lines and interact more naturally with the characters surrounding him. Crucially, however, Richards didn’t need this; Kramer would succeed in black and white, would have succeeded with just the occasional title-card. His body is his comedy vehicle and something as simple as opening a door is turned into a catchphrase, much to the delight of the audience. Kramer’s body exists outside of the space that all of the other characters employ – he often trips over nothing and is consistently demonstrating an inability to control his own body. A character touches him, he jumps ten feet into the air in shock. Sandwiches disintegrate in his hands. In one memorable skit, Kramer fails to get a seat on the subway and practically falls into the laps of every passenger in unison as he tries. His body is a tangle, a mess, of comedic potential.

And even when Kramer and Richards are irrepressible in their delivery of a punchline or a gag, their physical comedy still shines, coming to the forefront or retreating to the background at will. In a scene where Kramer pretends to be a detective at a bar, interviewing somebody he and Seinfeld are convinced of doing cocaine, Richards delivers his lines with perfect timing – the comedy of the scene oozes out of Kramer’s bizarre dialogue with this straight-man counterpart. Yet the script, however hilarious and driving it is for the scene, is again overshadowed by Richards, and Richards‘ commitment to the body as a comedic vehicle: a stunt where Kramer drinks an entire pint of beer in one go, while simultaneously smoking a cigarette, should be the stuff of comedy legend.

Perhaps it is Kramer, in his insistence to be away from the real, that lends the show’s darker moments their reprieve. In the later seasons especially, Seinfeld has a smattering of incredibly dark moments, including the killing of George’s wife, Susan, through a freak envelope-licking accident. George is told of his wife’s death and, not only is he seemingly indifferent to this tragedy, but so are the rest of the cast. It may be Kramer that prepares the audience for these moments – it is such an alien notion, their indifference, that it only becomes possible to be funny by introducing a semblance of fiction, of fakery, to the show from the very beginning. Chaplin was known for his films often balancing the absurd and the comedic with more tender, heartfelt narratives – Kramer’s physical style ultimately preparing the audience for a shocking reveal, a cruel reveal that in turn becomes funny, is an unexpected evolution of the archetype.

Conclusion

Again, we return to necessity. Chaplin was funny through his body because he had to be, and even when he introduced the power of spoken speech into his work, the physical comedy remained – instinctual, impossible to remove. In the best possible way, Kramer feels like a character out of place and out of time – he exists as the reminder of the fake, of the cartoon. Where every character at least has the illusion of being a real person, living a real life, Kramer is the sore thumb of the animated poking through the real, splashing everything he touches with the colourful hues of the silly.

Just like Chaplin, the joy of the character of Kramer is seeing another kind of creature, one created through the lens of the absurd, interacting with the world as we know it, and seeing the out-of-control, spiraling outcomes – when Michael Richards comes on screen, the world of Seinfeld suddenly seems to drain into black and white.

What do you think? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Jack is a recent MA Graduate from the film department at the University of Southampton. He has been writing about film and football casually since 2013, considering himself as an expert on the works of Akira Kurosawa, Park Chan-wook and Steve McQueen ; less of an expert on every other important director.